Introduction

This article focuses on one of the oldest and most complex trading assets available – Commodities. From its natural explorations to its transformations and massive chains of transportation and storage transactions, Commodities are at the core of economies around the world and a major driver of globalization. Below, we discuss the story of the modern commodities trading industry as well as explore ways of calculating its fair value and how to hedge associated risk.

Commodities: what are they?

Commodities trading makes up a large part of financial markets, and many active firms have a crucial role in managing the distribution of goods we consume every day. Think about corn, soy, and liquified natural gas or only oil: a massive network of corporations is responsible for production, warehousing, delivery, refining, and selling these goods. Likewise, trading houses help the commodities move smoothly across the entire cycle, managing transformation across space (transportation), time (storing) and form (altering the composition of the commodity to change quality or grade).

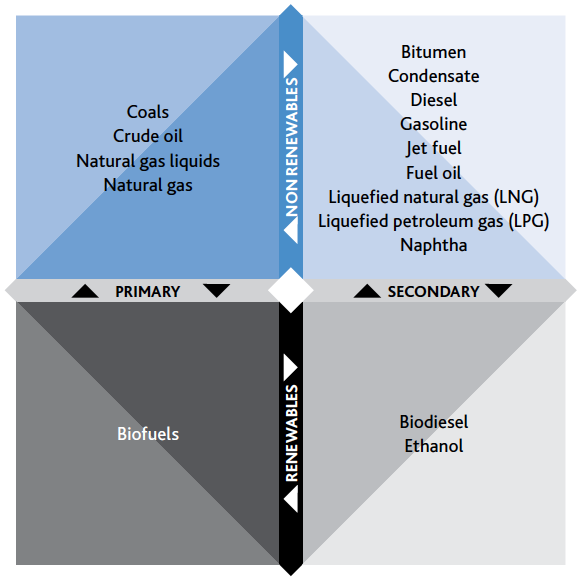

We refer to commodity as a good that has a physical nature and is the natural forces’ product. Sometimes, the public thinks it is something freely interchangeable or reachable. But that’s not always the case. Indeed, every commodity shipment is almost unique, as it depends on its exact source (in space and in time). Moreover, we can even split between primary and secondary commodities. The former are unrefined products extracted from wells, mines, and farms. The latter comes from refined primary commodities. Think about bitumen, gasoline: they all come from oil, which is a primary commodity.

Usually, we can cluster commodities into four groups:

- agricultural: grains and oilseeds (corn, soybean, oats, rice, wheat), livestock (cattle, pigs, poultry), dairy (milk, butter, whey), lumber, textiles (cotton, wool), and softs (cocoa, coffee, sugar);

- energy: crude, natural gas, natural gas liquids, coal, and renewables, refined and processed into many different petroleum products and fuels, from bitumen to gasoline, biodiesel, and LNG (liquefied natural gas);

- metals and minerals: among which copper, nickel, zinc, lead, and iron ore.

Commodities for heat, transport, chemical manufacturing and electricity.

Source: “Commodities Demystified”, Trafigura, II edition

A brief overview on the role of commodity trading firms

Different firms specialize in trading a selection of these products. Glencore, Vitol, Trafigura, Mercuria, and Gunvor are active in the energy, metals, and minerals market, while Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland, and a few others in the agricultural products. Typically, they operate over-the-counter, i.e., they match buyer and seller looking for a particular product. That is opposed to trading through a centralized electronic exchange as it happens for, say, stocks. That’s because of what we said earlier: physical commodities typically vary by grade, quality, and location. Indeed, there exist standardized futures contracts for oil, and we’re usually informed of their prices when looking at WTI or Brent quotes. Nevertheless, future contracts are not used to move around oil but as a benchmark for pricing other contracts or hedge risk. Indeed, when a player enters into a future on oil, he will almost surely settle the contract a few days before expiration (not getting physical delivery).

It’s important to understand that these firms add value to the commodity market through transformation, that can be:

- in space: simply shipping commodities around the world;

- in time: storing goods and drawing down inventories, trading firms can deal with temporal mismatches in supply and demand and smooth fluctuations in the price of the underlying;

- in form: mixing and blending raw products to suit best the client’s needs.

These channels can give rise to arbitrage opportunities, which are more frequent here than in other financial markets. For example, if a transaction initially involves selling commodity X from A to B, a trading house could optimize the same transaction by finding new intermediate counterparts. The same good X can be provided to B by a much nearer source, hence reducing shipping costs. At the same time, A can sell its product to a nearer client, again decreasing shipping costs. The original contract will be executed, but as a combination of different transactions.

For a commodity firm, it is imperative to minimize the overall cost of acquiring commodities from suppliers. For this reason, players have traditionally controlled a sizeable portion of commodity supply chains, developing proprietary transport infrastructure and logistics, hence limiting the competition from smaller players. At the same time, they have secured supply sources upstreaming or signing long-term offtake pre-payed agreements. For example, Glencore began operating as a trading house but then became a mining company integrating its business vertically. Similarly, Mercuria, Vitol, and Trafigura own mines and wells.

Simultaneously, the firms need to take care of the logistics, a mix of road, rail, overseas, and pipeline transportation. For this reason, trading firms usually have an internal shipping and chartering desk responsible for arranging cargo rent. Notice that different commodities require a specific freight system. For example, LNG cargos have a built-in system to refrigerate the gas at -162°C to reduce its volume, while bitumen tanks maintain the product heated to 150°C so that it does not solidify.

Control of midstream infrastructure is also a crucial part of the business. As we said before, trading firms store resources to react to demand and supply variations in loading and offloading terminals and storage and blending facilities. In this way, operators can offset market shocks’ effects (think about political unrest, unseasonal temperatures) by adjusting inventory levels. Ownership of these facilities is crucial for profiting from arbitrage opportunities, as these require enough flexibility in that allocation of resources. Besides, storing infrastructure helps small, independent producers to have an export outlet. For example, Trafigura’s Impala Terminals at Porto Sudeste (Brazil) helps smaller iron ore miners to find a market for their product.

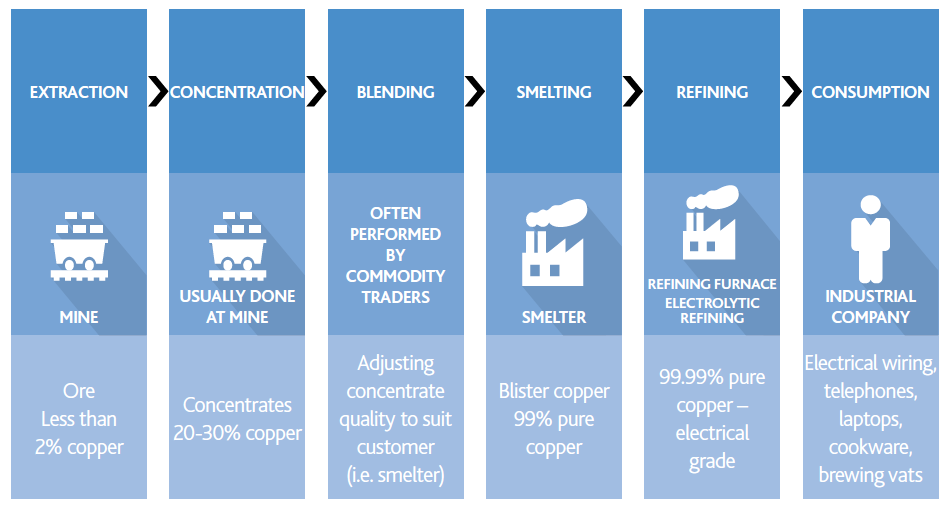

Simultaneously, storage facilities help blend commodities coming from different sources to best suit the customers’ needs. That is indeed important in the copper market. The surge in copper demand led by China since 2000 led to the depletion of existing mines requested producers to look for new ones. Often, the new sites proved to be rich in arsenic. For example, the Toromocho mine in Peru and Codelco’s Ministro Hales project in northern Chile produce copper with an arsenic content equal to 1% and 4% respectively. Such values pose health and safety risks to smelters and users; therefore, China imposed a maximum 0.5% arsenic content on imports. Trading houses deal with this problem by blending low quality with high-quality materials.

Copper life cycle

Source: “Commodities Demystified”, Trafigura, II edition

Planning all these steps efficiently is crucial for the profitability of a commodity trading firm. As the end customers are usually strategic organizations like government agencies, energy-intensive manufacturers, and utilities, disruptions in the supply chains can have unpleasant consequences.

Commodities’ role in a trading portfolio – diversification is KING

Although the first futures contracts have been created and described in the Hammurabi’s Code in Ancient Mesopotamia, allowing exchanges of goods at a future date at a specified price, it was the demand for standardized agricultural contracts in the 1800s which has led to the development of modern commodities futures exchanges.

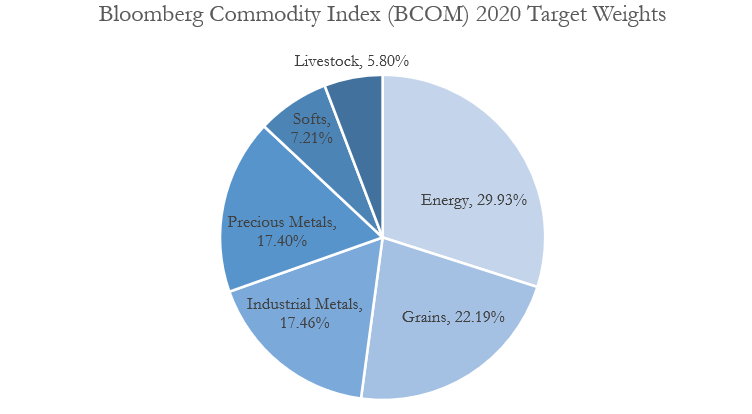

Apart from the entities involved in commodities’ numerous interconnected supply chains, also financial investors add commodities to their portfolios, seeking diversification in seemingly uncorrelated assets. Following the inception of commodity futures indices in the 1990s, they have become a separate asset class with well-established benchmarks and a wide array of ways to gain exposure to the commodity markets.

There are mainly three key benefits resulting from commodities allocation:

- Inflation protection

- Diversification

- Return potential

Since commodities are physical, real assets, they are driven by more typical market forces, greatly affected by the economic fundamentals, driving both supply and demand. In general, commodity indices tend to be uncorrelated with traditional financial assets, and well correlated with inflation indices. Looking more closely, the best performers as a hedge against inflation have been precious metals, such as gold or silver, and energy, but for e.g. industrial metals or agriculture, the effect may even be negative. On top of that, precious metals can be also seen as a safe haven asset and a hedge against geopolitical risk, which gained in attractiveness due to a low alternative cost of allocation in the period of low rates.

Following the 2008-2009 recovery, commodities have been showing a strong positive relation to the equity indices, mainly driven by the fall, and then recovery in the aggregate demand, but afterward the commodity indices have returned to be driven by other supply factors. However, commodities also show larger price fluctuations than traditional financial assets due to risks of natural disasters, geopolitical risks, liquidity risks, and other environmental and infrastructural risks. This higher price volatility could have been observed for example during the turmoil in oil prices following the COVID-19 shock earlier this year. Hence, overall due to these factors’ commodities may be better suited for active traders.

Gaining Exposure

Typically, investors have four distinct ways to gain exposure to commodities:

- Direct physical investment

- Commodity futures

- ETFs

- Commodity-related equities

Naturally, investing in a physical commodity, e.g. a barrel of oil, provides the purest form of exposure and natural intrinsic value, however, it is also highly impractical, and accepting the delivery of a standardized contract is associated with high transportation and storage risks. Therefore, commodity futures contracts seem like the most natural option, allowing for highly liquid trading and provide a good price discovery mechanism for commodity markets.

Another possibility is investing in the commodity index ETFs which should allow for a comparable exposure, however not all ETFs are equal. Some hold physical assets, while others invest in commodities via futures contracts, which bears a risk of selling low and buying high when the contracts are rolled over. The correlation with commodity prices obtained by investing in commodity-related equities varies depending on the sector and the firm. On one hand, the leverage may be higher, but at the same time, these firms may experience other risks stemming from their financial structure or performance of other business units, as well as e.g. securing a price on a forward basis and thus not fully benefiting from a market move.

Determining Theoretical Fair Prices

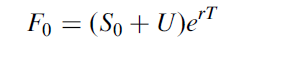

Commodities differ from financial assets or currencies, as they do have storage costs. Since storage costs can be treated as negative income, then considering U to be the present value of storage costs, by the no-arbitrage condition we obtain a formula for a fair price of a forward contract given by:

Had the price been lower, the arbitrageur could buy a futures contract for one unit and sell the commodity, saving on storage cost, and investing the amount at the risk-free rate. This may be true for investment commodities, such as gold or silver, however for individuals and companies willing to use the commodity for consumption it is not a viable solution. Another factor is the lack of ability of many investors to short the asset. Therefore, for consumption assets, we can conclude with the following general equation:

For some commodities, there may be a perceived added benefit to holding the physical asset as opposed to the futures contract, allowing e.g. to maintain a certain output in the times of supply shortages. This is referred to as the convenience yield, which reflects the market expectations of the availability of the commodity at future dates. The higher possibility of a supply shortage, or the lower the inventories, the higher the convenience yield. The relationship between futures and spot prices can be then described in the form of cost of carry, which accounts for storage costs (u) plus interest paid to finance the asset (r), less the income earned on it (q). Denoting the cost of carry as c = r – q + u, and applying the correction for convenience yield, denoted by y, we obtain:

Source: IG Markets

The situation when the futures price is below the expected spot price is known as normal backwardation. In this case, the convenience yield is higher than the cost of carry, and the basis is positive. In the opposite case, when the futures price is above the expected spot price it is said that the market is in contango or in a “negative basis”. Normal backwardation can result from higher current demand for an asset than at the time of expiry of the relevant futures contract. Contango occurs when there is an expectation of an increase in the price of an asset over time. In both cases, it is usually expected that the prices will converge toward the spot prices as the contract approaches maturity. Managing this basis risk is one of the key elements in trading commodities.

Managing Commodity risk Exposure:

One of the fundamental activities of commodity trading firms is to hedge exposure to price fluctuations of their portfolio of primary and secondary products. As mentioned above, diversification is a major source of protection, however there are also other methods used of which two of the main ones are briefly described below:

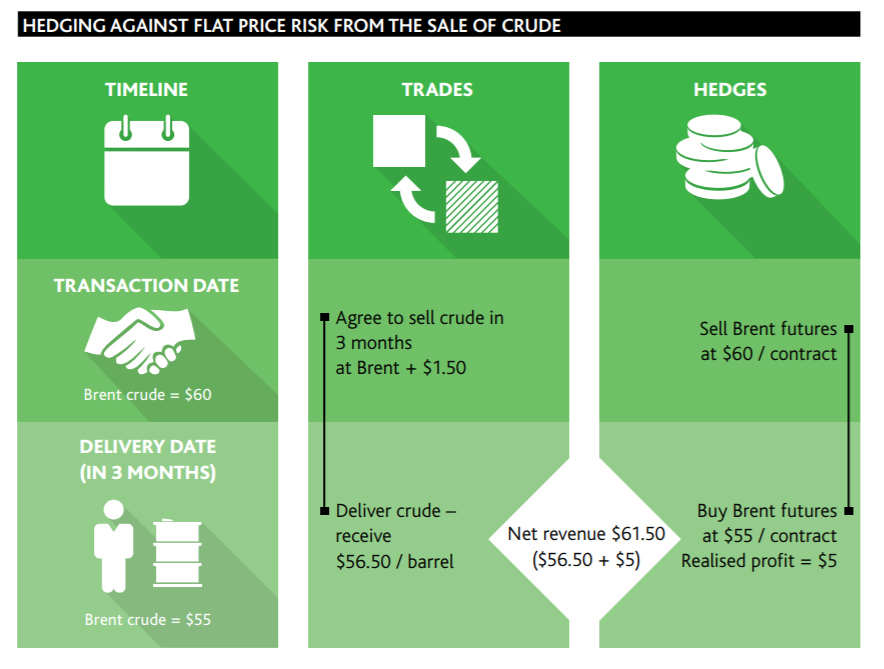

1.Managing flat price risk – the risk of a change in the benchmark price for a barrel of oil or a tonne of copper concentrate for example. In a typical transaction, a trader will agree purchase and sale prices with two different counterparties to lock in a profit margin. The transaction is agreed before shipment and the convention is that final prices are not fixed until the commodity is delivered. Hence, on the transaction date, the parties agree both trades at fixed margins against a benchmark index price. This leaves the trading firm exposed to changes in the actual price of the commodity which can be hedged by simultaneously taking out futures contracts against both parts of the transaction as evidenced below:

Hedging Flat Price Risk

Source: “Commodities Demystified”, Trafigura, II edition

2. Basis risk: managing flat price risk does not eliminate price risk altogether because many times physical commodities’ prices are not perfectly aligned with futures’ prices. This is the core characteristic of traders’ skills, as understanding basis risk is the source of profitable trading opportunities. Here the objective is to “play” the standardization of futures contracts versus the physical quality of commodities.

Finally, there are also other sources of risk which must be considered such as operational risks of working in multiple jurisdictions, or hedging freights, to country credit and political risk or reputational risk. Commodities trading is massively complex, however very exciting and profitable if well done.

0 Comments