Introduction

The evolution of Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) in Europe was shaped by the structural changes triggered by the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, when economic recession and slow judicial enforcement caused a drastic rise in impaired assets between 2008 and 2014. As outlined by the European Banking Authority (EBA), regulatory framework defines liability-exposures as “non-performing” in multiple instances. The “Past Due” category refers to loans with payments overdue by more than 90 days that exceed the minimum materiality threshold. Meanwhile, the “Unlikely to Pay” category classifies loans for which the bank believes the debtor is unlikely to meet obligations. Alongside these categories, “Bad Loans” refer to exposures subject to insolvent borrowers.

Highlighting their macroeconomic importance, NPL levels serve as a key indicator of their broader implications for the economy and the banking sector. A high volume of NPLs signals lower profitability for banks: as they suffer a decreased interest income and increased Loan Loss Provisions. In turn, this reduced profitability weakens capital buffers, lowering Tier 1 Capital ratios and limiting financial stability. As a result, banks take a more risk-averse approach and lower lending especially to small-medium size companies, reducing the money supply.

Understanding the outlook of NPLs in the European landscape requires an understanding of their evolution, securitisation mechanics and implications, factors explored through the specific case-studies of Greece and Italy.

Europe’s NPL Burden: From Peak to Resolution

In the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, European banks were left to deal with an unheard level of non-performing loans. Between 2008 and 2014, slow economic growth, weak supervision, and sluggish judicial systems led to a huge buildup of bad debt on balance sheets. By 2014, NPL ratios in a number of EU countries reached crisis levels, with Italy and Greece leading the charge.

This surge in NPLs created a systemic threat to financial stability which limited the ability of banks to lend, lowering their profitability. IMF research identified several transmission channels: lower profitability due to provisioning needs, higher funding costs, and increased capital requirements due to the risk weights applied to NPL exposures.

The trajectory of non-performing loans across the European Union from 2008 to 2025 reflects a decade-long structural deleveraging effort following the financial and sovereign debt crises. Immediately after the global financial crisis, the EU-wide NPL ratio rose quickly, going from around 2.8% in 2008 to a high of 7.5% in 2014. 2014 proved to be a turning point, when the ECB’s Comprehensive Assessment and Asset Quality Review led to more aggressive supervisory actions. By 2016, the NPL ratio was down at 5.4%, largely due to the emergence of national schemes such as Italy’s GACS and Greece’s HAPS. Further regulatory tightening, including “calendar provisioning” helped continue the decline in the EU-wide NPL ratio. By 2020, the average NPL ratio had fallen to 2.6%. According to the ECB, by Q1 2024 the EU-wide NPL ratio was at an all-time low of 1.7%, 75% lower than the value reported in 2014. In 2025, the ratio is currently at 2.2%.

Given the threat of persistently high NPLs, European institutions took a more active role after 2015. The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) led by the ECB resulted in more stringent guidelines on NPL classification, provisioning, and resolution. Additionally, the European Banking Authority (EBA) introduced a harmonized definition of Non-Performing Exposures (NPEs) under the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and CRD IV frameworks. Most importantly, the ECB also introduced “calendar provisioning,” requiring banks to fully provision unsecured NPLs within 2 years and secured ones within 7 years. This time-based approach incentivized rapid resolution or offloading of troubled assets. Moreover, national governments complemented regulatory reforms with bespoke schemes designed to facilitate off-balance-sheet NPL disposal through securitisation. These included Italy’s GACS in 2016 and Greece’s HAPS in 2019.

The lowering of bank balance sheets risk through securitisation and public-private risk sharing has helped strengthen the European banking sector. Capital ratios have improved, provisioning is now more proactive, and investor confidence has returned, resulting in a reduction in the cost of capital. However, these gains come with caveats. While banks have offloaded the NPLs, the risk has instead been transferred to investors, securitisation vehicles (SPVs), and servicers.

Italy’s NPL Crisis and the GACS Scheme

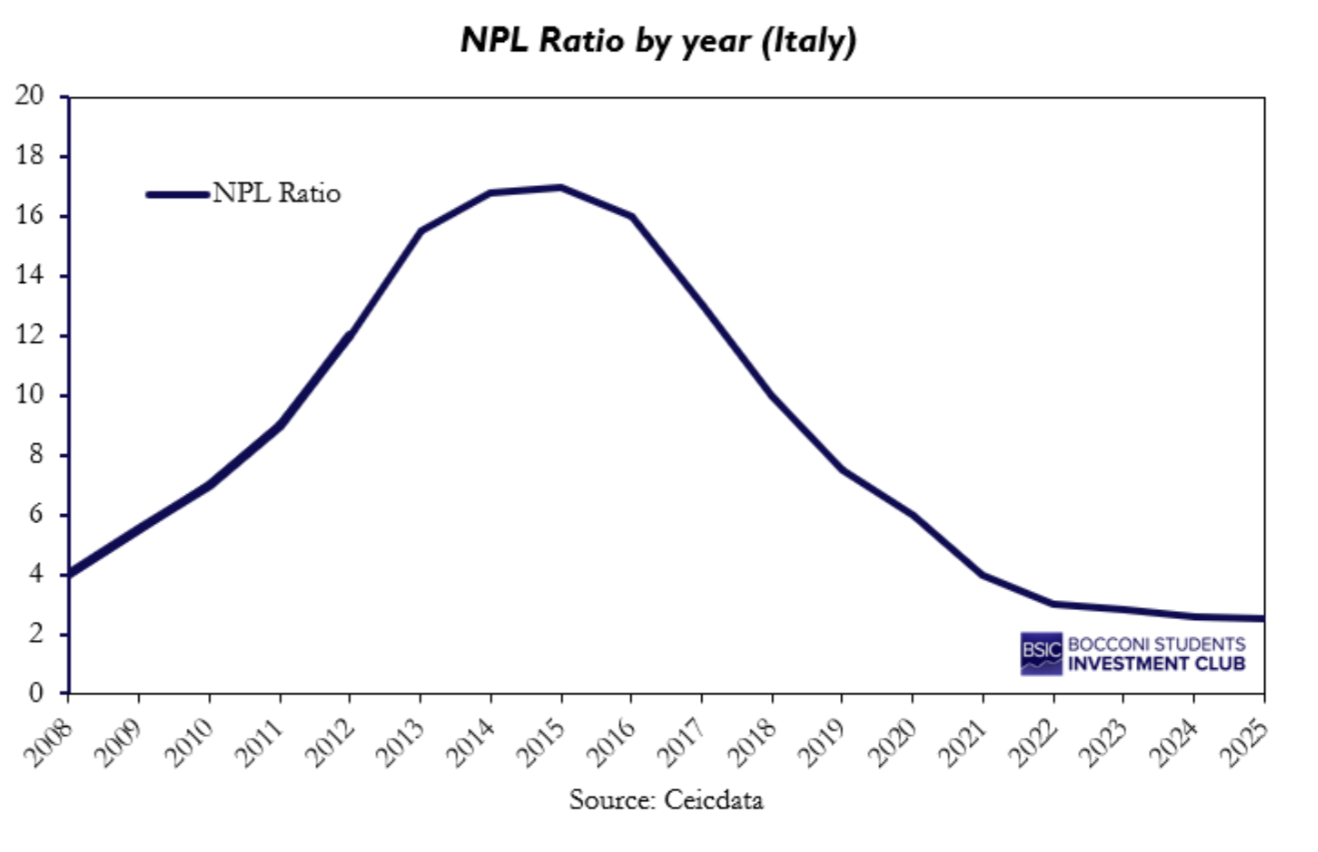

Following a prolonged period of economic crisis, Italy’s banking system was subject to high volumes of NPLs. This brought forward a rise in Italy’s NPL ratio, which built up to a peak of 17% in 2015, as reported below:

As a result, NPL volume implications damaged the profitability and stability of the banking system, reducing credit availability and economic growth. This prompted government intervention in 2016, enacted through the “Garanzia sulla Cartolarizzazione delle Sofferenze” (GACS), an initiative aimed at supporting the offloading of NPLs through securitisation.

As a result, NPL volume implications damaged the profitability and stability of the banking system, reducing credit availability and economic growth. This prompted government intervention in 2016, enacted through the “Garanzia sulla Cartolarizzazione delle Sofferenze” (GACS), an initiative aimed at supporting the offloading of NPLs through securitisation.

In fact, each transaction involved the creation of a special-purpose vehicle (SPV), which recorded the NPL portfolio into its books and financed it through the issuance of debt tranches. By selling these loan portfolios to SPVs, banks were able to transfer the associated risk and derecognize the NPLs from their balance sheets. This transfer implied banks could reduce their Risk Weighted Assets (RWA), improving their Tier 1 Capital ratio and subsequently enhancing loan availability. Over time, this framework partially deflated the NPL ratio that fell from 16% in 2016 to 2.5% in 2025, enabling an exit from Italy’s “NPL Crisis”.

To attract investors towards these securities, the Italian government introduced a guarantee mechanism to GACS, compounding on its effect. The scheme promised a sovereign guarantee on the senior tranches of these securities, representing the sections of NPL transactions with the lowest risk and yield. As a result, the senior tranches could be issued with investment-grade ratings, facilitating market placement. The boosted attraction towards NPL investing is exemplified by the €108.6 bn securitised by banks between 2016 and 2022, with guarantees still outstanding despite the GACS’s expiry in June 2022 and no state payouts having been called. Further considering regulatory standards, the initiative also included a fee, which banks were required to pay, as a reflection of market conditions, in order to conform to EU rules. To price this fee, the scheme considered the average spread of Italian credit default swaps (CDS) for different maturities, a precise reflection of the weighted average life of the senior-tranche notes. This pricing system ensured competition remained neutral and allowed for an accelerated disposal of NPLs without a state subsidy.

Overall, the GACS scheme, honed with an effective regulatory system, enabled the Italian banking system to escape its NPL crisis, leading to positive implications on the country’s economic growth, through an improved money supply and financial stability.

Greece’s NPL Odyssey and the Hercules (HAPS) Scheme

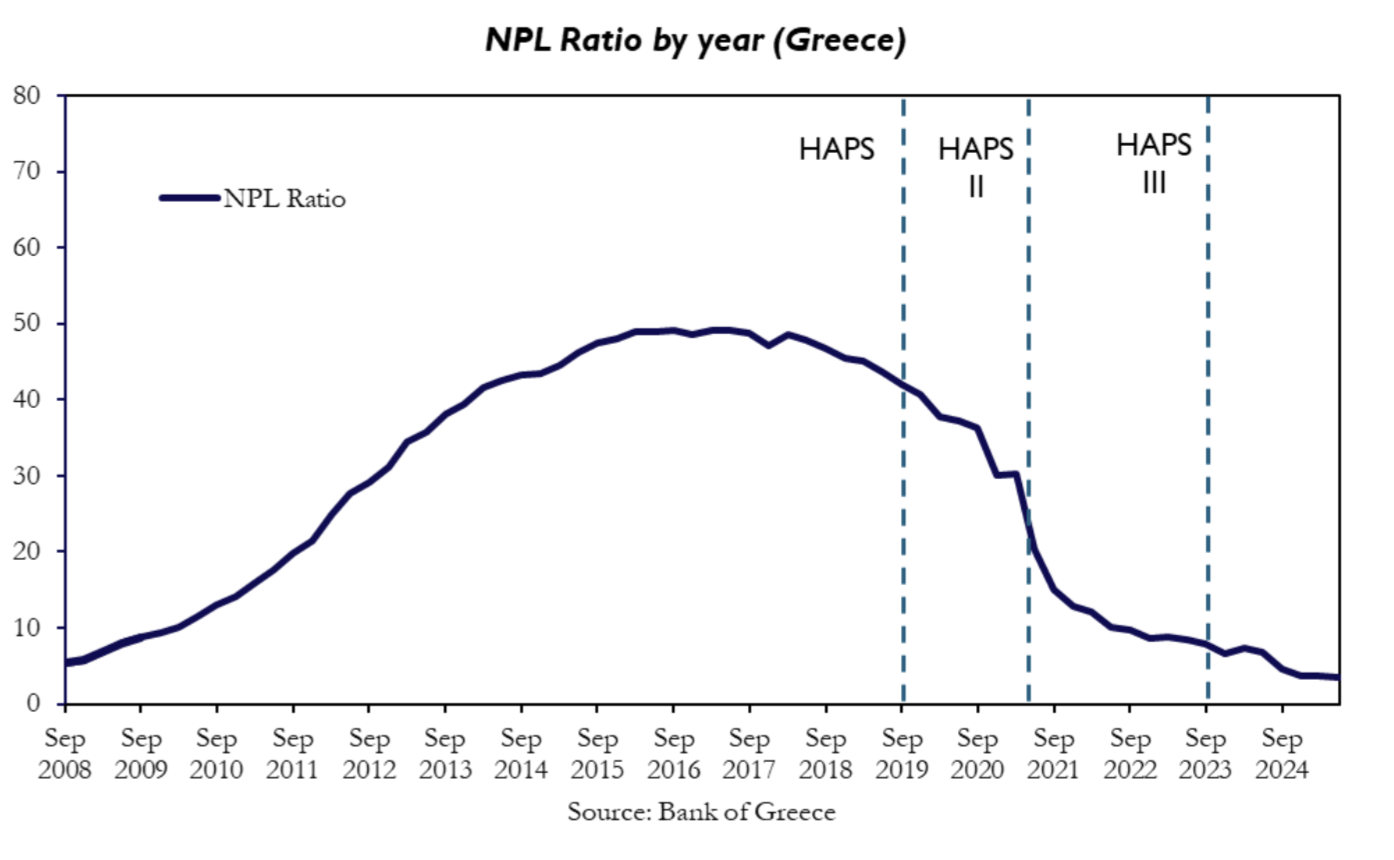

Greece’s banking crisis was even more severe, with NPL levels among the highest ever seen in the eurozone. By 2016, Greek banks’ NPL ratio had skyrocketed to 49% – nearly half of all loans were non-performing during the worst of the Greek debt crisis. This was clearly unsustainable, crippling banks and the economy. After some initial ad-hoc sales and write-offs, Greece launched its comprehensive NPL resolution program in 2019 with the Hercules Asset Protection Scheme (HAPS), nicknamed “Project Hercules.” HAPS was closely modelled on Italy’s GACS, adapting the concept of state-guaranteed NPL securitisations to Greece’s context.

Like GACS, Hercules provides an irrevocable state guarantee on senior tranches of NPL ABS deals, on the condition that the selling bank offloads enough of the risk (mezzanine and junior notes) to outside investors. Greek Law 4649/2019 set up HAPS initially for an 18-month period, later extended as Hercules II and Hercules III in successive years as the banks continued to deleverage. Under HAPS, banks could bundle their bad loans into securitisations and purchase the government guarantee for a fee (pricing tied to Greek CDS spreads, to satisfy EU state-aid rules similar to GACS). The structure of each deal is essentially the same as described for Italy’s deals. One requirement unique to Hercules is that at least 50% + 1 of the mezzanine and junior notes must be sold to non-bank investors for the guarantee to apply. This ensures the bank truly transfers risk and is not just keeping the risk in disguise.

The Hercules scheme enabled Greece’s four systemic banks (Alpha, Eurobank, NBG, Piraeus) to execute massive NPL securitisations between 2019 and 2022. In total, 17 securitisation transactions with a gross book value around €50–€55bn were completed under HAPS I and II. (HAPS III, a further extension into 2023–24, was aimed at smaller banks and any remaining portfolios.) The results have been dramatic. Greek banks’ average NPL ratio plummeted from over 40% in 2019 to single digits by 2022. By Q3 2022, the aggregate NPL ratio fell to 9.7%, and as of Q1 2024 it improved further to 7.5%. The largest banks now report NPL ratios in the low single digits (around 2–5%), comparable to European peers. This is a staggering turnaround from the dark days of 2015–2016. In terms of NPL stock, Greek banks have slashed bad debt volumes from over €100bn at peak to roughly €6bn by 2025 – about an +€95bn reduction in bad loans outstanding.

However, as in Italy, shifting NPLs off books does not mean they disappeared. In Greece, the bad loans were largely transferred to credit servicing firms (CSFs) and securitisation SPVs, which are now tasked with recovering value from those loans. By early 2024, about €70bn in loans (down from a €87.7bn peak) were under management by CSFs, working through courts, restructurings, and collections. The Hellenic Financial Stability Fund and regulators remain vigilant that these servicers continue to work through the backlog. The Hercules scheme was recently reintroduced for a final one-year extension (end-2023 to end-2024) with a limited guarantee budget, mainly to cover any residual NPL cleanup and include some smaller banks. By 2025, with the bulk of legacy NPLs addressed, Greece’s focus is shifting to preventing new NPL formation and resolving the remaining distressed assets outside of banks.

In summary, Hercules (HAPS) has been Greece’s equivalent of Italy’s GACS – a “bad loan insurance” program that enabled a very successful reduction in NPLs. The country’s banking system is far healthier now: for the first time since the debt crisis, Greek banks can operate with normal levels of bad loans (close to EU average) and have returned to profitability and lending growth. As the program winds down, the remaining challenge is ensuring the ongoing recovery of the securitised loans by the servicers.

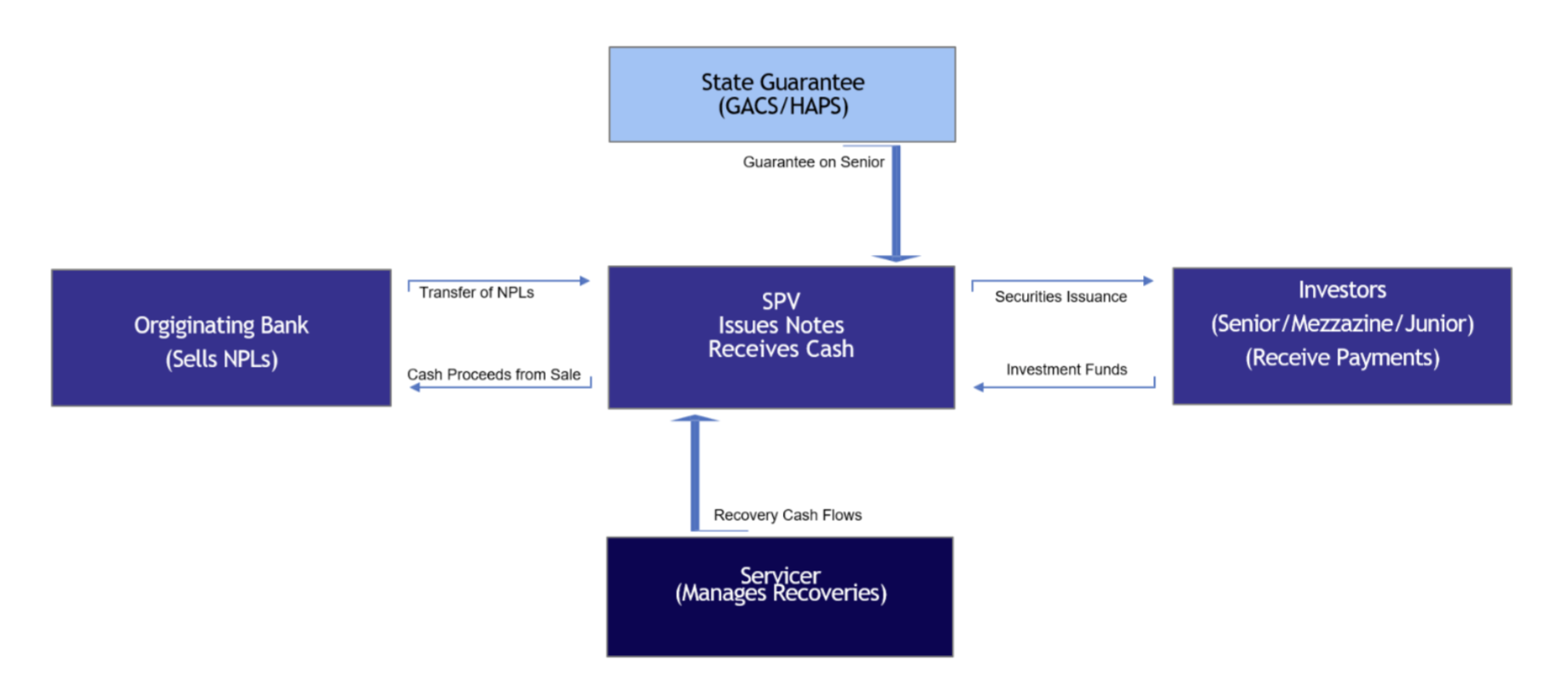

Securitisation Mechanics & Bank Exposure

In a typical GACS or HAPS transaction, the bank (the originator) sells a portfolio of non-performing loans to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) specifically created for the securitisation under the relevant legal framework in Italy this is coordinated by Law 130/1999. The sale is structured as a “true sale,” meaning that both the legal and beneficial ownership of the loans is transferred to the SPV, ensuring the so-called “bankruptcy remoteness” of the assets. Once the loans are transferred, the SPV finances their purchase by issuing asset-backed securities (ABS) to investors. These securities are divided into tranches according to their risk profile: the Senior tranche, which benefits from a state guarantee and is the least risky; the Mezzanine tranche, which carries intermediate risk; and the Junior tranche, which absorbs the first losses and offers the highest potential returns. The average structure of these deals has been approximately 85% Senior, 10% Mezzanine, and 5% Junior.

The recoveries from the underlying loan portfolio are managed by a servicer, often specialized in distressed debt management. The servicer collects payments, manages legal enforcement, and oversees asset disposals, distributing the proceeds through a “cash flow waterfall” mechanism: first, operational costs and servicing fees are covered; then interest and principal on Senior notes are paid; subsequently, Mezzanine noteholders are paid; and finally, any residual cash flow is distributed to the Junior tranche. The state guarantee applies exclusively to the Senior tranche and can be invoked only if recoveries fall short and senior payments are not met.

Significant Risk Transfer (SRT) and Bank Exposure

A key regulatory feature of these transactions is the concept of Significant Risk Transfer (SRT), as defined under the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and the Securitisation Regulation. For a securitisation to achieve off-balance-sheet treatment, the originating bank must transfer a substantial portion of the credit risk to third-party investors. At the same time, the bank must retain at least 5% of the securitised exposure known as “skin in the game” to ensure incentive alignment. In practice, banks often retain the senior guaranteed notes, which represent a low-risk asset thanks to the state guarantee but still remain partially exposed to the underlying recovery performance, by doing this the bank achieves both balance sheet deconsolidation and capital relief while maintaining a limited exposure linked to the guaranteed asset.

The economic rationale behind these structures is straightforward. By securitising NPLs, banks can reduce their risk-weighted assets (RWA) and improve key regulatory capital ratios, such as the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio. The sale of NPL portfolios also provides immediate liquidity, which can be used to deleverage or reinvest in core business activities. Moreover, the state guarantee on the senior tranche enhances investor confidence, narrowing the bid-ask spread between banks and buyers and increasing the volume and pricing efficiency of NPL transactions. The result is a more active and transparent secondary market for distressed assets by standardizing transaction structures, improving information disclosure, and aligning incentives between originators, servicers, and investors, GACS and HAPS have transformed what was once an opaque, illiquid market into a more accessible asset class.

Valuation Drivers and Recovery Dynamics

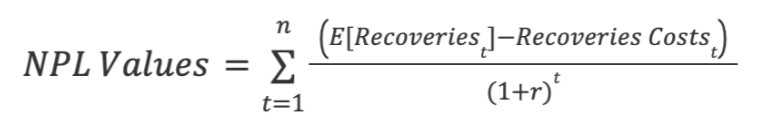

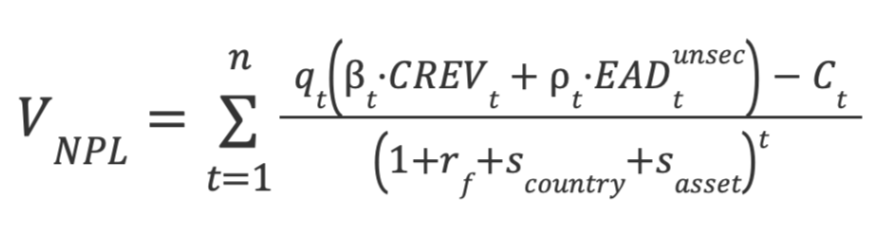

The valuation of Non-Performing Loans depends on several interrelated drivers that determine the expected recoveries and the price investors are willing to pay. The first and most important factor is the quality and type of collateral securing the exposure. Secured loans backed by real estate, especially residential or prime commercial properties, are generally valued higher than unsecured or corporate loans. The Capped Real Estate Value (CREV) represents the main reference for estimating recoveries and is defined as the minimum between the Real Estate Value (REV), the most updated appraisal of the collateral, reflecting its condition, occupancy, and location, and the Outstanding Loan Amount (OLA). This ensures that recoveries do not exceed the lower of the property’s value or the debt owed. The Gross Book Value (GBV) instead indicates the nominal exposure before provisions and serves as a reference for calculating the haircut applied by the market. The relationship between these three indicators defines the expected recovery ratio and helps determine the degree of discount an investor will demand.

Another key variable is the recovery horizon since the longer it takes to complete legal or extrajudicial procedures, the lower the present value of recoveries. In Italy judicial enforcement can often exceed eight years and this time factor has a direct effect on valuation because the expected cash flows must be discounted over a longer period. The probability of default and the expected loss given default also play a crucial role since the risk that the borrower or guarantor will not fully repay the debt must be incorporated into the model. Under IFRS 9 the expected loss is estimated using forward-looking assumptions for probability of default (PD), loss given default (LGD), and exposure at default (EAD) across the lifetime of the loan. The discount rate used to bring expected cash flows to present value reflects both market risk and the perceived uncertainty of recoveries. Because the NPL market is illiquid and lacks a measurable beta, the discount rate is not derived from CAPM but from investors’ target returns and is influenced by the country risk premium, the type of debtor, the collateral characteristics, and the geographical location of the asset. Higher risk loans such as unsecured corporate exposures in southern regions are discounted at higher rates than secured residential mortgages in northern areas.

Finally, the valuation must consider the efficiency of local courts, the competence of the servicer, and all legal and administrative costs that reduce the net recoverable amount. In essence, the value of an NPL corresponds to the present value of expected recoveries net of costs, where recoveries are driven by collateral value and type, default probabilities, and the expected recovery horizon. The combination of these elements explains why a persistent gap exists between the book values recorded by banks and the market prices offered by investors, as the latter apply higher risk-adjusted discount rates to reflect uncertainty, illiquidity, and the complexity of the Italian recovery process.

Servicing & Collection Performance – The Weak Link

Europe has done the heavy lifting on structuring and placing NPL risk; the open question is execution. Every securitisation launches with a detailed Business Plan (BP) that sets a glide path for cash collections and, by extension, the deal’s economics: tranche sizing, pricing, and hard-wired performance triggers for fees and coupons. A few years in, the pattern is consistent across Italy and Greece: early vintages, in particular, are tracking below plan. Some of that is mechanical (COVID-era court bottlenecks, sluggish auctions, higher discount rates), some of it is modelling optimism, and some is simple maturation – the “easy” cases clear first, leaving harder recoveries to the tail. The result is familiar: cumulative collections slip under targeted thresholds, and servicers are forced into more active portfolio management to defend covenants.

In practice, a servicer has three levers. The first is judicial enforcement and liquidation – foreclosures, bankruptcies, court-supervised sales, REO conversion. It carries the highest certainty once executed, but it is slow, procedural, and cost-intensive, and depends on court throughput and bidder depth. The second is out-of-court resolution -consensual workouts such as discounted pay-offs, reschedulings, and debt-to-asset/equity solutions. This is faster and cheaper when borrower incentives align, but it is sensitive to the interest-rate backdrop and counterparty willingness. The third is asset and portfolio trading – selling loans, carved-out sub-pools (e.g., unsecured tails or regionally concentrated SMEs), or even note positions to a specialist who can extract value differently. This last lever is the one you pull when the priority is cash now to protect BP ratios.

Where you sit in the capital stack largely explains your behaviour. Senior notes are the safest slice: they get paid first, are protected by the subordination of the other tranches and, under GACS/HAPS, benefit from a sovereign guarantee. They are meant to be boring. Mezzanine is where most global credit funds (Cerberus, Bain Capital, DK, Elliott, etc.) take risk. Their returns live and die by staying on (or above) the Business Plan: miss interim targets and interest can be deferred; beat the plan and delever faster, and the IRR steps up. Junior/equity is the first-loss piece, typically held by the sponsor/servicer to align incentives; it has the biggest upside and the widest dispersion of outcomes.

Servicer is appointed at closing. The originator proposes the servicer, but investors and rating agencies require capability, independence, and hard service-level agreements (SLAs) before the deal prints. Once the structure is live, control rights – amending the BP, approving bulk sales, or even replacing the servicer – sit with noteholder governance. In practice, once seniors are adequately protected, mezz and junior tend to have the louder voice on strategy, because that is where the economic risk really sits.

When performance weakens, the triggers are mechanical. Fall below, say, ninety percent of cumulative BP and the waterfall reconfigures, variable servicer fees are deferred or pushed down the stack; mezzanine coupons are switched off or subordinated behind principal to accelerate senior amortization; persistent breaches can lead to servicer replacement. To avoid that cascade, sponsors, and servicers reach for the third lever – sell. That typically means bulk disposals of slower or litigation-heavy clusters, regional carve-outs, or note-level sales. The trade-off is explicit: surrender some long-tail optionality to pull cash forward, lift the cumulative ratio back above the line, preserve fee economics, and keep structural optionality intact. This is precisely what is feeding a secondary pipeline.

Results and Outlook

Both Italy’s GACS and Greece’s HAPS have proven to be highly effective public–private schemes for tackling the legacy NPL overhang that followed the financial and sovereign-debt crises. Crucially, both frameworks were structured so that the state guarantee was provided at market terms and funded by the issuing vehicles, ensuring that banks bore the cost rather than taxpayers. Under GACS, banks purchased the Italian Treasury’s guarantee on senior notes at prices linked to Italian sovereign CDS spreads, while HAPS applied a similar fee-based structure backed by collateral rather than direct public outlays. In this way, both programs enabled a large-scale transfer of NPL risk from bank balance sheets without requiring public bailouts or fiscal intervention.

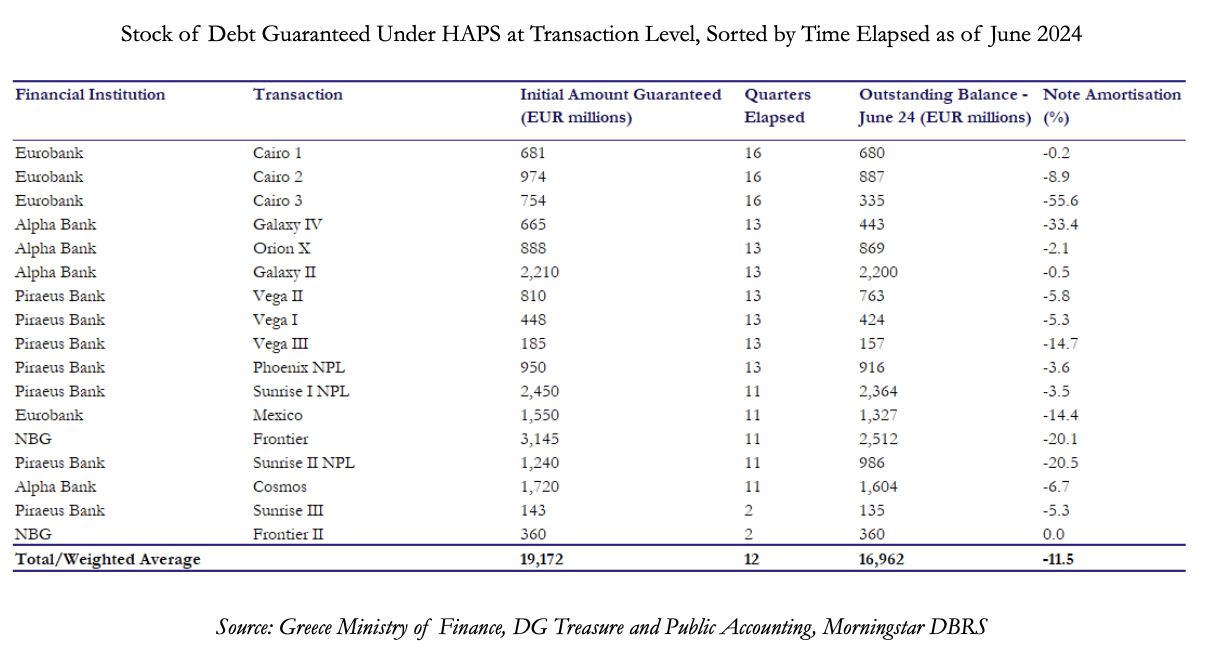

At the same time, it is clear that collections on the securitised NPL portfolios have generally fallen short of original business plans. In Greece, HAPS performance data paints a picture of persistent timing tension and collection lag. By June 2024, the amortisation of senior notes guaranteed under HAPS amounted to only €2.2bn, a modest 11.5% reduction from issuance across 17 transactions – even after three to four years of seasoning. Several deals still stand at low single-digit amortisation, clear evidence that the majority of business plans remain far from worked out. The overall stock managed by Greek credit-servicing firms is still sizable, sitting at around €70bn nominal, down from a peak of €87.7bn (2022). In Italy, official reviews have also found a substantial share of early GACS transactions lagging their projected recoveries: one Treasury report noted that about 19 of 33 GACS securitisations were underperforming their business plans, in some cases collecting less than half the targeted amounts.

Overall, however, the evidence supports the view that both GACS and HAPS largely achieved their principal goals. They allowed banks to deleverage massive NPL stocks and return to much sounder footing without needing taxpayer-funded bailouts. Going forward, ongoing market activity (new trading of loan portfolios and securities) is aimed at closing the remaining gap between projections and actual recoveries, reflecting a realistic adjustment of expectations rather than a failure of the schemes’ original objective.

0 Comments