Introduction – NPL definition

The term NPL stands for “nonperforming loans” and it is about loans whose collection by banks has become uncertain, not only for the total repayment but also for the interest portion. Non-performing loans are generally the result of an adverse economic situation, but often also of an inefficient credit assessment by banks. Indeed, this is something that many Italian Banks might be guilty of.

It is important, however, to note that the commonly used term non-performing loans (“NPL”) is based on different definitions across Europe. To overcome problems, EBA has issued a common definition of Non-Performing Exposures (“NPE”) which is used for supervisory reporting purposes.

In Italy, banks are also required to distinguish among different classes of NPE:

– Past Due: Exposure to any borrower whose loans are not included in other categories and who, at the date of the balance sheet closure, have Past Due amounts or unauthorised overdrawn positions of more than 90 days.

– Unlikely to Pay: exposure to loans in which there is a significant likelihood of the debtor not fulfilling his credit obligations. This category substitutes the old sub-standard loans (“Incagli”) and restructured loans (“Crediti Ristrutturati”)

– Bad Loans: In the third category of non-performing loans, the most grievous for the banking institutions, we find all the claims that the bank has towards debtors who find themselves in a state of insolvency or substantially equivalent situations, regardless of any loss forecasts made by the bank. This non-solvency status need not be judicially established.

According to the definitions of non-performing provided by EBA, an exposure ceased being non-performing when:

1. It has met the exit criteria out of impaired and defaulted categories;

2. An improvement in the situation of the debtor makes the full repayment likely according to the original or modified (forborne) conditions;

3. The debtor does not have any amount past-due by more than 90 days.

Particular attention is also given to forbearance measures: concessions towards a debtor facing financial difficulties. They consist of modification of the terms and conditions of the contract or total/partial refinancing of the exposure subject to financial distress situation of the debtor Forborne exposures are transversal to the non-performing and performing one and therefore the regulator pays a particular attention to them, given also the concrete risk banks could exploit a lack of regulation for using forbearance measures and modifying loans’ status. In general, the application of a forbearance measure is accompanied by an assessment of the financial situation of the debtor with the help of specific triggers like the increase of probability of default (PD) of the borrower. This is useful first of all to evaluate whether the borrower is facing financial difficulties, but also to be sure that the application of the new measures on the loan, does not lead to a modification of the status of the debt.

Italian Macroeconomic Conditions – Past, Present and Future

Being one of the main countries impacted by the sharp rise in the stock of NPEs in the last decade, Italy has seen a slow resurgence from this fundamental problem. The analysis of the reasons for the slow deleveraging strategy of Italian banks can be complex as many variables and factors must be considered.

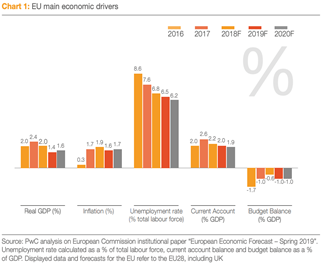

In general terms, the macroeconomic conditions of the global economy and the country in which banks operate can be considered a good starting point. Based on recent coverage of some of the most important macroeconomic indexes, all of the research existing out today conveys a picture of a country with an anaemic economy which consistently lags behind the EU averages.

Source: PwC

In particular, real GDP rates of growth in Italy have consistently underperformed the European ones and are expected to do the same soon. This inevitably adds pressure to the overall stock of NPEs. It is reasonable to assume that when the economy grows at a healthy rate, NPEs stocks would drop as borrowers could easily pay their periodic obligations and there would be very few reasons to refinance or restructure a debt contract. This aspect is further stressed by the high rates of unemployment that Italy recorded, averaging at 11.06%, against a European average of 7.14% which is consistently trending down towards the ECB targets.

Despite the relatively negative picture depicted in comparison to the European Union, Italy has still benefitted from overall improving labour market conditions and rising consumer confidence, boosting overall demand. Confidence has also grown in terms of investments from firms which are also encouraged by recent economic policies from the Italian government.

The debt-to-GDP ratio in the last 4 years has remained relatively constant thanks to a modest pickup in GDP growth and primary surpluses as Current Accounts show in the Italy graph. Indeed, Italy has shown important trading surpluses thanks to its exports.

Still, public debt remains at high levels and has become one of the main drivers of spreads between German Bund Yields and BTP Yields, showing the confidence of investors towards the general Italian economic condition.

The Italian NPE market

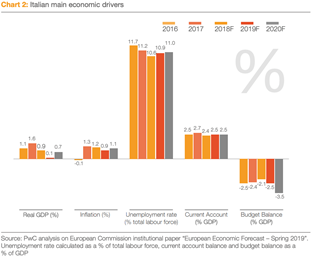

The overall stock of NPEs accumulated by banks in the Italian system reached a peak of EUR 341bn in 2015, growing at a CAGR of 22% since 2008. Going into more details about the composition of these NPEs, €200bn were Gross Bad Loans accumulated, 58%, hence more than half of the maximum amount reached in 2015; €117bn were in Gross UTPs, the stage at which loaned amounts can still be recovered through an active involvement of the bank in the recovery process; €7bn were in Gross Past Due. It is also interesting to stress the fact that in 2015, Corporate Gross Bad Loans reached a staggering 81% of the total, against 19% of Households Gross Bad Loans. As the majority of these Corporate Loans were intended for SMEs (Small-Medium Enterprises), their higher sensitivity to economic cycles and the negative economic landscape that Italy experienced, had a logical domino effect on the impossibility of these enterprises to pay their obligations when due.

Source: PwC

One of the consequences of the surge in percentages of NPEs is the fact that banks must increase their Provisions on Loan Losses, which, divided by the total amount of Gross Loans, gives the so-called coverage ratios. In simple terms, banks will try to predict a possible percentage of future losses on their loan portfolio to smooth sudden losses on their profitability and financial results. As a result, provisions which are set aside are accumulated on the balance sheet and recorded every year on the income statement as a cost that negatively impacts the bottom line. So, higher coverage ratios, implying higher provisions for loan losses will have a negative impact on net income which also has depleting power on bank capital, so banks will be required to introduce more capital, lowering ROE and forcing them to use financial sources as cushion instruments, instead of investing them in more loans or attractive instruments. As of 2019, coverage ratios have reached a level of 65.4% from a low of 34% in 2009.

Still, the last years so a better environment for banks as total stocks of NPEs have significantly decreased at a CAGR of -19% since 2015, reaching a low of EUR 180bn in 2018. In particular, the downward trend has mostly involved a deleveraging process of Gross Bad Loans and UTPs, even though Unlikely-to-Pay Loans have been decreasing at a slower rate, relative to Gross Bad Loans. The reason for this improvement has to be found in a constantly evolving Servicing market which is becoming more and more efficient. Starting from UTP transactions, these have increased but are mainly concentrated in bailout processes. This means that there is still the need to improve a specialized market for UTPs if compared to the more efficient Bad Loans Market. For instance, frequency and volumes of UTP transactions are still lagging behind Bad Loans.

As ratios of Gross Bad Loans are decreasing thanks to recent high volumes of transactions, the weight of UTPs on the overall asset quality of banks has been increasing. Main UTP transactions have involved top-tier banks and focused on the creation of large and complex deals involving pure UTP portfolios.

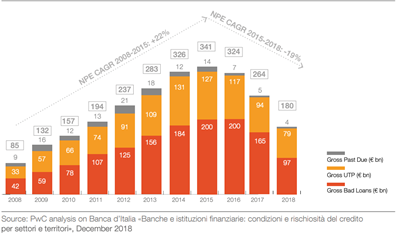

Source: PwC

On the other hand, a servicing market for Bad Loans is continuously evolving, making it easier and easier to deleverage this portion of NPEs with more transparency, lower discounts and transaction costs. As of 2018, a peak of €84.2bn worth of Gross Bad Loans has been sold to investors, mainly in the form of packages of both secured and unsecured loans, which ultimately diversifies the risk of unsecured ones and makes them more marketable.

The Italian real estate market: a driver for recovery

The 2008 financial crisis and the insolvency of millions of households have left banks with balance sheets loaded with real estate, demonstrating financial institutions’ historical preference for real estate backed loans, mainly due to a more moderate responsiveness of real estate prices to economic cycles and to lower turnover with respect to other financial assets. As a result, a majority of NPLs are backed by real estate, which is a core driver of the NPLs’ value.

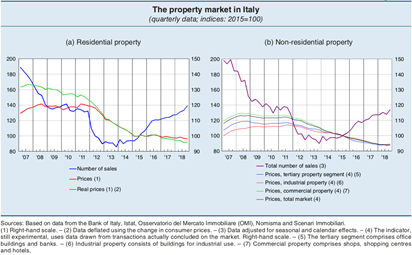

After three years of growth and a particularly strong performance in 2017, the volume of investment in the Italian real estate market slowed significantly in 2018, dropping 22% YoY to €8.9bn and marking a backdrop also relative to the EU, mainly attributable to a combination of political uncertainty and the resulting increase in the spread, a slowdown in credit availability, and a moderate contraction in international investments. While the real estate cycle is still in an expansionary phase in most European countries, in Italy the industry is having difficulties gaining traction: despite an increase in the number of sales, prices for both the residential and non-residential property sectors have continued to decrease.

Source: Bank of Italy

After the crisis that has affected the sector for the last decade, the Italian residential sector is starting to show some signs of recovery. The 2018 number of residential transactions was in line with the Italian long-term average calculated since 1958, while the number of mortgage applications for the purchase of a home rose 2.1% in the same year. North and Central Italy are the preferred areas for investors: Rome has reaffirmed its relevance as a resilient market with a deals flow that has always overbeat the national average and a 3.2% growth in the volume of investments in 2018, while Milan has shown signs of a faster recovery since 2013 and a 5.4% YoY growth in 2018. Regarding the financing scenario, Italy has historically been a market with a significant number of houses purchased without a loan: in 2018 outstanding mortgages were equivalent to 22% of GDP, with respect to an EU average of about 47% of GDP, therefore representing a relatively small market. Over the last two years, interest rates on fixed-rate mortgages have moved in the 2.0-2.2% range, while the ones on variable rate mortgages have been between 1.5 and 1.6%.

The office sector in the cities of Milan and Rome in 2018 was equally promising: both cities reached record-setting levels of take-up and a great dynamism generated by the removal of some large companies, which moved their offices or merged several offices into a single headquarters.

Lastly, the hotels sector posted a strong performance with a transaction volume worth approximately €1.3bn and 60 deals closed throughout 2018, implying that 2017 and 2018 have been the two best years in terms of volume invested in the sector over the last two decades. Around 80% of the invested volume was concentrated in the luxury markets of Milan, Rome, Venice and Florence, with 57% of investments coming from abroad.

Securitization process and GACS

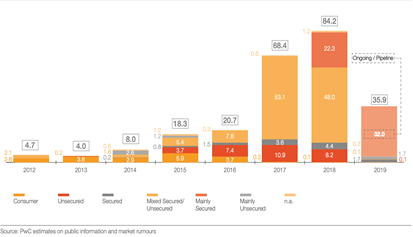

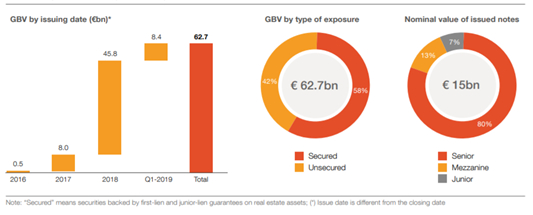

In an attempt to help the banks offload €200bn of NPLs from their balance sheets, the Italian government introduced the GACS scheme in 2016. GACS, in essence, allowed banks to securitize their portfolios of NPLs and purchase a guarantee from the government for the most senior tranches of debt. The structure of such a transaction is shown below.

A private securitization vehicle (an “SPV”) buys NPLs from the relevant bank. The SPV issues asset-backed securities (“ABS”) to investors and uses the relevant proceeds to fund the purchase price of the NPLs. The Italian government will guarantee the most senior tranche of debt in these SPVs, and the banks will buy this guarantee from the government. The price of the guarantee reflects the cost of insuring debt issued by a basket of Italian corporates and financials against default, as measured by credit default swaps (CDS). This guarantee dramatically reduces risk for investors (as state guarantees make the senior notes equivalent to government bonds in terms of risk), while also reducing the financing cost of the SPV. Since its inception, the prices for NPL portfolios sold through GACS have been up to 30% higher than the prices for those sold without GACS.

Source: PwC

As shown by the graph above, since the introduction of the scheme in 2016 to Q1 of 2019, €62.7bn of NPLs (gross book value) have been securitized and sold to investors. The traction of the scheme among both the banks and investors was initially low, with only €8.5bn issued in the first two years. Nonetheless, as banks became more strategic in securitizing and marketing their NPL portfolios to customers, volumes eventually picked up and reached €45.8bn in 2018. One criticism of the scheme is that it does not address the disposal of UTPs. This is a very important point because out of the total gross value of €180bn in NPEs, banks have a net value of €84bn on their books and out of that €84bn, only €33bn qualify as NPLs while the other €51bn are UTPs.

Impact of IFRS 9

In addition, the introduction of IFRS 9 accounting standards in January 2018 changed how banks recognized losses on and made provisions for their NPLs. One of the key differences was the movement from an Incurred Credit Loss model used in IAS39, the previous standards, to an Expected Credit Loss model (ECL). Previously, with the incurred cost model, a credit loss was not recognized until a credit event occurred (the loan becoming past due for more than 90 days). Only then was the impairment reflected on the financial statements and the adequate provision was made on the balance sheet.

Under IFRS 9, with the ECL model, you take a more forward-looking approach. At origination, banks are required to analyze historical, current and forward-looking information (including macro-economic data) related to the client. They then assign each loan issued to one of the three stages shown above based on the creditworthiness of the client. At Stage 1, loans are considered performing but banks are still required to recognize credit losses of and make provisions for 12 months. Each subsequent stage requires banks to recognize larger losses and make additional provisions. Banks are then required constantly monitor borrowers and should a borrower become less creditworthy (i.e. weaker earnings, macroeconomic shocks) throughout the lifetime of a loan, banks could potentially have to move the loan up to stage 2/3 and recognize additional credit loss. It does not matter whether the borrower is consistently paying interest and principal payments. As soon as the borrower becomes less creditworthy, a credit loss is recognized. An additional difference in IFRS 9 is that when valuing their portfolio on NPEs, banks have to include disposal scenarios in their valuation. These are scenarios where a bank would have to sell off their NPEs in an extremely short time. Such “fire sale” scenarios yield much lower valuations and have decreased the overall valuation of NPL portfolios, leading to greater impairment charges.

These changes have led to considerable changes in the balance sheet and operations of banks. Firstly, there has been a reclassification of many loans: many loans previously considered performing have now been downgraded to either UTP or NPLs, leading to higher impairments charges and provisions. The valuation of loans has been further depressed with the use of disposal scenario valuation methods. The use of the expected loss model and disposal scenario valuation has also increased NPL coverage ratios, shown in the graph above, as banks are forced to create provisions along with the additional impairment costs. It should also be noted that determining the credit risk of borrowers from origination to maturity requires significant due-diligence and monitoring, increasing the costs for banks.

NPL portfolio Valuation drivers

There is no unique methodology to nail the valuation of a distressed mortgage note, but all of them narrow down to the assessment of the collateral value. Different acquisition prices can derive from the different parameters taken into account when presented with an investment opportunity.

The first difference is made on the GP’s mandate spectrum. Real Estate investors can still pursue Core/Value-Added/Opportunistic strategies through acquiring NPEs. At first, they acquire a batch of RE collateralized loans at a substantial discount compared to the collateral value. This happens because they must undergo a several years period during which the creditor engages with the court. If the loan is worked out properly during the credit stage, the fund can end up being the direct owner of the collateral. By targeting different strategies and returns, funds can transform the asset in what they think is its best use and then sell/lend it to the market, depending on their investment objective.

The second difference is based on the NPE stage of non-performance. UTPs embed a higher chance to see it reverting to performing and UTP borrowers have a higher probability to refinance their debt. Both implications raise the loan value, regardless of the collateral value. Recent vintage implies that the borrower recently entered a liquidity crisis as well as the information provided by the bank is updated and more reliable. Moreover, having no court’s asset lockups make it easier for the asset manager to recover the value bypassing litigation. NPLs are usually priced at a higher discount, with a valuation strictly based on the asset disposability options, in terms of restructuring/building up opportunities and on the investment timeframe.

The third difference is made on the waterfall of recovery cash flows. It depends on the lender’s lien. First lien mortgage owner is the first creditor receiving money from the asset sold out (after paying court expenses), up to when the debt is paid in full. Then and only then, the second lien mortgage owner sees its debt repaid with the rest of the sold-out amount. The game keeps until the money on the table available for payback is exhausted.

Last but not least, the fourth difference is made on the loan collateral intrinsic value opportunity. The investment professional, together with technical managers, build up an investment plan where it details the CAPEX, OPEX, exit revenues and leverage strategy. Every cash flow is then discounted at the fund’s target IRR to come up with an acquisition price. The business plan is a fundamental piece of information which takes into account all the first three points, together with the market’s expectations and asset’s future usage.

0 Comments