Introduction

The historic Brexit referendum of 2016, in which the UK voted to leave the European Union, initiated a complex web of political and economic forces that have reshaped the nation’s financial landscape. Nearly four years elapsed between the pivotal referendum in June 2016, where 51.89% of the population voted to depart from the EU, and the official separation of the UK from the European Union. Negotiations between the UK and EU began a year later in June 2017, and formally ended with the EU-UK withdrawal agreement in November of 2018. The UK officially left the EU on the 31st of January 2020, with a transition period lasting until the 31st of December 2020. The two sides reached a consensus on their future relationship in December of 2020 with the UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, a free-trade agreement allowing goods to be sold between the two without tariffs or quotas. These new rules took effect on the 1st of January 2021.

Despite deals being reached with the EU after extensive back and forth debate, as outlined above, many questions remain on how Brexit will affect the UK’s economy and financial sector. The slowdown in the UK economy and uncertainty caused by Brexit are responsible for a fall in UK businesses’ valuations, which have made these companies particularly interesting for US Private Equity (PE) funds. In fact, the total value of UK take-private deals increased from £4bn to over £29bn between 2020 and 2021. Some examples of such deals, that we’ll mention in this article, include the buyouts of Worldpay, Morrisons, and Biffa. But this trend has raised concerns about foreign buyouts of important UK companies and assets, particularly in the defence sector. As for the UK-based private equity firms, they have experienced regulatory and operating challenges due to Brexit. However, the UK PE market may benefit from the additional flexibility the country now has in policy making.

BSIC previously touched on the theme of undervalued assets in the UK in our article “An Update on the Private Equity Industry” published in March of this year (here). However, in this article we aim to provide a more comprehensive examination on the reasons behind American PE firms acquiring UK companies, and give an overview of the UK PE market.

Brexit’s Impact on Valuations

A Morgan Stanley analysis published in July of this year found that UK core plc assets, namely equities and corporate bonds, “are arguably the cheapest asset class in the world.” So how could Brexit have led to depressed UK valuations? The answer isn’t all that clear, and Brexit alone cannot explain why London-listed indices are falling behind. Over the past 5-10 years the main driver behind the UK’s low valuations is the poor investor sentiment surrounding the broader UK macroeconomic setting. Naturally, this encompasses the macroeconomic effects and uncertainty stemming from Brexit.

Source: Financial Times, FactSet

The FTSE 100 is an index comprising the 100 companies listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) with the highest market capitalization, and helps to illustrate the general valuation of UK companies. The 2016 referendum, which resulted in the decision to leave the European Union, pushed down the value of the FTSE 100 into a discounted range when compared to global stocks. This left UK companies looking relatively cheap when compared to the US and EU. This is especially apparent when looking at the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio for the FTSE 350 compared to Stoxx Europe and the S&P. As of September 2023, the P/E of the FTSE 100 index is 9.4x compared to the S&P 500’s 25.2x.

Since 2016 most economists have held the view that the decision to leave the union will continue to harm the UK economy, but there remains significant uncertainty about the degree of damage it will inflict. Economic growth is currently expected to be lower by 4-6% over the next 15 years and trade is expected to fall by around 15%. Immigration was a defining issue in the 2016 referendum. The subsequent decline in immigration to the UK following Brexit has had a significant impact on the country’s labour market. This led to shortages in crucial sectors such as healthcare, hospitality, and science, which, in turn, exerted pressure on wages and contributed to inflation in the UK.

The UK has experienced a relatively low level of business investment over the last 5-10 years, and a significant portion of the more recent decline can be attributed to the impacts of Brexit. According to an article by Jonathan Haskel and Josh Martin published in March, business investment is estimated to be approximately 10% lower than it would have been if the UK had voted remain. This would likely be reflected in a reduction in overall output, which Haskel and Martin estimated at a little over 1% of GDP. Businesses have remained uncertain regarding the economic outlook of the UK and are therefore more reluctant to spend on new capital, which affects valuations.

One of the most pronounced effects of Brexit on the UK economy so far has been the reintroduction of certain trade barriers between the UK and EU. The loss of favourable export and import agreements with its largest trading partner significantly hindered the country’s trade performance. A paper by Bailey, Hearne & Budd “People, places and policies beyond Brexit” found that the British EU departure had and is continuing to have a negative impact on UK goods exports, especially from manufacturing supply chains.

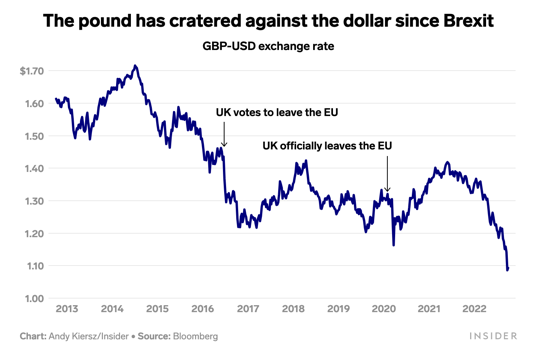

Source: Bloomberg

The weak pound may also be a major contributor to UK firms’ lower valuations, as it weighed on the country’s labour and trade markets and has contributed to rising inflation. In 2022, the pound experienced a sharp decline in value following the announcement of Prime Minister Liz Truss’ mini-budget, which included economic policies and tax cuts that received widespread criticism. The currency, however, had been experiencing a longer-term decline in value since the UK voted to leave the EU in 2016. The pound has fallen significantly against the dollar since Brexit, dropping over 15% from $1.44 on the day of the referendum to around $1.21 today. The COVID pandemic mixed with the turbulent UK political landscape with Theresa May, Boris Johnson, and Liz Truss’ premierships further fuelled the economic uncertainty and depreciation of the currency.

Amidst the backdrop of lower valuations in UK equity markets and heightened investor caution, many firms looking to raise funds are shying away from the LSE. UK chip designer ARM listed on the NYSE in September, after having been listed on the LSE for 18 years before being taken private by SoftBank Group in 2016. For many firms the diminished valuations in the UK fail to justify the expensive IPO process. Many firms are even delisting from the LSE and shifting to the US public markets. CRH, for example, an international building materials group headquartered in Ireland, moved its primary stock market listing from London to New York.

The combination of the consequences currently unfolding due to Brexit and the continued negative outlook on the UK economy has exerted downward pressure on the valuations of British corporations. This has contributed to what has been described as a “fire sale” of undervalued British companies, many taken private by foreign PE groups. It’s interesting to note that despite – and we’ll explain it in detail later in the article – growing national security concerns surrounding foreign takeovers of UK companies, Lord Gerry Grimstone, Britain’s investment minister, argued in favour of foreign investment. He claims that UK firms bought by overseas investors are more productive and create more better paid jobs.

American PE firms’s Corporate Raid on the UK

Over the past years we witnessed private equity firms around the world focusing their attention on the UK market as the uncertainty resulting from Brexit and the devaluation of the pound led to depressed valuations of UK companies. The potential gains foreign investors saw in acquiring UK undervalued firms led to increased competition and bidding takeover battles resulting in PE firms paying high premiums to acquire the UK businesses. Over 2021, UK-listed companies were taken private at an average premium of 47%, and some large bids far outstripped those levels, with US PE fund Clayton, Dubilier & Rice offering a 61% premium for the UK supermarket chain Morrisons. Brenda Rainey, MD at Bain & Co’s private equity business, confirmed that in 2021, PE funds had “over $1tn of dry powder” to invest in deals, resulting in “tremendous competition in the industry”. Interestingly, while the premiums PE firms were willing to pay may have appeared high compared to the target companies’ trading prices, the transaction price was, in many cases, lower when compared with pre-pandemic levels due to the depressed valuations that UK companies reached.

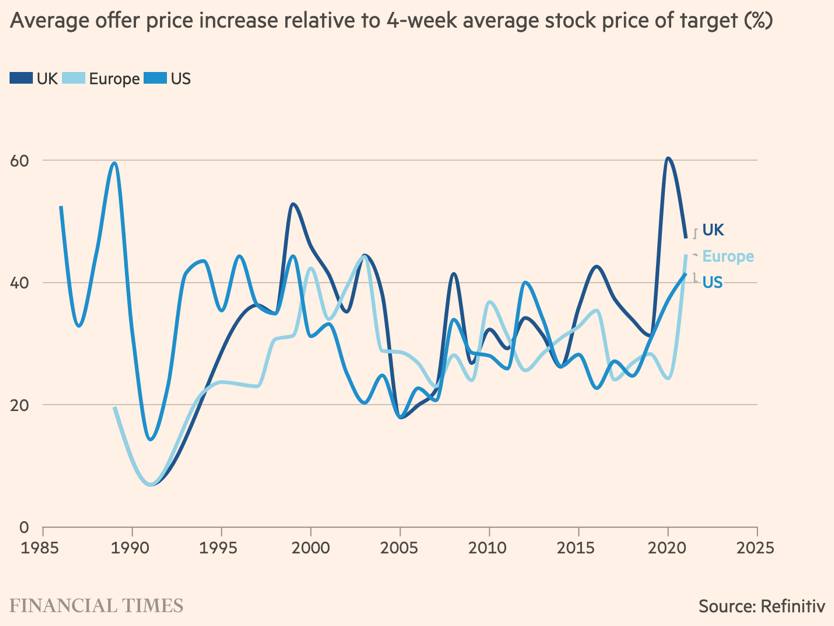

Source: Financial Times, Refinitiv

Although low valuations of UK companies attracted private investors from all over the globe, US private equity funds played the most considerable role in the UK take-private boom over the past years. Slower UK economic growth combined with uncertainty in the UK due to the Brexit referendum led to the sterling falling sharply against the dollar and the Euro, making deals more attractive for overseas buyers. Furthermore, US PE funds have been accumulating significant levels of dry power that they were looking to allocate overseas as the US market for private equity deals had become saturated.

US PE firms are particularly interested in the UK market not only because of low valuations but also because it has regulations similar to those of the US and is generally more receptive to private equity transactions compared to other European countries like Germany and France. In the UK, for example, employers have more flexibility to restructure their workforce, a common strategy undertaken by PE firms, than in other parts of Europe. Furthermore, the UK government does not have a reputation amongst investors for intervening in the commercial decisions of businesses that some other countries in the EU have.

The increased presence of foreign investors in UK businesses has, however, raised concerns primarily because some US PE funds started to focus their attention to the UK defence sector. As business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng said in 2021, “The UK is open for business, however foreign investment must not threaten” UK national security. For this reason, Advent’s acquisition of Cobham, a British aerospace manufacturing company, has raised a lot of debate over the past few years. In 2019, the UK government cleared the acquisition, agreeing with Advent on several commitments to safeguard national security and the UK economy as a whole. However, the US PE fund has been criticised over the past two years because it has divested several parts of the company, and many are worried for the ownership of UK defence technologies. Advent gained even more attention in 2021 when defence manufacturer Ultra Electronics received a takeover offer from Cobham. Many perceived the takeover as controversial as it would have handed yet more of the UK defence industry to foreign owners. The UK government investigated the deal, pressured by labour and trade unions. Steve Turner, assistant general secretary of the trade union Unite, stated that the sale of UK defence manufacturers to “overseas venture capitalists” could harm “UK’s sovereign defence capability, as well as skills and jobs”. Despite the concerns, in July 2022, the UK government cleared the acquisition. Some experts warn that the prices show signs of a bubble. One lawyer who has advised private equity groups on take-private deals paying high premiums said conditions in the markets were reminiscent of the pre-financial crisis era when buyers subsequently struggled to deliver returns on their high-priced deals. “Everyone knows people are paying a lot of money for companies,” he said. “For the model to work, every day has to be sunny, and life isn’t like that.” At the same time, nowadays, buyout groups have more ways to exit investments than in the past, including selling companies to themselves, which could help cushion the impact of any downturn.

An example of a UK take-private deal that did not go according to plan is the much-debated acquisition of UK supermarket chain Morrisons by Clayton, Dubilier & Rice, a US PE firm. CD&R’s acquisition of Morrisons had challenges from the beginning as the fund had to fight a four-month-long takeover battle against a consortium led by their rival Fortress Investment Group. Eventually, CD&R won the battle with a final bid of 287 pence per share, which was only 1 penny higher than Fortress’ bid. The PE firm paid a 61% premium on Morrisons’ closing price before the offer period began. At the acquisition announcement, experts were already concerned that Morrisons would be forced to sell assets to reduce its leverage if things went south, which is precisely what happened. With the leveraged buyout, Morrisons’ net debt almost doubled from £3.2bn to nearly £6bn. Morrisons’ new backers were caught between rising interest rates, falling property values, sticky inflation, rising wages and a falling market share. These problems were exacerbated by the supermarket industry’s thin margins and high fixed costs since high operating leverage implies that costs decrease by much less when revenues decline, resulting in a more extensive loss. As a result, in its first full year under the ownership of CD&R, Morrisons recorded a £1.5bn loss.

Recent Activity in the United Kingdom’s Private Equity market

Compared to 2021, UK PE take-private deal volumes fell, reflecting the overall slowdown in private equity deals due to the increased cost of borrowing and uncertainty regarding the global economic outlook. The challenging environment has left the PE industry sitting on a record of unspent cash, money that buyout groups are under pressure to spend. Once again, the UK market is viewed as an attractive place to “put money to work”, particularly for buyout groups that invest cash raised in dollars or euros due to the continued weakness of the pound.

In July, Chicago-based private equity firm GTCR agreed to acquire a majority stake in Worldpay, Fidelity National Information Services’ merchant payments arm. The deal values the business at $18.5bn, while FIS acquired it for about $43bn in 2019. FIS will control the remaining 45% of the company. This new separation from FIS’s primary business is expected to position Worldpay for immediate success as it combines the well-established brand of FIS with the expertise of GTCR, which has a long history of investing in the payments sector. GTCR valued the company at 9.8 times the expected fiscal 2023 adjusted EBITDA, but Jefferies analysts said the deal amount was $1.8bn lower than what they had expected. This conveys that UK companies’ valuations are still low, and foreign investors are seeing potential gains in the market. GTCR’s offer was, in fact, competing with the one from Advent International, another PE firm that was vying for the business.

Another deal announced in 2022 and completed this year is the takeover of British waste management company Biffa by US PE firm Energy Capital Partners. The deal values the company at £2.1bn, and Biffa shareholders are entitled to receive 410p in cash per ordinary share of Biffa stock they own. The private equity firm sees long-term potential in the company if injected with sustained capital investment. When the deal was announced, Biffa management said that they had recommended that shareholders accept the offer but that the latter was below a tentative bid of 445p a share submitted in June. Analysts at Citibank said that the lower offer “could be the outcome of a weak macro environment and the recent sterling devaluation,” demonstrating once again that UK company valuations are still depressed.

What about UK-based PE firms?

It’s relatively early to precisely tell the effects Brexit will have on UK-based private equity firms, because the UK’s departure from the European Union poses both significant challenges and opportunities.

Among the challenges we find the loss of passporting rights, reduced debt availability, regulatory frictions, and strong economic uncertainty. Firstly, one of the most significant consequences of Brexit for these firms is that they’ve lost their right to operate throughout the European Union without having offices in each of the member states. From now on, they’ll have to navigate through various national regulations individually. Moreover, many debt funds present in the UK are foreign-owned and may choose to leave the UK in the light of Brexit. This would make leveraged buyouts harder to finance, hence reducing PE firms’ returns. Also, English UK-based PE firms are now exposed to many regulatory frictions: compliance with EU member states’ requirements can involve regulatory reporting, disclosure requirements, and other obligations, which may result in additional administrative costs – such as having to establish EU offices or subsidiaries. On this same topic, the UK will also no longer be able to influence future laws like the Alternative Investment Funds Management Directive (AIFMD), which makes it harder for its private equity firms to access European private markets. Changes in taxation, including withholding taxes and trade agreements, may also affect the financial structuring of investments and the overall profitability of deals undertaken by these firms. We’ve already seen some funds change domicile and leave England for Luxembourg or Ireland in an effort to simplify compliance with EU regulations. Of course, portfolio companies will also be a large driver of uncertainty as they struggle to face the adverse consequences of Brexit at their own level.

On the other hand, Brexit also presents new opportunities for UK-based private equity firms. Specifically, activities in the United Kingdom are now likely to be subject to less regulation, which may create a “deregulation premium” as PE firms cut the costs of their portfolio companies. Moreover, Brexit will allow the UK to develop its own policies on the private equity industry, in which it will probably choose to favour UK based PE firms through state aid and less restrictions. For instance, this summer, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt outlined a pension reform that seeks to encourage large financial service firms to allocate at least 5 per cent of their defined contribution default fund client assets to unlisted equities by 2030.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Brexit has had profound effects on the United Kingdom’s financial landscape and its players. Since the historic referendum in 2016, the nation has experienced economic turbulence and uncertainty, which have translated into lower valuations and a depreciation of the pound. Hoping to capitalize on that, private equity firms have been snatching up English companies across many industries in take-private deals. However, this trend has raised concerns about foreign ownership of critical UK assets, particularly in sensitive sectors like defence.

Brexit has also brought regulatory and operating challenges for UK-based private equity firms, although on the upside, the UK now has more autonomy to shape its policies, potentially favouring domestic PE industry growth. In this evolving landscape, the private equity market in the UK remains dynamic, as it tries to balance the need for foreign investments with safeguarding national interests. As the global economic context continues to shift, the UK’s financial sector will continue to transform, offering both opportunities and challenges in the post-Brexit era.

0 Comments