Introduction

In a high interest rate environment, firms have to face new challenges to their capital structure and adapt to higher financing costs. Highly leveraged firms now confront more than substantial interest expenses and difficulties in refinancing. More borrowers now turn to private credit due to its additional flexibility and term certainty compared with public markets. In credit terminology, two main categories of bonds exist: investment grade (IG) or non-investment grade (high yield or junk bonds). A bond is deemed high yield if its rating is under BBB- (S&P and Fitch) or Baa3 (Moody’s). Most of these bonds trade in the US market due to higher liquidity, although there have been some developments in recent years in Europe and Asia. Today’s credit tightening particularly affects firms who’ve previously faced financing difficulties. Firms with low credit credibility, who either have structural issues or generate low cash flows, now have to bear interest of more than 8% on average on their debt (compared to less than 3% two years ago). This translates into increased aggregate US corporate default rates.

US HY bond market

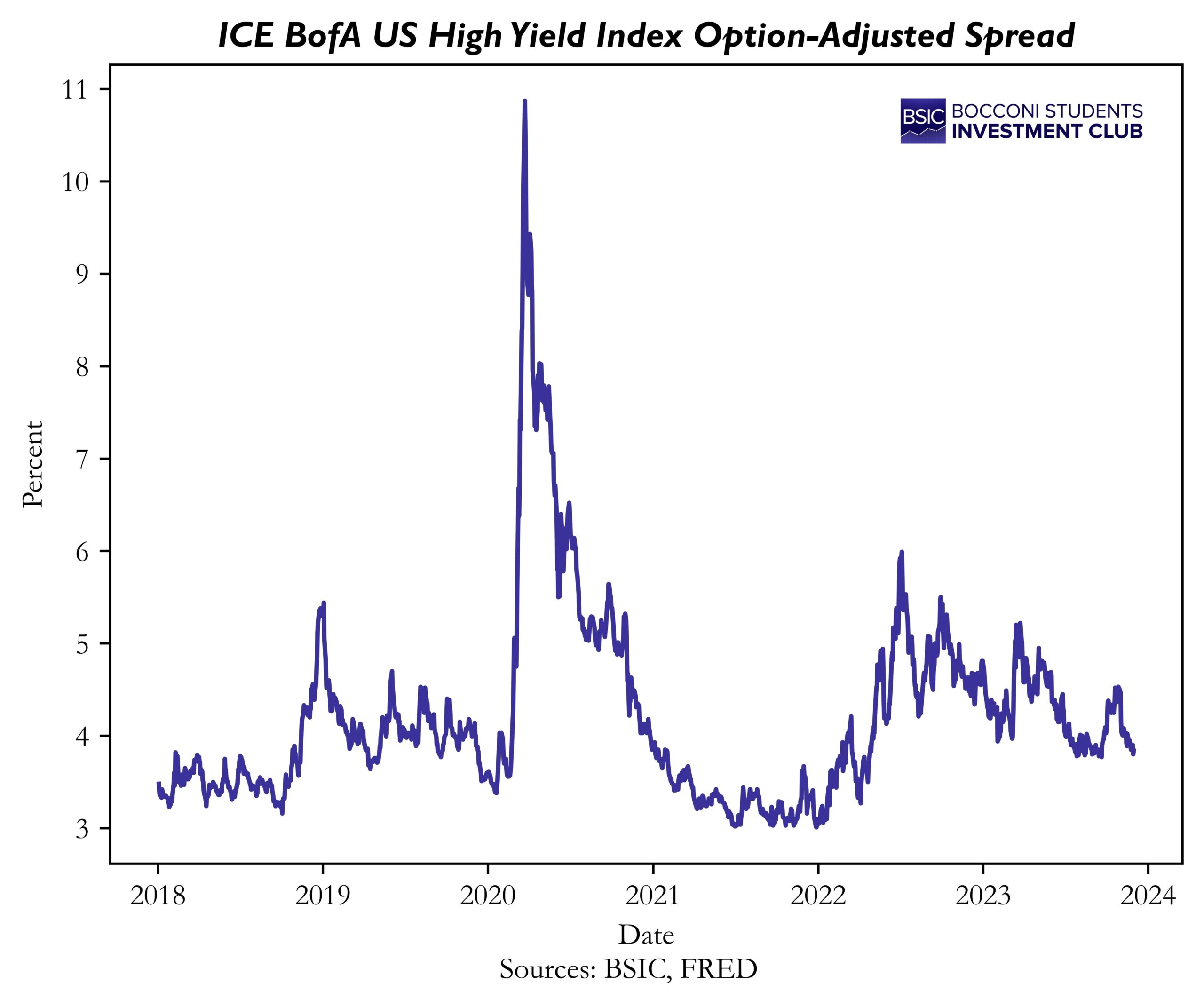

US high yield bonds represent a 1.3 trillion USD market (against 5.3 trillion for investment grade), and now trade on average around 8.30%, down from recent highs. Junk bonds yield can be decomposed into two main components: the risk free rate and the credit spread. Liquidity and term premiums are both encompassed in the credit spread. For US junk bonds, a proxy for risk free rate are similar maturity treasuries, and the credit spread represents the premium required by investors for them to hold the security. Observing the evolution of the aggregate spread overtime gives us an idea of the investor demand for this asset class. Historically, spreads widen in risk-off environments, and inversely during risk-on. Risk-off environment can be defined as a period where investors are more risk-averse, reducing their exposure to low grade securities while favoring lower return instruments (safe havens). This reduced demand impacts the HY market by pushing yields higher, increasing the spread between HY and treasuries (safe haven).

Historical Developments

From the 2008 financial crisis to the 2020 pandemic, financial markets were taking risk (risk-on). Loose monetary policy (Fed Fund rate hovered above 0 for most of the period) eased access to credit for firms, promoting investments and relieving firms from any financing expenses. Combined, risk-on and expansionary monetary policy led to increased demand for higher return assets, driving down yields for junk bonds. The spread between high yield bonds and treasuries shrank from almost 22% to 3% in this period, highlighting both the increased investors’ demand for the asset class and the favorable firm operating environment (reducing firm’s probability of default). It is important to mention the temporary spread widening mid 2015 to 2016 that can be explained by 1) higher market volatility due to Brexit and chinese stock market crash; 2) Falling commodity prices negatively impacting energy-commodity sector (one of the main issue of high yield bonds); 3) expectations of rising Fed funds rate. Lately, as markets started pricing a global pandemic early 2020, spreads initially peaked to more than 10%, before coming down as central banks took action. For comparison, IG spreads peaked at 4% at the height of the pandemic.

In recent years, another driver of credit spreads has been central banks’ corporate asset purchases as part of quantitative easing programs. Launched in 2016 by the ECB (Corporate Sector Purchase Program – CSPP) and followed by the FED (Corporate Credit Facility) in 2020 at the onset of the pandemic, both programs had as objective to stimulate the economy by reducing firms’ borrowing cost. In the states, the FED purchased 13.7 billions of US listed individual bonds and ETFs, with the main criterias being 1) a maturity of 4 years or less 2) investment grade (IG) rating. The purchases were made in both the primary and secondary market. Although this did not directly impact high yield spreads (because the FED purchased IG bonds), there still was a second order effect (mostly through restoring investors faith in the credit market). A peculiar characteristic of certain high yield bonds is that above a certain risk threshold, these bonds will be priced in absolute terms, and not relative to other similar securities. Let’s take an example: a property developer faces solvency issues and has a high risk of defaulting. When pricing this bond, traders will estimate the recoverable value, that is how much is worth the potential collateral in the event of a default. This leads to some bonds trading at 20-30 cents on the dollar, with yields not used anymore as they become irrelevant.

Liability Management: How to Avoid Going Bankrupt

Having analysed the current market situation, we want to now look at what companies themselves can do in order to stay out of bankruptcy courts. When people think about the restructuring groups of investment banks, they often think about the bankers representing different creditor groups in bankruptcy, with each group trying to get as much of the pie as possible in a zero-sum game. However, according to David Ying, the founder of the restructuring group at Evercore [NYSE: EVR], bankruptcy work only makes up around one third of the work that restructuring bankers do. The bulk of their work is actually Liability Management, which entails all the work done to keep the company out of bankruptcy. This is valuable work: after all, bankruptcy often leads to substancial job losses, whilst the process itself is extremely expensive, with all types of advisors (lawyers, bankers, etc.), pocketing millions of dollars in fees. In beauty chain Revlon’s bankruptcy, for example, bankers PJT Partners [NYSE: PJT] pocketed $26.9m, whilst lawyers at Paul Weiss billed nearly $60m, with partners charging more than $2,000 an hour for their efforts.

So, how do restructuring advisors work to keep the companies alive? The key objective for the company is extend its runway, in order to have more time to turn around its business and move away from the bankruptcy danger zone. To that end, there are multiple things that the company can do. The most obvious course of action is raising new money, either from existing or new creditors. However, for many troubled companies this is not possible, given that they will already have used their assets as collateral for prior borrowing. Alternatively, the capital markets may also be unreceptive to low-rated debt, making it hard to borrow money. Therefore, if borrowing new money is not an option, the company will attempt to change the terms on its existing debt via extending maturities, changing payment schedules, or re-negotiating covenants. Finally, the company may also decide to sell off assets or business units, if it determines that it must do so. Note that this point is closely linked to the one made above on covenants, given that high-yield debt often has maintenance covenants that prevent the company from performing significant asset or business unit sales without the consent of the creditors.

Sometimes, simply approaching the creditors in advance can be all you need to do in order to renegotiate liabilities and extend the runway of the company. However, this approach frequently doesn’t work, as creditors may not be incentivized to grant the company more time to pay off its debt. After all, if the debt is properly collateralized, the lender will receive a high recovery on his loan amount, meaning that he may have higher-value uses for his money than letting the struggling company have the money for a longer amount of time. This may be especially true for parties that have bought the debt at below-par prices, as they don’t require 100 cents on the dollar recovery on the debt they purchased in order to make a profit on their trade. Hence, the question for the struggling company becomes how you get your creditors to the negotiation table.

The key to doing so lies in gaining leverage over your lenders, which they have made increasingly easy as they relaxed lending standards in the low interest rate environment that ended in 2022. With base rates at zero, lenders accepted lower coupon payments, along with less covenants and more lenient deal terms. When loans are made, a new entity is frequently created that houses certain assets, against which the company then lends. In the low rate environment, lenders allowed the rules around moving the assets that serve as collateral for the loan to the entity be relaxed, enabling borrowers to move the assets out of the entity that took up the loan into a new, unlevered entity. Therefore, the company starts off with assets and debt in one entity and ends up with two entities, one with debt and one with assets. The appeal of this is obvious: you can now lend against the new entity which houses the unlevered assets, or you can scare your existing lenders into giving you the concessions on the existing debt that you have outstanding with them. We must note, however, that this approach must not be taken too far, given that the extent to which this kind of dealing is possible very much depends on the individual credit agreement. One notorious example of this being taken too far is Apollo Global Management’s [NYSE: APO] work on trying to protect its equity value in Caeser’s Entertainment [NASDAQ: CZR] via moving casinos out of entities that had them as collateral for debt in exchange for guarantees by Apollo, which were worth far less than the Casinos. This dealing and the ensuing controversy was immortalized by Max Frumes and Sujeet Indap ‘Caesars Palace Coup: How a Billionaire Brawl Over the Famous Casino Exposed the Power and Greed of Wall Street’.

Restructuring: How to Deal With Doing Bankrupt

Financial restructuring usually arises when a debtor has outstanding obligations that represent difficulties for them to service, usually because of misalignments between the company’s capital structure and the current economic and business environment. For companies in distress, the amount of debt repayments, and other cash outflows related to pre-established contractual obligations such as pensions or leases, are very high relative to the operating cash flow of the firm, prompting difficulties. Moreover, even though it is not simple to anticipate, and there is no absolute formula, a company can show sign of distress that might signal a possible restructuring. Fully drawing a revolving credit facility, deteriorating credit metrics, delayed payments to suppliers and sale leasebacks are all possible signals of distress within the company, hence the need for changes within the company.

The main causes of financial distress are macro and external events, shifts and trends that disrupt industries, and company-specific factors. For example, the 2008 Financial Crisis, which caused severe harm to the global economy, resulted in companies as General Motors [NYSE: GE] or Chrysler [NYSE: STLA] to file for bankruptcy. Both companies were eventually bailed out and received assistance from the US government. Moreover, regulatory changes, changes in consumer preferences, and technological innovation can also drive companies to restructure themselves. For example, even though they didn’t declare bankruptcy, but nearly did, Juul, the e-cigarette company, has had to significantly reduce their operating expenses as judicial decisions have prevented their products from being in the market. Lastly, company specific factors such as operational inefficiencies, overreliance on debt, an overly competitive landscape, or corporate fraud, can also lead to bankruptcy. For example, Enron, the America-based energy company, filed for bankruptcy following an accounting scandal.

There are two main types of restructuring mechanisms: out-of-court and in-court restructuring. The assumption behind either form of restructuring is that a turnaround is achievable, as long as the right strategic decisions are made and the capital structure is normalized to suitable for the company profile, and a Chapter 7 liquidation is unnecessary. Out-of-Court Restructuring is when the company in distress attempts to resolve its financial distress and insolvency issues without the intervention of a court, and instead directly negotiates with the creditors. This is a faster and less expensive process, but it requires the company to have sufficient liquidity and a less complex capital structure, meaning fewer creditors and tranches of debt. It has plenty of advantages, which include less business disruption, as well as more cost-efficiency, and more liberty is given to the debtor to make the necessary changes to drive growth and improve margins. Some out-of-court restructuring techniques include revision of interest rates, repayment schedules, extension of maturity dates, defer interest payments, debt-for-equity swaps, debt-for-debt swaps, increase in payments-in-kind (PIK), new debt issuance, new equity injection, distressed M&A, debt repurchases, among others. However, the debtor is still vulnerable as creditors can continue their collection efforts in case of breaches, as well as suppliers may avoid working with a company because of the increased risk. Usually, most cases begin with attempts to negotiate a consensual out of court restructuring, but not all are successful.

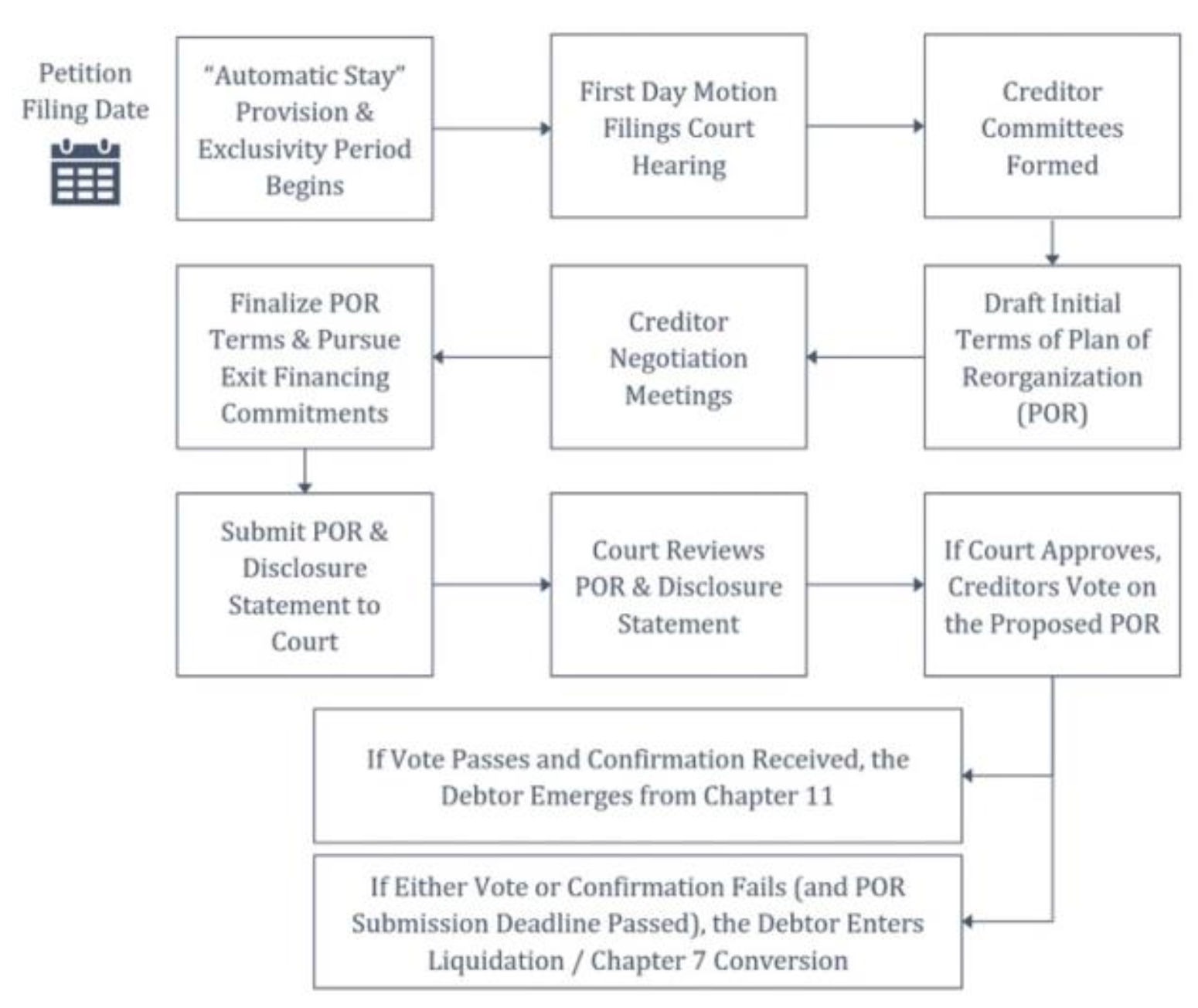

On the other hand, In-Court Restructuring occurs when there are too many creditors to achieve consensus, or because of the existence of issues with leases and pension obligations, forcing the company to renegotiate its liabilities in court, leading to Chapter 11. This mechanism intends to serve as rehabilitation and allow a fresh start for the troubled company, while preserving the value attributable to the debtor. It is often criticized for being expensive, time-consuming, disruptive, but the Court provides plenty of tools and resources that are likely to have a positive impact for the debtor and contribute towards its turnaround. Some of the advantages that an In-Court process brings are that the automatic stay provision goes into effect immediately, meaning that creditors are restrained from continuing their collection efforts while relieving the debtor from a large burden, and allowing them to solely focus on the reorganization plan. Also, it allows for Debtor in Possession Financing (DIP), for cancellation of burdensome contracts, among others. However, it also has downsides as expensive restructuring advisory and court fees, can be time-consuming if either side has objections, as well as the list of claims from creditors, as well as the assets and liabilities of the debtor are disclosed publicly, which can be inconvenient for some both debtors and creditors.

Moreover, there are three main types of approaches to filing for Chapter 11: the Traditional, the Pre-Negotiated and the Pre-Pack. The Traditional approach is when no negotiation was done in advance of the filing for bankruptcy, so they have to start from zero, making the process more time-consuming. The Pre-Negotiated approach is when the debtor has held prior negotiations with creditors to discuss the reorganization, but there is no full support nor there has been any approval yet as there has been no petition in court. Lastly, the Pre-Pack approach that is when before the actual petition date, the debtor and the creditors have negotiated a plan and held a preliminary vote to confirm a majority support. It is even possible for the debtor to emerge from bankruptcy even before setting a foot in court.

Source: BSIC

Finally, one of the most important components of Chapter 11 is the priority of claims. The hierarchy of the distribution is established by the Absolute Priority Rule (APR), which requires senior claims to be paid in full before any subordinate claim receives anything. The order is as follows:

- Superior & Administrative Claims: Legal and professional fees, DIP, post-petition claims

- Secured Claims: Claims secured by collateral

- Priority Unsecured Claims: Employee claims and government tax claims

- General Unsecured Claims: Usually represent the largest claim holder group and include suppliers, vendors, unsecured debt

- Equity: Usually receive nothing

Recent Trends in the Restructuring Space

In a period of rapidly rising interest rates, amongst other exogenous shocks, more and more over-leveraged firms struggling to refinance their debt have found themselves at best, conducting liability management transactions, and at worst, in bankruptcy court. With recent rulings swinging in the favour of the debtors, we have seen increasing levels of ingenuity from companies and their restructuring bankers to move assets in and out of credit boxes in order to raise new capital. Although this has created market dislocations for certain creditors, the zero-sum nature of bankruptcy has led to new forms of creditor-on-creditor violence. This section will examine two recent case studies: the first being Yellow Corporation’s bankruptcy (formerly YRC Worldwide), a near-century-old trucking company, and the second being Angelo Gordon’s involvement in the Revlon and Serta Simmons Bedding bankruptcies.

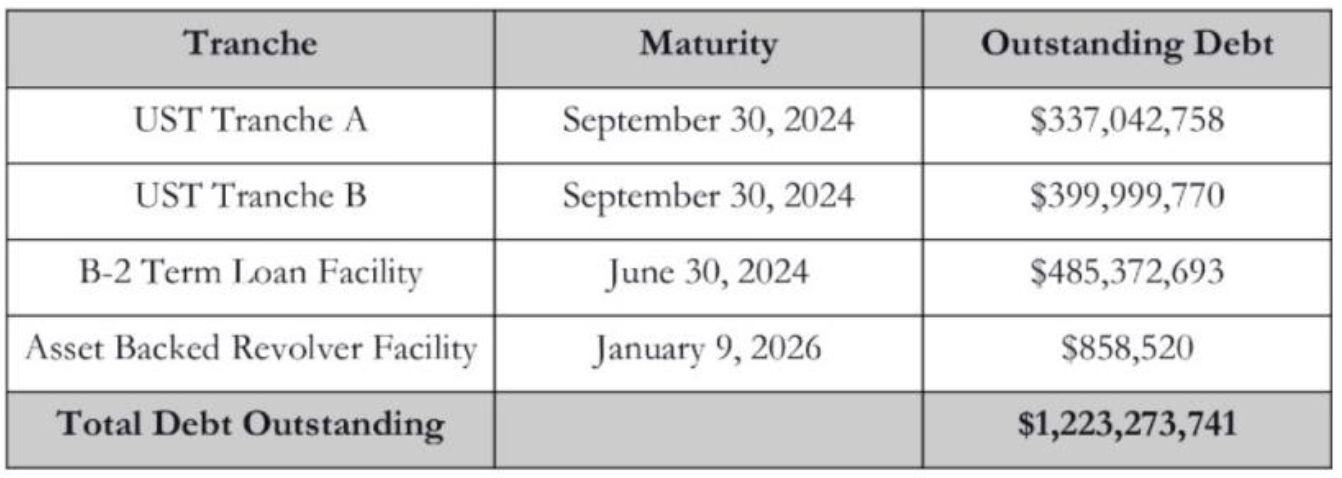

Yellow filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on August 6th 2023, only three years after receiving $700m, pandemic-inspired bailout from the Trump administration. Although these direct loans were intended for companies that were “business critical” to the American economy, the loan to Yellow was heavily scrutinised at the time by the Congressional Oversight Commission due to the company’s troubled financial position (Yellow had a net loss of $104m the year prior and $880m in outstanding debt covered by an EBIT of only $16m) and the company’s affiliation with the Trump administration, considering its financial backing by Apollo Global Management [NYSE: APO], whose co-founders Leon Black and Josh Harris had close ties with the former President. This loan was later investigated by The Office of Audits in May 2023 , which identified control weaknesses in the approval process and a rather vague definition of “business critical to maintaining national security”. Ultimately, it was ongoing troubles with labour union strikes that caused customers to flee and sealed Yellow’s fate. Prior to filing for bankruptcy, the firm shut down all operations and laid off all 30,000 employees with $1.2bn of debt outstanding as seen in their capital structure below.

Yellow’s Chapter 11 filing intended to begin the sale of essentially all of the debtor’s assets, which is known as a section 363 sale under the bankruptcy code. Given that the company is selling all of its assets, it raises the question of why this is not a Chapter 7 liquidation like most people would expect. The answer lies in the control that the firm will have in Chapter 11 over the disposal of assets, unlike in Chapter 7 where a trustee would be in charge of the liquidation. A section 363 sale is a unique benefit of bankruptcy protection where firms can sell off assets, free and clear of all liens, to repay creditors. This is different to outside of bankruptcy where buyers can only purchase assets with the correlated liabilities. Consequently, section 363 sales make a debtor’s assets much more marketable to prospective buyers in an auction. One of the critical features of section 363 sales is the stalking horse bidder. This is typically the first bidder, chosen by the debtor or their advisers, who submit a floor price for the auction which following bidders must exceed. The stalking horse is often chosen because they have done some due diligence on the assets and are willing to make a reasonable offer, ensuring that assets are not sold at unreasonably low prices. Evidently, being a stalking horse bidder seems risky; you have to expend many resources in conducting this due diligence in an expedited process, whilst the asset’s distressed nature may conceal its intrinsic value. Since stalking horse bidders are essential, bankruptcy courts have provided many incentives to these bidders, including expense reimbursements, exclusivity agreements and breakup fees.

Yellow’s predicament underscores the tumultuous nature of bankruptcy’s asset sale process—a performance that’s not short on twists and turns. Given the liquidation treatment of Yellow’s case, a clash emerges over divvying up the spoils according to the absolute priority rule and juggling with Debtor-in-Possession (DIP) financing. DIP financing is a special form of financing provided for companies in bankruptcy that typically violates any absolute priority rule and is put right at the top of the capital structure. With Yellow hitting the operational brakes, a creditor’s chance at a financial comeback is as good as their spot in the capital structure. Ducera, Yellow’s advising bank in this saga, swiftly caught wind that Uncle Sam and the revolver facility would not be interested in providing post-petition financing since it wouldn’t spice up their returns. Consequently, they looked at the B-2 Term Loan Facility, which Apollo held among other creditors. Apollo’s proposal of DIP financing was a total of $643m, with $142.5m being new money (i.e., fresh capital) and the rest being rolled up, meaning $500.5mm of Apollo’s pre-petition debt is now a part of the super-priority DIP tranche in the capital structure, putting them first in line for repayment, above the US government and all other creditors. The $142.5m loan would have had an annual interest rate of 17% and a potential closing fee of up to $32m. This is where Yellow’s bankruptcy story starts to get a bit messy. A Boston-based investment fund called MFN Partners, bought up more than 22m shares in Yellow’s equity, accounting for a 42% stake. They then offered their own DIP financing, with friendlier terms such as an extended maturity and reduced fees, and crucially a roll-up for their equity. Apollo immediately contended this in court, arguing that an equity holder who sits lower in the capital structure should not be able to prime the rights of creditors higher in the capital structure to provide DIP financing. To complicate matters further, Yellow received a third DIP proposal from Estes Express Lines, a competing freight operator. Estes offered to provide $230m in new money with lower interest and fees than Apollo, making the DIP financing decision even more confusing. Due to all this contention, Apollo left the case and sold their $500m loan at par to the Citadel Credit Fund, who immediately provided their own DIP proposal, which was the one that Yellow ultimately accepted. Citadel can now use its DIP financing to perform credit bids, where they bid their secured debt against the purchase price in a sale to acquire Yellow’s assets, hence protecting the value of their collateral.

Although Yellow’s case is ongoing and has yet to reach an ending, it has shone a light on the aggressive nature of creditor on creditor violence, even if that creditor is the United States Government. The next case study we will assess is the contradictory roles that Angelo Gordon played during the Revlon bankruptcy and the Serta Simmons Bedding bankruptcy. Angelo Gordon is an alternative asset manager with assets under management of $73bn that specialises in distressed debt and other credit products and was acquired by TPG [NASDAQ: TPG] for $2.7bn in November. The head of the firm’s distressed debt and corporate special situations team is an industry veteran, who previously worked at Blackstone’s [NYSE: BX] GSO Capital Partners, where he architected the “manufactured default” we discussed in this article. The cosmetics company, Revlon, filed for bankruptcy on June 16th 2022 following a series of supply chain disruptions and inflationary pressures, facing a heavy debt load of $3.6bn. Angelo Gordon strategically banded together with a majority group of other creditors in the same tranche to provide rescue financing in May 2020. Consequently, other creditors were left out of this deal and recovered a fraction of the face value of their claims. Angelo Gordon, alongside with Glendon Capital Management, King Street Capital Management and Oak Hill Advisors, received ownership of the company in exchange for the debt reduction agreement, wiping out the equity value of existing shareholders.

In the Serta Simmons Bedding bankruptcy however, Angelo Gordon was on the receiving end of the stick. Like in the Revlon bankruptcy, a majority of lenders banded together to provide a controversial $875m loan refinancing in an up-tier exchange executed in 2022. This allowed them to lend fresh capital and simultaneously convert their prepetition debt into more senior loans, putting them higher in the capital structure than the minority lenders that did not participate in the exchange. The only difference this time was that Angelo Gordon was not included in this exchange. Angelo Gordon, alongside Apollo and LCM Asset Management, insisted in court that all lenders should have been given the opportunity to participate in the transaction, not just a select majority, in order to qualify as an “open market operation”. Serta responded to the court that they had evaluated multiple offers and had rejected a less favourable proposal from Angelo Gordon and Apollo. Federal bankruptcy judge David Jones in Houston dismissed the arguments made by Angelo and Apollo, marking a landmark ruling on creditor-on-creditor violence, in an industry which has typically yielded few verdicts. The ruling has set precedent for more future deals pitting lenders against one another and may send the leverage loans market into a frenzy, according to some analysts. The guarantee from the seniority of leveraged loans attracted many long-only asset managers and vehicles that bundle hundreds of these loans together to create collateralised loan obligations (CLOs). The landscape of leveraged buyouts has witnessed a substantial shift over the past decade, with the loan market playing an increasingly prominent role in the financing mix. This evolution has resulted in a diminished presence of junior capital to absorb losses during bankruptcy or restructuring. According to Moody’s, first-lien loan holders historically recovered approximately 95 cents on the dollar in restructurings from 1987 to 2019. However, this figure plummeted to 73 cents in 2021 and 2022. The rating agency sounds a cautionary note, asserting that in this “new world of LBOs… even first-lien lenders are poised to face significant impairments.” Coupled with the recent increase of covenant-lite loans, we can expect to see more ingenuity from companies to reorganise their balance sheets, and also riskier and more aggressive tactics from these savvy vulture investors in the debt restructuring fights to come.

Defaults rates/HY market today

Today’s high rate implies challenging pressures both on the demand and supply side. With tighter credit conditions, consumers are less inclined to spend, reducing aggregate demand. On the firm side, this leads to significantly higher financing costs, burdening highly leveraged firms. In this tight credit environment and increasingly tense geopolitical context, firms who’ve previously generated low cash flows and face operational difficulties have seen their default probability skyrocket. Markets reacted to this by requiring a higher spread to hold such assets (3.84% today against 3.00% early 2022). Firms with higher credit ratings, reflecting an underlying lower solvency risk, have much tighter spreads (1.11% for IG).

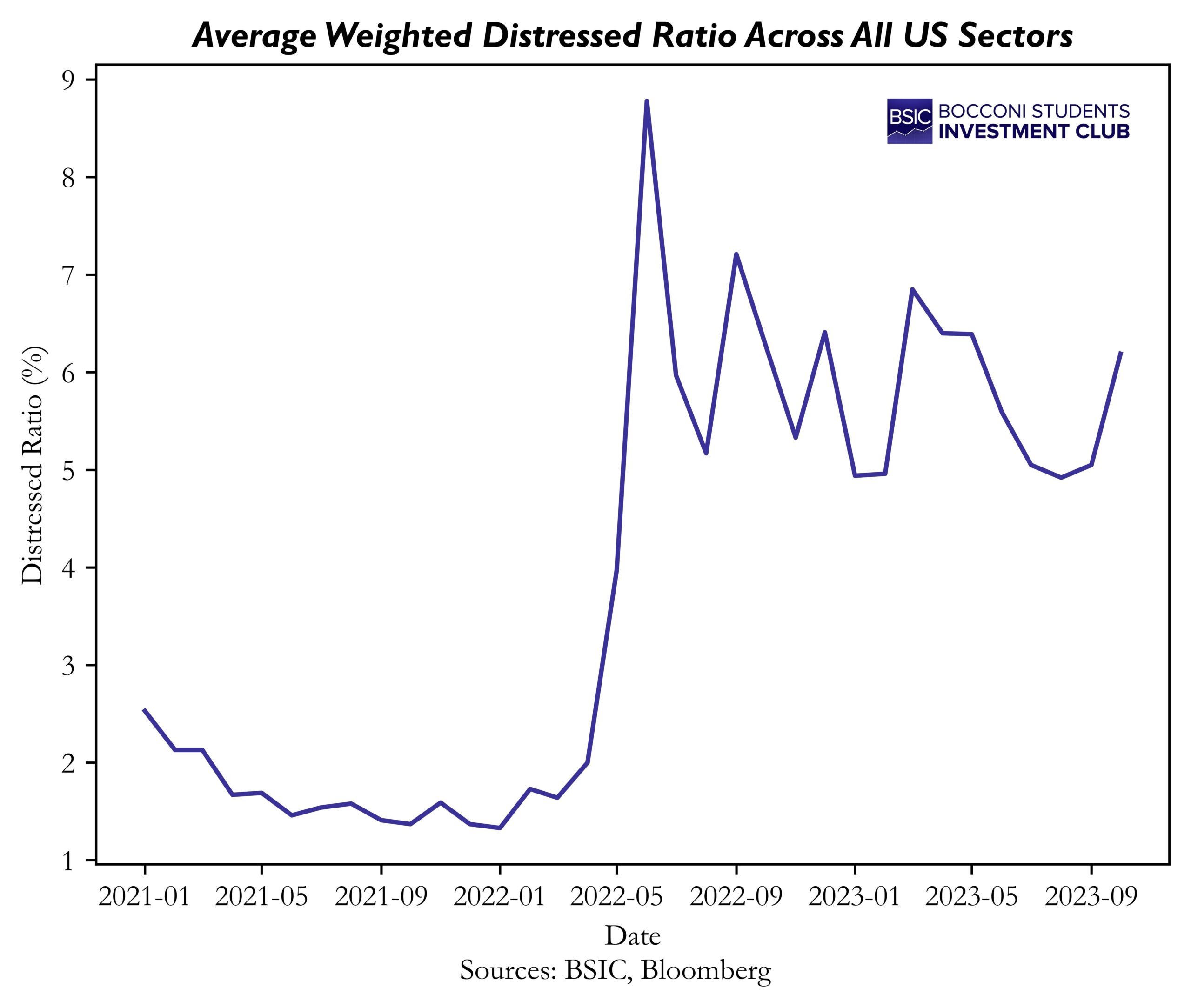

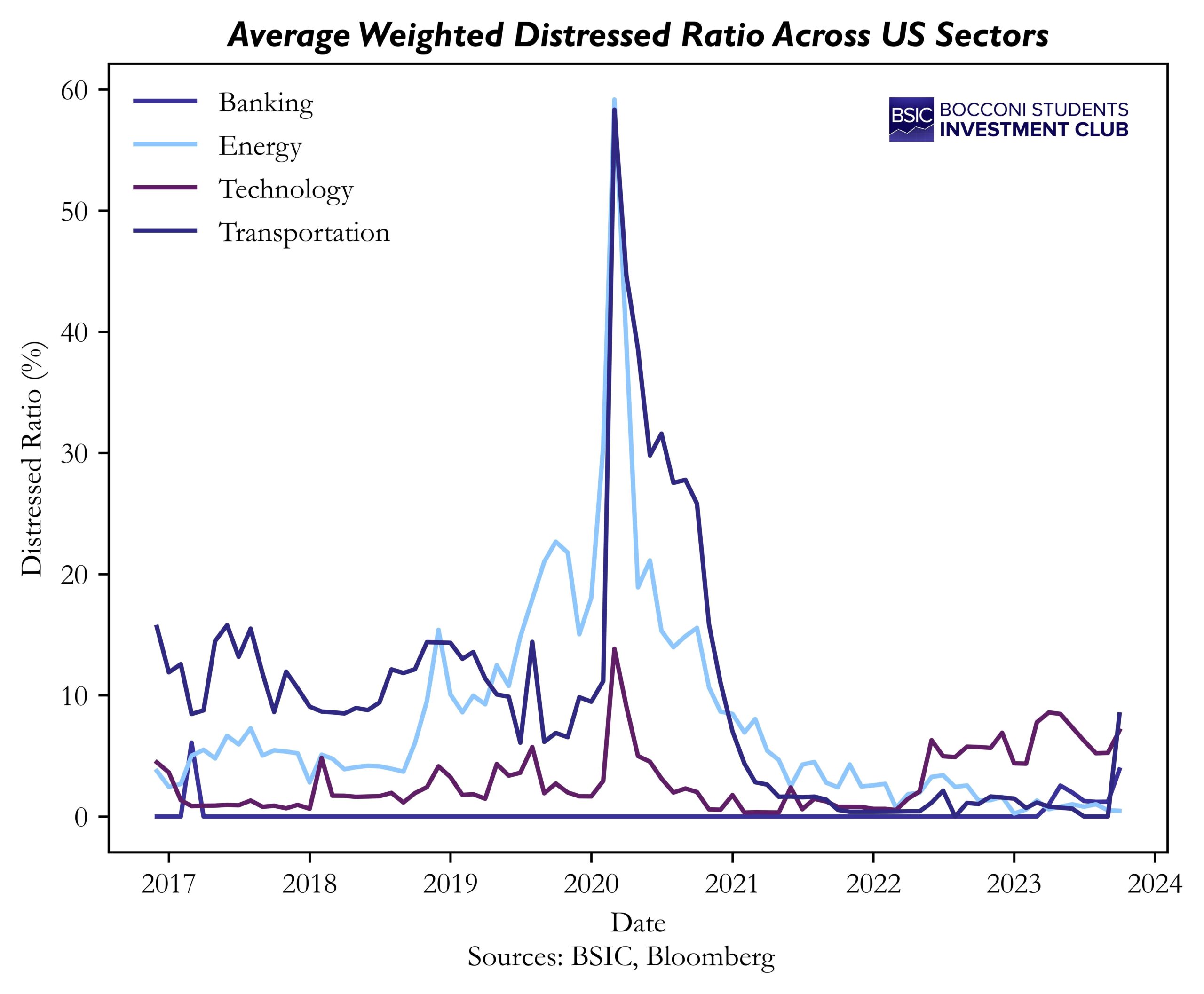

The transmission of higher borrowing costs into the real economy can be seen through the recent sharp rise of US corporate defaults. The US trailing 12 months speculative grade default rate computed by S&P shows a peak of 7% at the climax of the covid pandemic, followed by a drop of less than 2% in early 2022. From this moment onwards, the default rate has been steadily rising, reaching 3.24% in June 2023. Distressed debt figures paint a similar picture. In mid 2022 there was a huge spike in the US Distressed Credit Market Value to Total US Credit Market Value ratio, normalizing at the beginning of 2023, but picking up pace again as we approach the end of the year. Taking a closer look at 4 of the biggest sectors, we see that the Banking sector has been extremely resilient, despite the sudden spike towards the end of 2023.

Trade Pitch

As previously pointed out, during the last couple of months we have seen further tightening of the HY to US Treasury spread. There are two main drivers behind this move, one being the overall market consensus that the Central Banks have reached the peak of their rate-hiking cycles, and the other being low liquidity levels. Overall volume has been squished since October as market participants stray from unnecessary risk on their books as the end of the year approaches. Judging by past performance and financial theory, moving into a new period of lower interest rates, as central banks start cutting rates, it would be expected for said tightening to continue.

However, we see a potential widening in Q1, as a recession and a possible default cycle loom over major economies, especially in Europe, mainly driven by systemic risk from mortgages. The sticker-than-expected inflation, driven by a still resilient consumer, would serve as an obstacle for central banks to deliver cuts before the end of H1. We hold the view that cumulative effects of monetary and fiscal tightening would sooner or later weigh down on the economy, further widening the HY spread, and increasing credit default rates throughout the US and Europe.

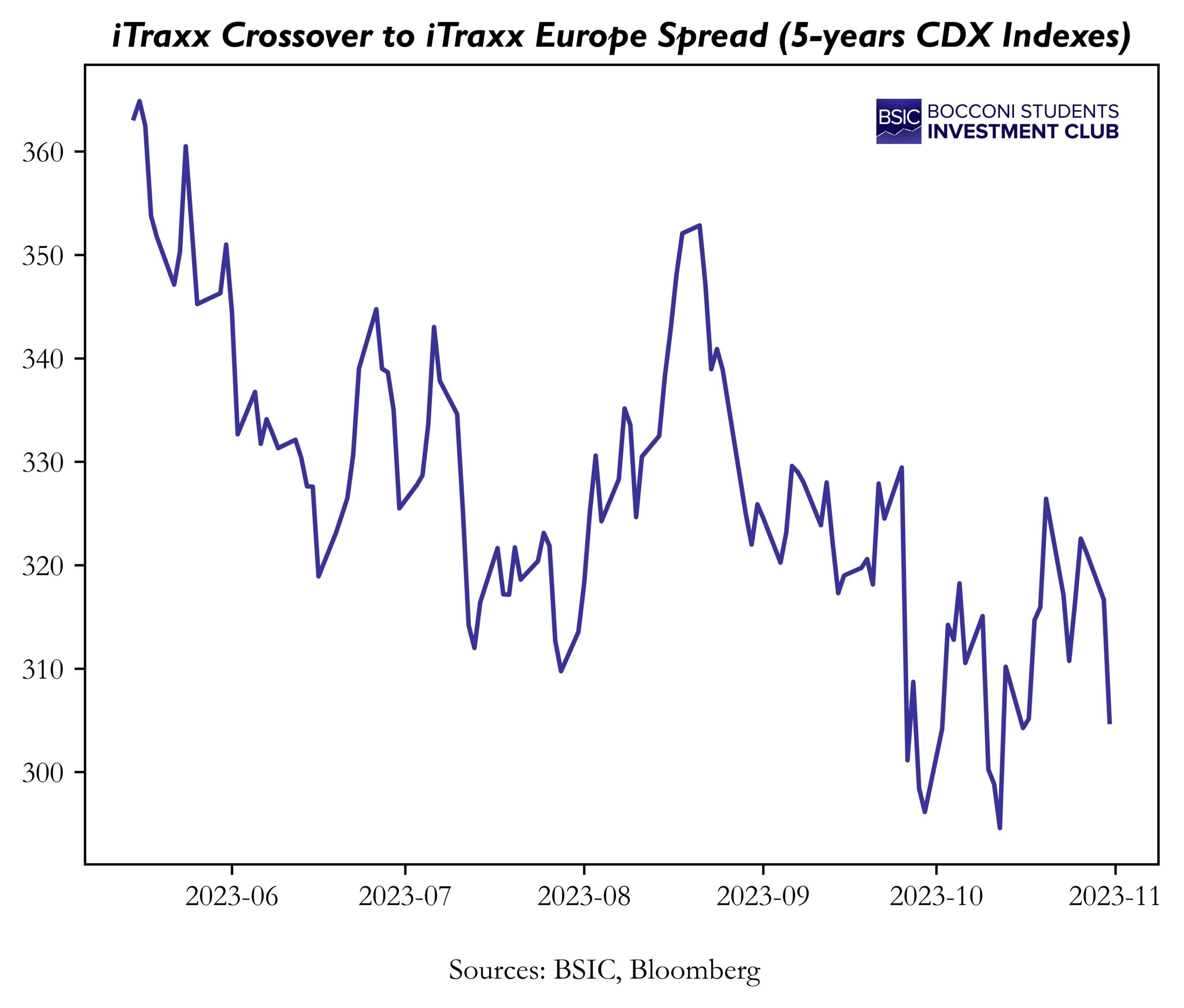

Because of that we propose a decompression trade. Spread decompression occurs when spreads of lower-quality credit widen in comparison to those of higher-quality credit. Given the inverse relationship between price and yield, a shift towards safer, higher-quality bonds leads to lower yields and higher prices. Our securities of choice are the two iTraxx indices: iTraxx Europe and iTraxx Crossover. The iTraxx Europe index is a credit default swap (CDS) index that incorporates 3, 5, 7, and 10-year maturities, with a new series determined semi-annually based on liquidity. It comprises 125 equally-weighted European names and provides insight into credit risk for investment-grade European companies. Additionally, the iTraxx Crossover index focuses on sub-investment-grade entities, specifically the 75 most liquid ones, offering a view into credit risk for riskier European companies. Total Return indices are calculated and published hourly for iTraxx Europe and Crossover, measuring the performance of the respective on-the-run iTraxx CDS contracts.

Our setup is a pretty standard one, selling protection on Itraxx Europe and buying protection on Itraxx Crossover, or in other words, going short and long respectively, betting on a widening of the spread of IG and HY European corporate credit. The two legs ensure an almost entirely market and carry neutral trade. Due to the nature of the trade itself, our stop-loss and take-profit conditions won’t be centered around “technical thresholds”, but would be rather more “situationally oriented”. The catalysts we are looking for are various, anything from a huge wave of deleveraging to mass refinancing of debt would be a clear indicator of an impending systemic crisis. Since the main risk to our trade is a premature start of a rate-cutting cycle in Europe, or in the US, we would cut losses if such a scenario unfolds.

0 Comments