Introduction

In the last two decades, the American skies underwent a radical transformation shaped by significant mergers. Southwest [LUV: NYSE], Delta [DAL: NYSE], United [UAL: NASDAQ] and American Airlines [AAL: NASDAQ] emerged as dominant players, holding 71.5% of the U.S. market. Contrastingly, Europe has faced a more fragmented reality. The U.S. consolidation, fuelled by deregulation and financial distress, has weathered economic downturns, leading to financial stability and higher levels of profitability compared to their European counterparts. However, Europe has begun to mirror this trend recently, with Air-France KLM [AF: EPA], Lufthansa [LHA: ETR] and International Airlines Group [IAG: LSE] all awaiting regulatory approval for acquisitions in the European market. Interestingly the market leader Ryanair [RYAAY: NASDAQ], led by their quick-witted CEO Michael O’Leary, stands out as an outlier in this landscape. O’Leary champions organic growth especially considering previous run-ins with antitrust authorities seem to have left a bitter taste in his mouth for M&A. This article will begin by mapping out the key transactions that drove consolidation in the US as well as highlighting the tailwinds that drove this activity. We will then examine the acquisitions awaiting approval in Europe and how they will change the landscape these carriers operate in before finally doing a case study on Ryanair.

The American Airline Industry: From Turbulence to Triumph

Over the past two decades the American airline industry has seen numerous high-profile mergers and acquisitions that shaped the current market for US flights. Most notable, however, were the deals that happened in the 5 years after the Great Recession. The four carriers that were most active in this period now make up the bulk of the American market. Southwest Airlines, with a current market share of 18.1%, acquired ATA Airlines’ slots at LaGuardia Airport in 2008 for $7.5mn. This allowed the airline to expand its presence in New York City. Just two years later, in 2010, Southwest purchased Air Tran Airways, getting a hold of gates at Atlanta Hartsfield Jackson Airport and the late airline’s Boeing 717 planes. The network that Southwest built from these investments later allowed for an international expansion. Delta Air Lines, with a current market share of 17.8%, purchased Northwest Airlines in a $3.1bn deal in 2008. Both of these companies were in distress at the time of the deal as they have just come out of bankruptcy. Back then, the merged entity became the world’s largest airline, however that is no longer the case. United Airlines and Continental Airlines participated in the frenzy, merging in a $3bn deal in 2010. The newly formed entity retained United’s name and Continental’s logo for combined marketing value and currently enjoys a 15.6% market share. The last modern-day giant, American Airlines, came because of another merger in 2013. As part of the deal, US Airways acquired American Airlines, maintaining the latter’s name due to brand value. It became and continues to be the largest airline globally and had a 20% US market share in the 12 months ending Q3 2023.

Looking at these past transactions and the four biggest US airlines that emerged from them and maintain their position to this day, it is noted that the market concentration of airlines in America is superior to that of those in Europe. Southwest, Delta, United and American airlines share 71.5% of the US market, whereas the biggest four in Europe – Ryanair, Lufthansa, Air France-KLM, and International Airlines Group – take up just 42.9% of total seats. As a result, the market power of US airlines allows for greater per-passenger profits. US airlines are forecast to report an average pre-tax profit of $9.53 per passenger this year, more than double the $4.36 in Europe.

The consolidation of the US airline market was the culmination of a few major factors, namely the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act, the burst of the dot-com bubble, the attacks of September 11th and the 2008 financial crisis. Since 1938, airline fares, routes and schedules were controlled by Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) that was known for its bureaucratic complacency. Airlines had to wait for extended periods before getting approval of new routes or fare changes, often never receiving a green light. The 1978 Airline Deregulation Act removed Federal control over fees, routes and entry barriers, which allowed for more competition and an expansion of the market. This prompted the creation of tens of new airlines that either consolidated or went out of business down the line. Most importantly, this drove the adoption of hub-and-spoke model first introduced by Southwest Airlines. The model paved way for higher efficiency of air transport and introduced a wider range of aircraft types that were adaptable to markets of varying sizes.

The expanding market was hit hard by a series of events starting with the burst of the dot-com bubble and the attacks of September 11, 2001, both of which led to a sharp decline in revenues. The burst of the bubble led to an economic downturn and reduced demand for business travel, whereas the attacks added to that effect through consumers’ fear and uncertainty about flying, resulting in a drop in demand for air travel. Over the following 9 years, American carriers lost $55bn and cut 160,000 jobs. Combined with the economic slowdown and reduced consumer spending following the 2008 financial crisis, airlines had to slash down capacity, with 20 firms within the industry filing for bankruptcy protection. The losses turned out to be an opportunity for some, with increased distressed M&A and consolidation activity taking place over the first 15 years of the millennium. Thus, the industry shrank from 10 major carriers to just the four discussed above – Southwest, Delta, American and United airlines.

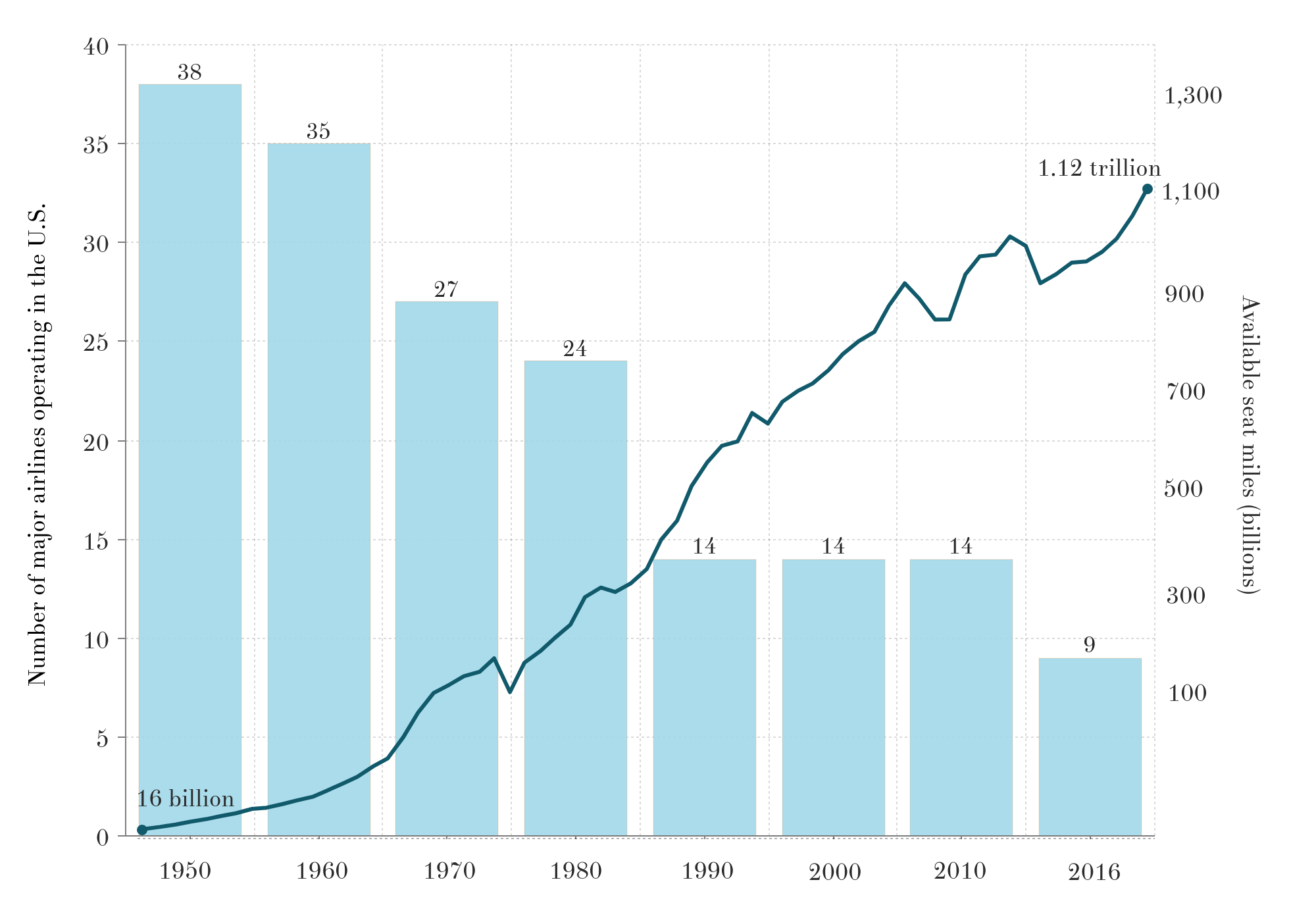

While the consolidation in US can intuitively seem detrimental to the consumers, the data and research suggest that the effect was not one-sided. Analysis by experts suggests mixed opinions on the post-consolidation airline industry. Firstly, it is evident that 40 out of 100 largest US airports are dominated by a single airline, and 93 out of 100 by one or two airlines. The control over local markets that these companies have, limit consumer choice and consequently reduce competition. After adjusting for inflation, domestic fares within the US market have climbed 5% in the 10 years after 2005 before including add-on charges such as checked luggage. Additionally, deregulation has allowed airlines to freely choose markets they fly to. The free market led airlines to sway from unprofitable rural areas to servicing major hubs and high-demand airports. Data shows that the five metro statistical areas with lowest GDP growth since 2003 saw stagnant or reduced air travel, sometimes with decreases by more than 50%. The five with highest GDP growth, on the other hand, saw air travel skyrocket from 75% to over 150%. [1] Another analysis confirms this view: small and medium hubs lost traffic, while large ones gained 15% since 2005. [2] In addition, the airline pre-pandemic EBIT margin in North America was 9.6%, twice as much as Europe’s 4.8% and higher than the global average of 5.2%. However, Figure 1 shows that in the period between 1950 and 2016, decreasing number of major airlines led to a sharp increase in available seat miles (ASM). ASM is a crucial metric of efficiency and profitability of airlines, and the major players reinvested profits to remain competitive. Eventually, it can be argued that effects of consolidation went both ways.

Figure 1. Number of major airlines operating in the U.S. and billions of available seat miles, domestic and international. (Source: ENO Center for Transportation)

However, definite certainty does come when a look is taken at the profits of these airlines. The consolidation has saved airline companies from bankruptcy, cutthroat competition and the unexpected events of 2000s. The very fragmented industry had endured $52bn in combined losses since 1977 and in the decades leading up to financial crisis. This number looks much more attractive to investors now, with a combined net income of $14.8bn in 2019 alone.

European Airlines on the Merger Runway

The European airline industry is mirroring the consolidation trend that North America experienced between 2008 and 2013. Air-France KLM, Lufthansa, and IAG are all awaiting approval for their announced acquisitions. The push for acquisitions stems from the increased capital European airline groups experienced in their balance sheets after a successful summer with bookings exceeding expectations. However, this eagerness for acquisitions has raised concerns among EU antitrust authorities, who fear a threat to competition and a lack of reinvestment of profits. Some also argue that consolidation may lead to a loss of national identity often associated with airlines.

Lufthansa’s plan to acquire a 41% share in Italy’s ITA Airways, the successor company to Alitalia, was announced in May, and CEO Carsten Spohr said he expects talks with the European Commission to wrap up in early 2024. Under an agreement with the Italian government, the German group will purchase the 41% stake for €325m, while Italy’s Ministry of Economics will inject an additional €250m into the Italian airline. Following the acquisition, ITA Airways will be integrated into the Lufthansa Group, comprising Eurowings, Swiss, Brussels Airlines, Austrian Airlines and the core German flag carrier. Lufthansa’s CEO, Carsten Spohr, cited “geography” as a key rationale behind their pursuit of a stake in ITA, as all of the group’s hubs are predominantly situated in the northern regions. The hub in Rome would fulfil Lufthansa’s need for a southern hub and offer the group additional capacity for flights as the group’s central hub in Frankfurt reached its full capacity. Lufthansa is adopting M&A strategies to emulate Southwest Airlines’ point-to-point model, which involves connecting flights directly between various cities without the need for a central hub to facilitate all connections.

A deal that has raised several concerns regarding competition in the European airline industry is the agreement reached by International Airlines Group (IAG) and Globalia, the parent company of Air Europa. The deal involves the acquisition of 80% of Air Europa by IAG for €400m. The group had acquired the other 20% of Air Europa for €100m in 2022 by exercising a convertible bond, so the total of the operation amounts to €500m for the company’s equity. IAG is betting the deal will establish Madrid as one of Europe’s premier hubs, able to rival Frankfurt, London Heathrow, Amsterdam and Paris. The acquisition would also open up new routes to Latin America and the Caribbean market, giving IAG a 26% share in the Europe-to-Latin America market, up from 19%. The deal is subject to the approval of the competition authorities and of the Sociedad Estatal de Participaciones Industriales (SEPI). The European Commission is “concerned that the proposed transaction may reduce competition in the markets for passenger air transport services” on Spanish domestic and international routes.

Furthermore, in October, the long-struggling Scandinavian airline SAS announced it expects to receive $475m in new equity and $700m in convertible debt as part of a deal involving Air France-KLM and private equity firm Castlelake. SAS will be delisted from the stock exchange with no payment to current shareholders and little to bondholders. Castlelake will become the biggest shareholder with a 32% stake and the majority owner of the convertible debt. Air France-KLM will own 20%, and the Danish government, the only Scandinavian nation still invested in the airline, will own 26%. SAS chair Carsten Dilling said securing new capital should facilitate SAS’s “emergence from the US Chapter 11 process”. Distressed M&A, as mentioned above, was a key trend in consolidating the American airline sector. Air France-KLM participating in SAS’s restructuring once again mirrors what the US market did in the past decade.

The announced deals show how legacy carriers in Europe are consolidating around three major payers: Franco-Dutch Air France-KLM, Germany’s Lufthansa, and Anglo-Spanish IAG. The three airline groups are also expected to participate in a potential bidding war to acquire Portugal’s national carrier, TAP Air Portugal. Fernando Medina, Portugal’s finance minister, stated that the cabinet approved the privatisation of the airline, currently wholly owned by the government, and that at least 51% of its shares will be sold. TAP is estimated to be worth around €1bn and reported profits last year after emerging from years of trouble that included nearing bankruptcy and a government bailout. Acquiring TAP would open up the increasingly lucrative South American market for the buyer, who would also benefit from TAP’s “privileged connections” with the Portuguese-speaking countries Brazil, Angola and Mozambique.

Ryanair and Michael O’Leary Flying Solo

Ryanair stands as an outlier amidst the consolidation trend within the airline industry as the firm, led by CEO Michael O’Leary, has firmly rejected the idea of engaging in deal-making. Instead, O’Leary has plans to focus on organic growth, implementing significant fare reductions and acquiring new aircrafts.

Although Ryanair participated in mergers and acquisitions in the past, with the acquisition of Buzz in 2003 and Lauda in 2019, O’Leary openly expressed his discontent with the two deals labelling them as “a pain in the arse.” In his perspective, acquiring other carriers is challenging from a cost point of view as it takes several years to “tidy up someone else’s mess”. CEO O’Leary has also mentioned the regulatory challenges associated with acquisition activities. Ryanair’s multiple attempts to acquire Aer Lingus faced repeated denials, primarily due to regulatory issues and concerns. The European Commission intervened twice, in 2006 and 2012, blocking Ryanair’s attempts to increase its stake in Aer Lingus on antitrust grounds, while in 2008, a cash bid of €748 million, reflecting a 28% premium, was rejected by shareholders. “Most M&A in the case of Ryanair gets blocked by the European Commission,” O’Leary said, complaining that legacy carriers have not been subject to the same barriers in their acquisitions activity.

Despite O’Leary’s aversion to mergers and acquisitions, he believes that Europe is inevitably heading toward a trajectory similar to North America. According to him, the region will see the emergence of three major high-fare connecting carriers—Air France-KLM, Lufthansa, and IAG—and one large low-cost carrier—Ryanair. He, in fact, predicts that a widening gap in costs will make Ryanair’s rivals EasyJet and Wizz takeover targets for the three high-fare carriers.

Conclusion

The transformation of the airline industry, evident in both the United States and Europe, reflects a dynamic interplay of mergers, regulatory shifts and economic challenges. In the U.S., consolidation led by Southwest, Delta, United and American Airlines resulted in an increasingly concentrated market, driving the profitability of these firms. The success narrative, however, comes with a mixed bag of effects, impacting consumer choice, airfares and regional air travel. Europe, albeit later to the consolidation game, is now attempting mergers with Air-France KLM, Lufthansa and IAG at the forefront. Concerns over competition and national identity accompany this trend and consolidation will certainly not be immune to scrutiny from antitrust authorities, especially considering the hyperactive European Commission of late. Ryanair, under CEO Michael O’Leary, defies the consolidation wave, focusing on organic growth amid regulatory hurdles. As we observe the skies of change, the industry grapples with a delicate balance between market concentration, profitability and consumer interests. The trajectories of both American and European carriers hint at a future where strategic choices will define success amidst a turbulent yet transformative air travel landscape.

0 Comments