Introduction

Michael Saul Dell, an American billionaire investor, is the founder and CEO of Dell Technologies Inc. [NYSE: DELL]. According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, he is the 13th richest person in the world, as of October 3, 2024. Born in Houston in 1965 to a Jewish family, Dell quickly gained an interest in computers during his childhood – he got his first computer, an Apple II, at age 15 which he disassembled to discover how it worked. Despite this clear interest in technology, Dell took up pre-med at the University of Texas in 1983 to satisfy his parents’ desire for him to become a doctor.

While he was still a freshman at the University of Texas, Dell began selling upgrade kits for personal computers. This business grew, and, in January 1984 at the age of 19, Michael Dell registered his company as PC’s Limited. His strategy was simple: to sell directly to customers by manufacturing personal computer (PC) systems only after they were ordered. Dell’s revolutionary direct-to-consumer sales strategy would allow PC’s Limited to provide the most effective computing solutions to customers’ needs, as well as benefit from massive cost savings.

In 1985, the company launched its first own-design computer, the Turbo PC, containing an Intel processor capable of running at a maximum speed of 8 MHz. 1987 saw the decision to drop the ‘PC’s Limited’ name in favour of ‘Dell Computer Corporation’ to better reflect the company’s position in the industry. Under this new name, Dell began a global expansion with the opening of its first international operations in Britain; in the next four years, 11 more global operations followed. Finally, in 1988, Dell Computer Corporation underwent an IPO where it offered 3.5m shares at a price of $8.50 each. As a result, the company raised $30m and its market capitalisation grew to a staggering $85m.

The 1990s saw massive growth for the company, thanks in part to the Dot-com bubble at the tail end of the decade. In 1992, Dell Computer became a top five PC maker worldwide and Michael Dell was crowned the youngest CEO of a Fortune 500 company at the time. The launch of its e-commerce website in 1996 positioned Dell Computer as one of the first companies to sell computers directly online. This allowed the company to gain greater exposure to the consumer market, which massively boosted sales. Up until the turn of the century, Dell Computer gained market share whilst rivals such as Compaq, Gateway, IBM, and Hewlett-Packard (HP) struggled. In 1999, Dell Computer surpassed Compaq to become the largest PC manufacturer in the United States.

The Dot-com crash in 2000-2001 saw Dell Computer and its rivals experience declines in revenue. However, Dell fared better than its competitors due to its low operating costs: in 2002, operating costs made up only 10 per cent of its $35bn revenue whereas HP and Gateway saw costs of 21% of revenue and 25% of revenue respectively. Along with the Dot-com crash, other key events in the early 2000s would come to impact Dell and its business model. Firstly, the 2002 merger between Compaq and HP which consolidated the product lines of the second- and fourth-place PC maker posed a direct threat to Dell’s competitive position and market share. In fact, the newly combined entity briefly took the top spot in PC manufacturing before Dell regained its lead. Secondly, Dell emphasised a horizontal organisation that relied heavily on the PC market. This market had matured and was facing slower growth, with the industry shifting towards delivering an end-to-end IT product to customers.

As a result, the company began to expand its product lineup to include higher-margin products such as servers, storage devices and printers. The change of name from Dell Computer Corporation to Dell Inc. embodied this diversification. The company would also experience a change in leadership: Michael Dell stepped down as CEO in March 2004 and Kevin Rollins took his place. However, despite the diversification, the company remained heavily reliant on the US PC market, with a large chunk of revenue deriving from sales of desktop PCs to commercial and corporate customers.

Moreover, Dell’s reputation as a seller of established technologies at low prices would hurt the company as analysts turned towards ‘innovative’ companies as the next source of growth in tech. Dell’s low spending on R&D compared to rivals like HP and Apple would prevent the company from making inroads into thriving sectors, such as MP3 players and mobile devices.

In 2005, Dell was under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for improper accounting, in particular its failure to disclose payments from Intel. Along with a misrepresentation of profits, these practices allowed the company to overstate earnings to meet targets and mask declining performance. Whilst Dell did not admit nor deny the allegations, they would later agree to settle with the SEC and pay $100m in fines. Michael Dell would pay a $4m fine himself.

Despite the acquisition of Alienware, a leader in the high-end gaming PC segment, in March 2006 and an overhaul of its poor customer service, with expenditure of $100m on online tools to reduce call transfer times, these events marked significant challenges for the company. 2006 would mark the first year where Dell saw slower growth than the PC industry average. It would also lose its title of largest PC manufacturer to HP in Q4 of the same year.

With declining growth and below-expectations earnings reports in four out of five quarters, Rollins resigned as CEO in January 2007 and Michael Dell assumed the role once again. In his second stint as CEO, Dell would engage in several cost-cutting and diversification strategies in an attempt to improve the company’s financial performance. Dell announced the termination of around 9000 jobs between 2007 and 2008, as well as the shutting down of various plants producing desktop PCs for North America. The company engaged in a failed attempt to penetrate the growing tablet market, with its competition to the iPad, the Dell Streak, failing commercially due to an outdated operating system and numerous bugs. Also, Michael Dell would begin a $13bn acquisition spree of more than 20 firms to diversify its portfolio towards online storage and IT services. The largest deal was its $3.9bn acquisition of Perot Systems in 2009, with the hopes of greater competition with IBM and HP.

Despite this transition towards an enterprise solutions provider, Dell was unable to convince the market that it could thrive in a post-PC world. The PC market still accounted for nearly half of the firm’s revenues and its loss in market share to Lenovo in 2011 did not make Dell’s outlook any brighter.

The Salamander comes slithering in – the lead up to the acquisition & the take private

The dire performance of the 2000s culminated in a -43% performance of Dell stock in the period following Michael Dell’s come back as CEO. The abysmal performance in the year leading up to the acquisition saw Net Income drop by 72%. On the back of this struggling period, Michael Dell approached the board in August of 2012, forming a Special Committee to explore a possible privatisation of the business. The committee was led by Alex Mandl and utilized J.P. Morgan [NYSE: JPM] & Debevoise & Plimpton LLP as independent financial and legal advisors.

It all comes down to February of 2013 when the original deal was put on the table, marking the largest proposed LBO since the 2008 financial crisis. The initial deal put on the table included a $13.65 cash bid for the outstanding Dell common stock not held by Michael as he rolled over his 16% stake & contributed some of his personal capital, representing a 25% premium to the closing share price on January 11, 2013 (last unaffected trading day) and an Enterprise Value of c. $24.4bn. The deal was also funded in part by Microsoft [NASDAQ: MSFT] which provided Software for Dell computers, investing $2bn in the deal.

After the initial deal was put on the table, the Special Committee advised by Evercore [NYSE: EVR] initiated a go shop period in which various parties were brought to table for a 45 day-window to solicit, evaluate and negotiate alternative proposals. By March, several interlopers arose with Blackstone [NYSE: BX] and infamous corporate raider Carl Icahn leading the charge. Other sponsors including KKR [NYSE: KKR] and TPG [NASDAQ: TPG] chose not to submit bids in the process. In April, the team at Blackstone had pulled the deal leaving only Icahn Enterprises and his inflammatory comments including “All would be swell at Dell if Michael and the board bid farewell.” He agreed that the shareholders were being treated unfairly and that Dell & Silverlake were not paying a fair price ultimately stating that “they were getting hosed.” However, removing the public shareholders from the equation and eliminating various dividends and stock buybacks the sponsors believed that there should be enough cash flow left over to cover interest payments. Silverlake’s exceptional track record at the time included a 213% return on Skype, 730% on Seagate Technology [NASDAQ: STX] and 430% on Avago Technologies. Despite fears of the LBO being capped at 11% annualized returns, Dell was certain that he could outperform that following the forma mentis everything is bigger in Texas. Icahn did not give up and by June he had pushed for a leverage recapitalization (operation in which a company revises its capital structure, replacing the majority of its equity with both senior and junior debt), hoping for dell to pay a premium to investors and issue warrants that would allow them to buy shares if the turnaround was successful. On his side and pleading the case for the 2nd largest shareholder, Southeastern Asset Management, was a famous tech executive (whom Forbes believes to be former Compaq CEO Michael Capella). The unsuccessful nature of the appeal led to a hail mary by Icahn – purchasing ~$1bn in shares from Southeastern. Ultimately, all of Carl Icahn’s efforts were in vain as in October of 2013 in the heart of Silicon Valley, Michael was finally able to say to those present at the announcement:

“It’s great to be here and to not have to introduce Carl Icahn to you.”

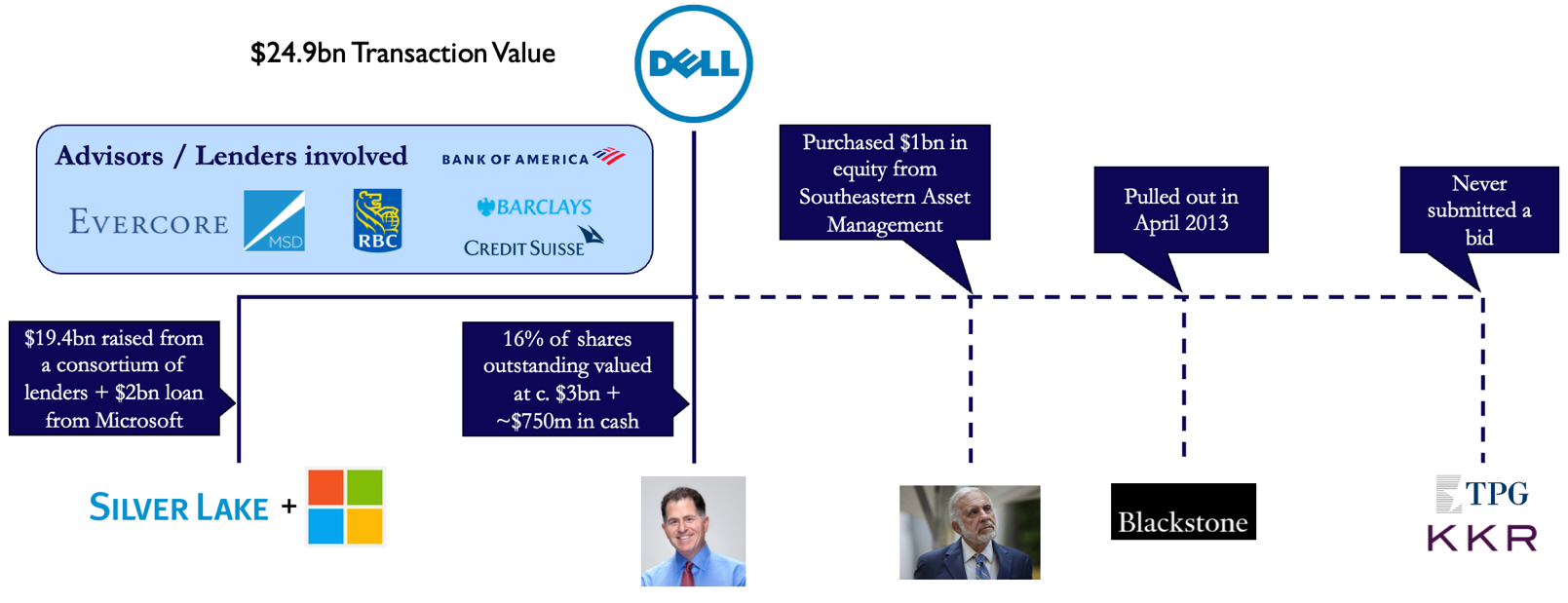

The deal was concluded on October 29, 2013 at a final Enterprise value of $24.9bn, the final deal structure was the following:

Source: BSIC

Post take private

The new Dell posted promising metrics after the take-private: moving away from the direct selling business model that had made Dell, in 2013 they had more than 140,000 channel partners corresponding to roughly $16bn of revenue, up from zero in 2008. Dell had finally gotten their sales force to cross-sell and this is where Dell saw some real growth, something it couldn’t seem to do when it was a public.

In the 11th hour, before we saw one of the most iconic private equity backed corporate takeovers in the last century, Silver Lake was seen attempting divest Dell’s core PC business in a possible sell-off. Silver Lake had approached Hewlett-Packard, Lenovo and Huawei to shop around for potential interest in the PC business.

Dell’s PC business was once one of the defining forces in the personal computing business, but now none of their main competitors even showed interest. HP was not interested because it was in the process of splitting into two companies, one devoted to PCs and printer sales, the other to corporate computing hardware and services. Lenovo concluded that an acquisition of Dell’s PC business wouldn’t go over well with regulators in the U.S. Huawei wasn’t in the PC business and made public the fact that it had no intentions to enter it. This was even considering the fact Silver Lake was seeking a fraction of the PCs business annual revenue, Dell had been running this part of the business on a loss and making money only though cross selling. It wasn’t clear if Dell was even consulted in the shopping of the business.

EMC Merger

Then incredibly shortly after, by the next Monday, Dell proposed to pay a combined $67bn to acquire the data storage company Egan, Marino, and Curly (EMC) [NYSE: EMC] and its subsidiary VMware [NSYE: VMW] in what is the largest proposed technology M&A deal in history. The deal would be one of the most important M&A transactions of all time, Dell would be acquiring a company almost double its size, and as we look back, this is one of the most well carried out cases of financial corporate engineering in history.

The merger with EMC created a unique family of businesses that provided essential infrastructure for organizations to build their digital future, transform IT and protect their most important assets. Dell has had the flexibility and agility to focus completely on customers and invest for long-term results, as a private company and the transaction united Dell’s strength with small business and mid-market customers with EMC’s strength with large enterprises to fuel profitable growth and generate significant cash flows. The acquisition also gave Dell ownership of what would soon be their crown jewel, VMware, a pioneer in virtualization of corporate technology infrastructure.

The deal was struck on October 12, 2015, and since Silver Lake and Dell were buying out a competitor about twice their size, they had to get very clever with how they acquired it. The deal was struck with a cash and stock mix. EMC stockholders received approximately $33.15 per share in a combination of cash as well as newly created tracking stock linked to a portion of EMC’s economic interest in the VMware business.

The cash part of the deal was primarily financed through debt: Dell took on significant debt, approximately $50bn, to fund the cash portion of the deal. This was a leveraged buyout, meaning Dell used the target assets and cash flows to help finance the acquisition. And the stock part of the deal is where things got interesting; EMC shareholders received approximately 0.111 shares of new tracking stock for each EMC share.

This was a brilliant piece of financial engineering, as an alternate way to pay in stock and lower their debt burden to finance the cash part of the acquisition, Silver Lake and Dell listed a publicly-traded tracking stock that represented a 53% ownership in VMWare.

At the time of acquisition, VMware was a publicly traded company but 81% owned by EMC, Instead of fully acquiring VMware and integrating it into Dell, Dell created a publicly traded tracker stock tied to VMware’s performance. The VMware tracker stock was created and listed separately from common VMware stock [NYSE: VMW] but instead [NYSE: DVMT]. The tracking stock was issued to EMC shareholders as part of their stock portion of the deal, the stock allowed shareholders to gain indirect exposure to VMware’s performance without Dell having to fully absorb VMware into its operations or issue separate VMware shares. It essentially tracked the economic performance of VMware without conveying direct ownership of VMware stock. The tracking stock kept VMware semi-autonomous while still providing Dell with cash flow benefits and keeping a stacke in VMware.

By the end of this, Silver Lake and Dell managed to pull off this epic acquisition. Mr. Dell, who continued as CEO of the company, and related stockholders owned approximately 70% of the pro-forma company common equity, excluding the tracking stock.

Divesture of SecureWorks

Roughly 6 months after the deal was closed and Dell, with EMC under its belt, just started seeing some synergies, the company divested one of its assets in one of the first tech IPOs of 2016.

SecureWorks, the cyber security division of Dell went public on Friday, April 22, 2016. That day, SecureWorks [NASDAQ: SCWX], priced its shares at $14 each. The stock opened slightly below that price at $13.89, which was down its initial pricing estimate, between $15.50 and $17.50 for its 9 million shares. It raised around $110m. SecureWorks had revenue of $339.5m and a net loss of $72.4m for the year ended January 29, Dell retained 86% of their stake in the company and 98% of voting rights.

The cybersecurity industry was growing rapidly in 2016, with increasing demand for services in response to rising cyber threats. By taking SecureWorks public, Dell aimed to capitalize on the growing investor interest in the cybersecurity sector, which could generate a favourable valuation.

The reason for the divestiture was mainly because of Dells acquisitions of EMC we had mentioned, since Dell raised over $50bn in cash for the deal the interest payments were getting expensive, and this would help lighten the debt burden. Dell also sold other parts of the business like its IT subsidiary Perot Systems for $3.1bn due to the debt burden.

Exiting the Investment

After a tenure of five years as a private company, Dell returned to the public markets in December 2018 in a near $24bn cash-and-stock deal. Instead of your traditional IPO, the company engaged in a complex financial manoeuvre where no new shares were issued to the public. This IPO involved the buying out of Class V shares, a tracking stock related to Dell’s 81 per cent stake in VMWare. Holders of these Class V shares were able to exchange their shares for either Class C common stock or $109 cash per share, a 29% premium.

A tracking stock is a special type of equity that tracks the financial performance of a specific segment or division of a particular company. These shares trade separately from the parent company’s shares on the market and allow investors to gain exposure to a high growth segment of the parent company.

Dell’s unique IPO allowed the company to simplify its capital structure into a dual-class share structure, with privately held Class A and Class B and publicly traded Class C shares. Both Michael Dell and Silver Lake retained control of the company through their Class B shares which contain super-voting rights. Dell’s public Class C shares opened at $46, marking a market valuation of $16 billion.

The $109 cash per share figure implies a pre-transaction equity value of $48.4bn for Dell, indicating that Silver Lake’s bet on the struggling company in 2013 massively paid off.

IPO – A new life

After five years in the private markets, Michael Dell was ready to return to the public eye. The take-private deal with Silver Lake had proven extremely beneficial for all stakeholders (except perhaps Carl Icahn). However, Dell’s IPO wasn’t straightforward and involved yet another sprinkle of financial engineering.

On December 28, 2018, Dell officially went public again on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker DELL. Dell was valued at approximately $16bn at the time, and its shares opened at $46 each. It went public via its clever tracker listing of DVMT, by buying back shares of the tracking stock rather than through a traditional IPO. Dell made an offer to DVMT shareholders, providing them with two options: a cash payment of $120 per DVMT share or Dell Technologies stock (1.3665 Class C shares for each DVMT share). The transaction was valued at $23.9bn, allowing Dell to consolidate ownership and retire the tracking stock. This move enabled Dell to avoid the traditional IPO process, which could have resulted in scrutiny over Dell’s $50bn debt.

Michael Dell and related stockholders retained 70% ownership of the company’s common stock.

Sale of crown jewels

Three years after Dell’s IPO, with the company valued at around $64bn, it was finally ready to sell its crown jewel. VMware, originally a subsidiary of EMC, became the key piece that allowed Dell to buy EMC and later served as Dell’s public listing vehicle.

VMware’s value had soared as cloud computing infrastructure became essential to IT departments worldwide. However, VMware’s listing stock was often undervalued compared to its actual worth, presenting Dell and Silver Lake with an opportunity. Dell spun off VMware, reducing its debt burden, but Michael Dell still retained a 42% stake in the company (worth about $25bn after the sale). VMware paid a special dividend to shareholders, amounting to approximately $12bn, to lighten Dell’s remaining net debt load, which stood at $32bn by July 2021.

On November 1, 2021, VMware paid a special dividend of $11bn to shareholders. The public received $2bn, while Dell, as an 81% owner of VMware, received $9bn. Using the dividend, along with $5bn in new debt, Dell bought back the tracking stock. The spin-off was completed through a special dividend of VMware shares distributed to Dell’s stockholders. After the spin-off, VMware stock rallied over 80%, giving Dell (without VMware) an implied market value of $33bn.

All of this financial engineering helped Michael Dell turn his $3.8bn interest in an out-of-favor PC maker into a personal stake in a broader data center hardware and software empire worth $40bn. Silver Lake’s gains on the VMware sale alone generated a 7.3x return on equity for one of its funds and 3.1x for another fund raised in 2018. While these moves might have benefited Michael Dell (nicknamed Mr. Denali) and Silver Lake the most, they also benefited all shareholders and demonstrated the power of financial mastery in transforming a struggling company

Conclusion

The Silver Lake and Dell saga illustrates a complex private equity deal that reshaped the tech industry landscape, cementing Silver Lake as a top-tier investor. Beginning with Dell’s challenges in a rapidly evolving market, the deal evolved through strategic negotiations that enabled the company to go private. The arrangement demonstrated the importance of private equity in fostering operational flexibility, which Dell capitalized on to focus on innovation and business transformation. Through various financial engineering maneuvers and strategic acquisitions, Dell was able to turnaround the business. Despite concerns from shareholders, the move proved crucial in realigning Dell’s business goals, setting a precedent for how private equity can reinvigorate established corporations in the technology sector.

1 Comment

Pietro Micelli · 9 October 2024 at 20:49

Great job. Article was extremely interesting. Well done!