Introduction

“Let it grow, let it grow, let it grow” – The Lorax

The fundamental idea behind every profit-seeking firm is to take an initial investment and multiply it. One of the first challenges any daring entrepreneur must face on their journey towards unicornhood is how to secure this initial investment, or in other words, what to give up. Debt financing constrains flexibility while Equity financing dilutes control. In capital-intensive industries, these constraints may become untenable. Royalty-Backed Financing seeks to combine aspects of both debt and equity financing to create a suitable alternative. With upside akin to equity and clearer revenue streams, comparable to those of debt, lenders are enticed to provide liquidity to firms using this strategy. In this article, we will explore the mechanics of royalty-based financing, the underlying effects on the firm, the criteria for suitability, and various examples.

Mechanics of Royalty-based Financing

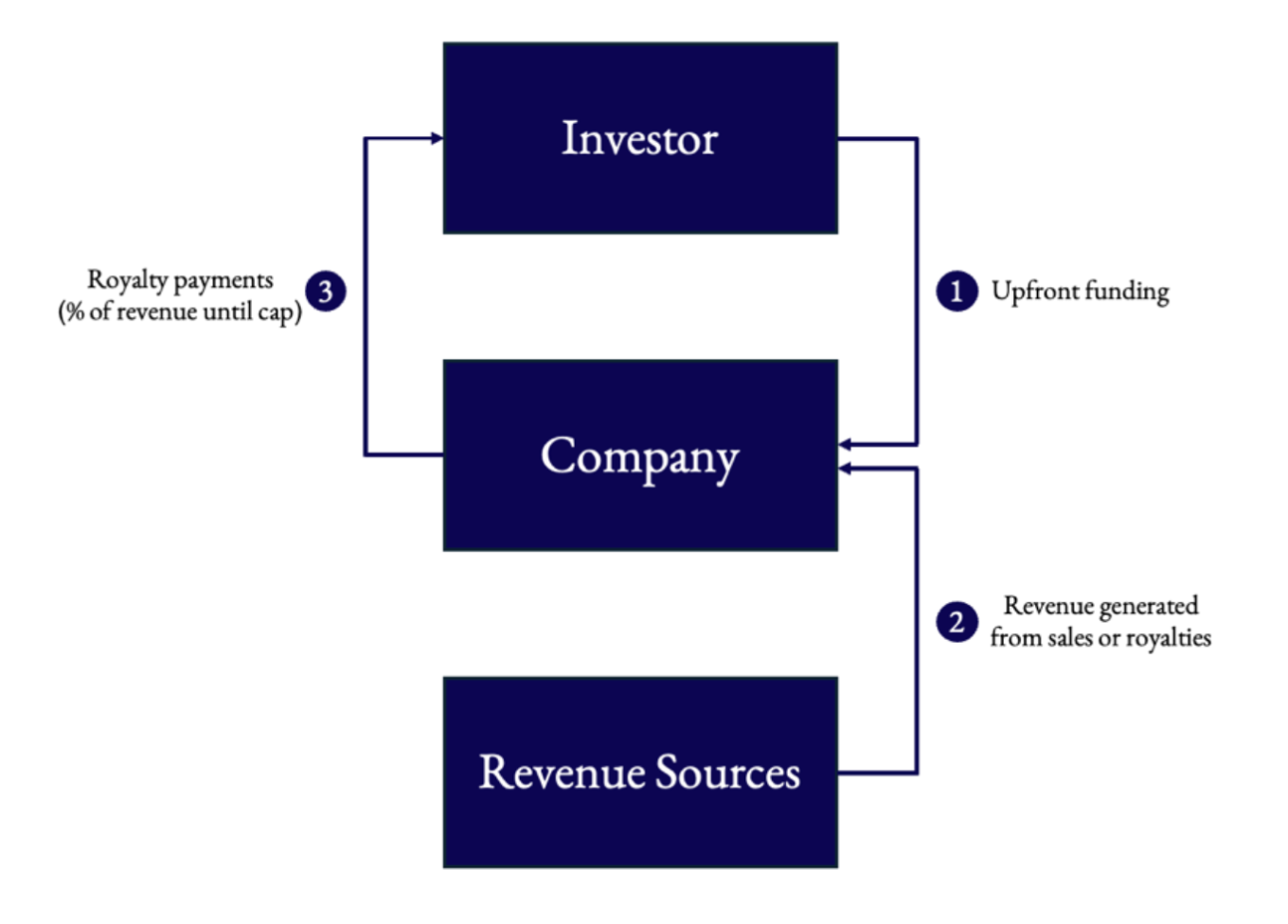

Royalty-based financing (RBF) is an alternative funding method in which a company receives capital from an investor in exchange for a percentage of future revenues (royalties). Instead of fixed interest payments, as in traditional loans, or giving up ownership, as in equity financing, the company pays the investor back through a “pay-as-you-earn” model. Payments thus rise and fall with the company’s performance. In high-revenue periods, the investor is paid back faster, while during downturns, the payment burden falls. This flexibility makes RBF suitable for companies with variable or growing revenue streams.

A key feature of RBF is its non-dilutive nature. The company does not issue new shares, as founders and existing shareholders retain control of equity and voting power. This contrasts with equity financing, where raising capital means selling a portion of the company and accepting dilution, often resulting in greater investor influence over governance. RBF investors, however, have no equity claim on residual profits beyond the agreed royalty, and typically do not receive board rights.

RBF also differs from conventional debt. Traditional loans require fixed repayments, regardless of revenue, which can strain cash flow and increase insolvency risk. In RBF, payments vary with revenue, so typically, there are no fixed installments. If revenue is low, payments are low, and if revenue is zero, payments may be zero for that period. As RBF agreements are either unsecured or primarily secured by the revenue stream and often avoid a personal guarantee, investors bear greater risk. Therefore, repayment is typically structured so that the investor receives more than the original amount advanced. In that sense, RBF combines features of both debt and equity.

An RBF contract is defined by key parameters. The royalty rate (percentage of revenue paid) determines the short-run cash-flow burden, and the repayment cap (or multiple) determines the investor’s total upside. Many deals also specify a term or maturity date, sometimes with a balloon payment or buyout option if the cap is not met by a given time. Another important aspect is how revenue is defined. It may refer to gross sales, sales net of refunds, or only certain products and channels. The agreement will further specify reporting frequency, audit rights, and payment timing. Finally, the contract also determines payment priorities, including whether royalties are paid before or after other obligations and whether the investor holds security interests in specific assets.

There are several ways to structure RBF deals. The following are three common structures:

There are several ways to structure RBF deals. The following are three common structures:

Secured Loans Against Royalties: The company borrows money against a specific royalty or revenue stream, often tied to a product or IP. The lender is repaid from that stream, usually through a percentage of sales or licensing income, until a cap is reached.

Pros: relatively straightforward, non-dilutive, and often quicker to execute. Repayment is tied to a specific royalty stream, which helps to keep the claim focused on that cash flow rather than the entire business.

Cons: often expensive and may still count as debt for leverage metrics. Underperformance can lead to an extended repayment period, with the lender retaining rights to the collateral. Firms choose this structure when they have a clearly identifiable revenue stream and want quick execution.

IP HoldCo and License-Back: In this structure, the firm transfers selected IP, such as trademarks or patents, to a separate holding company (HoldCo) funded by the investor. The operating company then licenses that IP back so it can continue using it in business. The ongoing license payments are what generate returns for the investor.

Pros: raises non-dilutive capital and may avoid adding conventional OpCo debt. License payments are often tax-deductible expenses, and some agreements give the firm the right to buy the IP back once the investor has earned the agreed return.

Cons: legally complex and can restrict crucial IP. If payments fail, a firm’s control of IP can be at risk, and future financing flexibility may decline. Firms usually choose this approach when their IP is valuable, but borrowing capacity is constrained.

Securitization of Royalties: The company converts a stable royalty stream into an asset-backed security sold to investors. Typically, a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) acquires the royalty rights and issues notes to investors. The royalties are then collected by the SPV and used to pay interest and principal.

Pros: can provide large upfront capital, and, for predictable cash flows, it can be priced relatively cheaper than other forms of financing

Cons: complex and costly to arrange, requires scale and disclosure, and gives up future income and flexibility from the securitized royalties until investors are repaid. Firms choose securitization when royalties are backed by strong contractual terms, diversified, and suitable for institutional investors.

Advantages and Disadvantages for the Firm

RBF can be an attractive option for some firms, but its impact depends on the reliability of the royalty stream, the business’s margins, and the agreement’s structure.

Advantages of RBF for firms include:

Non-Dilutive Capital: RBF provides funding without giving up equity ownership. This preserves founders’ and existing shareholders’ stakes and avoids shifts in governance. This is attractive when equity would be raised at an unfavorable valuation or when management prefers to avoid investors focused on a near-term exit.

Flexible Repayments: As payments vary with revenue, RBF can reduce the financial strain during downturns. The firm is not forced into fixed payments that could result in cuts in payroll, inventory, or marketing when revenue falls. This can support smoother cash-flow management, which is particularly valuable for seasonal or volatile businesses.

Alignment of Incentives and Limited Interference: RBF links the investor’s return to performance, so both parties benefit from revenue growth. Furthermore, compared with equity investors, royalty investors typically do not demand board seats or control rights. This allows management to retain strategic autonomy while still obtaining growth capital, which is attractive for firms that want to scale quickly without diluting ownership.

Access to Funding when Traditional Channels are Limited: Some firms use RBF because they do not meet bank lending criteria or do not want to dilute equity. RBF can monetize contracted royalties or product sales even if reported earnings are reduced by reinvestment. In more distressed situations, it may provide liquidity without immediately forcing a full restructuring, provided the royalty burden remains sustainable and does not destabilize operating cash flows.

Disadvantages of RBF for firms include:

High Implicit Cost of Capital: The most common critique of RBF is the cost. The agreed revenue share and repayment multiple can translate into a high effective IRR, particularly when the business performs well, as strong revenue growth can accelerate repayment and increase the investor’s realized return. As a result, the company may end up paying a large total amount relative to the upfront capital received.

Limited Upside Retention: A related issue is how RBF affects the firm’s cash flows during its strongest periods. Because payments are tied to revenue, the company continues to share a portion of sales precisely when demand is highest and internal reinvestment opportunities are most attractive. This can make financing feel restrictive, even if the cost is acceptable, because the obligation acts like a continuing claim on revenue until the cap is reached. Unlike a fixed-rate loan that can be refinanced or retired early without an ongoing revenue share, RBF scales automatically with sales. Some contracts allow buyouts or early termination, but these are typically priced to protect the investor’s expected return.

Potential Loss of Intellectual Property: Depending on how the deal is structured, RBF may expose intellectual property to risk. In arrangements where IP is pledged as security or moved into an IP holding company, missed payments can ultimately lead to the investor gaining control over key trademarks or patents. Even if the company performs and never defaults, the IP is still restricted. This can make it harder to raise additional financing and limit the firm’s ability to sell or reorganize assets.

Constraints on Future Financing and Operating Flexibility: While RBF can be flexible in how repayments adjust with revenue, the contracts themselves may still include limitations. To protect the royalty stream, investors often require regular reporting and audit rights, and they may restrict the company’s ability to take on additional secured debt. In some cases, agreements also include operational protections, particularly if those directly affect sales. These provisions do not eliminate RBF’s cash-flow flexibility, but they can reduce the firm’s operating flexibility.

Overall, these points show that RBF works best when a company has a reliable, diversified royalty stream and enough margin to support an ongoing revenue share. In those cases, it can provide non-dilutive capital with repayments that adjust to performance. However, if the royalty base is uncertain or highly concentrated, it can quickly become costly and could limit the firm’s future flexibility.

Criteria for RBF as a Suitable Financing Strategy

Royalty-based financing is most effective when a company’s revenue can comfortably sustain varying, sales-linked obligations while maintaining long-term growth. This means the business generates relatively predictable and recurring revenues, supported by contracts, subscriptions, licensing agreements, or other methods that provide transparent future cash flows. Since investors are repaid directly from top-line performance, stability and diversification of revenue sources are essential to making the structure work. Companies with strong unit economics are particularly well-suited. When gross margins are high and sales generate meaningful contribution profit, a percentage-based repayment can be absorbed without reducing the money available for reinvestment in growth.

RBF can also be attractive for firms that want to raise capital for growth but do not want to give up shares or decision-making power. The structure does not require the issuance of new shares, allowing existing shareholders to avoid dilution. It therefore becomes relevant when the company is believed to be undervalued, or an improvement in performance may boost valuation later. Businesses built around intellectual property, such as branded products, patented technologies, media catalogues, or franchises, are also relevant. They can often isolate specific revenue streams and monetize them efficiently. When those cash flows are transparent and documented accordingly, a revenue-based arrangement can be put in place. Therefore, liquidity can be provided while broader operations remain intact. Sometimes royalty-based financing can also be applied to firms that cannot easily access traditional bank debt due to accounting losses or heavy reinvestment, but still demonstrate a strong outlook and credible growth prospects.

The same features that give RBF flexibility also make it problematic when conditions aren’t as favourable. If a company is experiencing a structural revenue decline due to factors such as competitive pressure or regulatory shifts, committing to a revenue share agreement can place greater financial strain on the company. Payments are calculated as a percentage of sales rather than profits, leading to liquidity pressure for firms with volatile or thin margins during periods of inflation or underperformance. Businesses with high fixed operating leverage are particularly exposed, as a decline in revenue may simultaneously reduce cash flow from operations.

The risk is also increased when revenues are highly concentrated, such as with a small number of customers or products. In those cases, disruptions, such as the loss of a key contract, can impair the company’s ability to repay its royalty obligations. A financing structure that reallocates cash flows in a way that disadvantages existing lenders may also cause conflicts and potential creditor disputes. In addition, if financing agreements require the company to pledge intellectual property or allocate specific revenue streams, flexibility can be limited. Future refinancing, additional borrowing, or corporate transactions may become more complicated if key assets or cash flows are already tied up.

While royalty-based financing avoids equity dilution, it may still be expensive. The effective cost of capital can be significant, especially with quickly growing revenues. RBF can pose a costly alternative to other financing methods, particularly if lower-cost senior debt or attractively priced equity is available.

Overall, royalty-based financing works best for companies with stable, diversified revenues, strong margins, and clear growth, especially when combined with a strategic preference to retain ownership and operational control. It becomes considerably less attractive when revenues are unstable, margins are insufficient, or the structure restricts future financial and strategic flexibility.

Case Studies

Mitchells & Butlers: Long-Running Whole-Business Securitisation Under Structural Pressure

Royalty-based and whole-business securitisation structures have produced some of the most striking examples of both financial engineering success and long-term constraint. The experience of Mitchells & Butlers (M&B) illustrates how such structures can endure but also become a structural burden. In 2003, the UK pub operator entered into a landmark whole-business securitisation, pledging the cash flows of a large pub estate to raise long-term funding. The structure provided access to attractively priced, long-dated capital backed by predictable pub-level cash flows from rent, drink sales, and food revenues, which at the time appeared resilient. The deal was large enough to lead to imitation across the sector. However, those seemingly stable cash flows proved more volatile over time. Impacted by smoking bans, shifting drinking habits, the global financial crisis, and later the Covid-19 pandemic, revenues began to erode. Although the securitisation did not collapse outright, it locked substantial assets into a ringfenced structure. Even as debt amortised, the estate remained pledged, reducing financial flexibility and complicating strategic manoeuvring. The case demonstrates that whole-business securitisations can provide stable, low-cost funding when cash flows are steady, but they can also become rigid and inefficient in industries subject to long-term structural change.

Domino’s Pizza & Dunkin’ Brands: Franchise Systems Where It Worked

By contrast, franchise-heavy quick-service restaurant chains often represent the “textbook” success case for whole-business securitisation. Domino’s Pizza has repeatedly issued securitised notes backed by franchise royalties and supply-chain revenues through bankruptcy-remote entities. Because its model relies on thousands of franchisees paying contractual royalties and purchasing through a centralised distribution system, cash flows are diversified and highly predictable. This stability has enabled Domino’s to obtain investment-grade ratings on portions of its securitised debt, reduce its weighted-average cost of capital, and refinance opportunistically. Dunkin’ Brands followed a similar approach, securitising franchise fees and IP-related revenues prior to its sale to Inspire Brands. In these examples, the structure worked largely as intended: it monetised stable royalty streams at relatively attractive rates while preserving operational control. The key difference relative to M&B lies in the resilience and geographic diversification of franchise-based cash flows.

Hooters & TGI Fridays: When the Structure Becomes a Constraint

Even within franchising, outcomes can greatly vary. Hooters used a whole-business securitisation backed by franchise and licensing income, but a steadily declining operating performance made the structure a constraint. While revenues weakened, the rigidity of covenants and the complexity of multiple bond tranches complicated restructuring efforts. TGI Fridays encountered similar challenges: declining sales and operational underperformance made it harder to sustain the securitisation framework, contributing to financial distress. Since securitisation assumes regularity in cash flows, when that assumption breaks down, the structure can amplify stress rather than absorb it, showcasing one of the main issues.

IP HoldCo & License-Back Structures: Strategic Flexibility or Controversy

A different methodology, the IP HoldCo and license-back structure, is evident in transactions such as J.Crew’s controversial 2016 transfer of intellectual property into a separate, unrestricted subsidiary. Although not a classic growth-oriented RBF, the move effectively ringfenced brand IP away from certain creditors and enabled new financing secured by those assets. While it provided short-term liquidity, it triggered litigation and became an example of aggressive liability management. In more stable settings, IP HoldCo structures have been used more constructively. For example, pharmaceutical companies have sold royalty interests in drug portfolios to specialised investors such as Royalty Pharma. In those transactions, future drug royalties are monetised upfront while the operating company retains commercial control. When the underlying products remain successful and patent protection holds, the arrangement functions smoothly. However, if clinical risks materialize or patents expire earlier than anticipated, royalty monetization may become expensive relative to the upside the company would otherwise have retained.

Secured Royalty Loans: Music Catalogues and Revenue Disruption

Secured royalty loans against specific assets represent a more focused form of RBF. Music catalogue transactions provide a useful illustration. Artists such as David Bowie were the first ones to securitize future royalty streams (the “Bowie Bonds”), raising upfront capital against predictable music revenues. Initially, it was considered innovative and successful, while the bonds were later downgraded as physical album sales declined sharply with the rise of digitalization. Even though investors recovered their original investment, the situation demonstrated that technological change could undermine expectations of stable, long-term revenues. More recently, music rights funds have purchased catalogues from established artists, betting on streaming’s recurring revenue model. Some acquisitions have performed well as streaming and royalty growth stabilised, while others have faced valuation pressure as discount rates rose and growth slowed. These examples further show the importance of the sustainability of the underlying cash flow base.

When viewed together, the case studies show that the methodology itself is not inherently flawed. Whole-business securitisations, IP license-backs, and secured royalty loans each have contexts in which they can be highly effective. The dividing line is not financial engineering sophistication, but the long-term durability and adaptability of the cash flows being pledged. When stability assumptions hold, RBF structures can perform almost invisibly. When they fail, the rigidity designed to protect investors can limit a borrower’s ability to adjust, restructure, or reinvent itself.

Conclusion

“There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” – Milton Friedman (1975)

Finance and economic theory revolve around trade-offs. How can I give up the least and gain the most? For many founders, RBF is the answer to this question (when discussing financing), but for others, a costly mistake. RBF may eliminate the disadvantages of both or simply combine them. What may seem like free money in the short term can turn out to constrain flexibility and limit upside in the long term. The ultimate judgement on the effectiveness of RBF is personal. Each firm that possesses specific characteristics enabling RBF has to judge for itself whether this trade-off is worth it.

0 Comments