Introduction

Following poor harvests in Africa due to bad weather throughout the year, hedge funds have been pouring money into the long trade since last year betting on a continued shortage of supply. Across the two cocoa futures contracts, London and New York, speculators have a total of USD 8.7bn in bets according to the CFTC and thereby have the largest exposure ever to the cocoa market. The massive bets, albeit not being the cause of the explosion in cocoa prices, have exacerbated the effects on the prices in the futures markets.

The Cocoa Market

Cacao is a commodity crop originating from South America, specifically the Upper Amazon region and has had an important role in the history of the Americas. Cocoa was introduced through Spanish conquistadors to the European continent with Columbus bringing it back to Spain but not popularised until it hit the Spanish courts. Historically mostly consumed as a drink in the Maya and Aztec cultures, it was the same in Europe until the 18th century when chocolate in its form as a solid started to gain traction. Following the invention of the melanger -stone wheels grinding the beans in an idea not too dissimilar from a metate- by Phillipe Sucharde, and the conching machine there was not much to hold the popularisation of chocolate back.

Currently, the cacao market is one dictated by a very fragmented production and much more concentrated processing market which had a market size of USD 15.3 bn in 2022. As a whole, just the cacao market had a size of USD 21.1bn in 2022 and is expected to reach USD 26.3bn by 2027, whilst the chocolate market had a revenue of around USD128 bn and is expected to reach around USD 161bn in 2027. The largest corporations active in this market are Mars Wrigley Confectionery with net sales of USD20 bn, Ferrero Group with 15.3 bn, Mondelez with ~ USD 12bn, and Hershey company with USD 10.4bn in 2022. Others include Nestle, Meiji, Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli AG, Perfetti Van Melle, and Haribo. The global cocoa demand is expected to grow at 4.7% CAGR until 2033. Besides the food & beverage and confectionery sectors, cacao is also used in the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries albeit at a much smaller scale. The main driver over the coming years is expected to be increased usage in confectionery and food & beverage with surging demand for chocolates and chocolate syrups.

The United States currently has the largest market share in the global market with 24.6% and is expected to grow at a rate of 3.7%. Consumption in the US is shifting more towards clean-label and on-the-go products and will help spur growth in the following years. Throughout the increase in product prices over the last years, the demand has proven to be relatively inelastic, and consumption continued increasing. Cacao sales will also be boosted through the applications in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics.

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, the cacao market is expected to grow at a 2.7% CAGR with demand arising from convenience foods and a general expansion of the food & beverage industry including frozen desserts, ice cream, confectionaries, etc. India could be one of the largest drivers of overall growth with increasing penetration of the chocolate market due to changing tastes and preferences that see sweets & confectionery gain ever-increasing momentum. Alongside the shift in consumer preferences, the growing population and varieties of speciality chocolates such as vegan, and sugar-free are poised to help increase cacao sales.

Production

The centers of origin, domestication, and usage of cocoa have been the objects of hot debate. The more accredited hypothesis suggests that the cacao tree should have originated in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Upper Amazon, or the Amazonian region shared by Peru, Colombia, and Brazil. As for domestication, historians used to believe cacao seeds were first planted by Mayans ca. 1500 B.P., but recent bioarchaeological studies point to an even earlier usage, by Olmec tribes around 3500 B.P., who had probably discovered the edibility of the cocoa fruit by observing rats eating it with voracity. What is certain is that cocoa was extremely important in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and South America, where fruits were not only consumed and squeezed for juice but also used as a monetary unit and in religious rituals as a symbol of abundance. Once Europeans started exporting and planting cocoa seeds in the African continent, which, since the beginning of the 20th century, has become the biggest center of cocoa production.

Fast forward to today, West Africa is by far the world’s leading cocoa-producing region. Of the 5.8 million tonnes of cocoa produced globally, 3.9 million, nearly 75% of the total, come from four countries in West Africa. In 2022, Ivory Coast produced 2.2 million tonnes of cocoa, Ghana 1.1 million, while Nigeria and Cameroon produced about 300k tonnes each. The third largest producer after Ivory Coast and Ghana is Indonesia, with 667k tonnes per year, while South American and Caribbean countries are cumulatively responsible for about 15% of the global production.

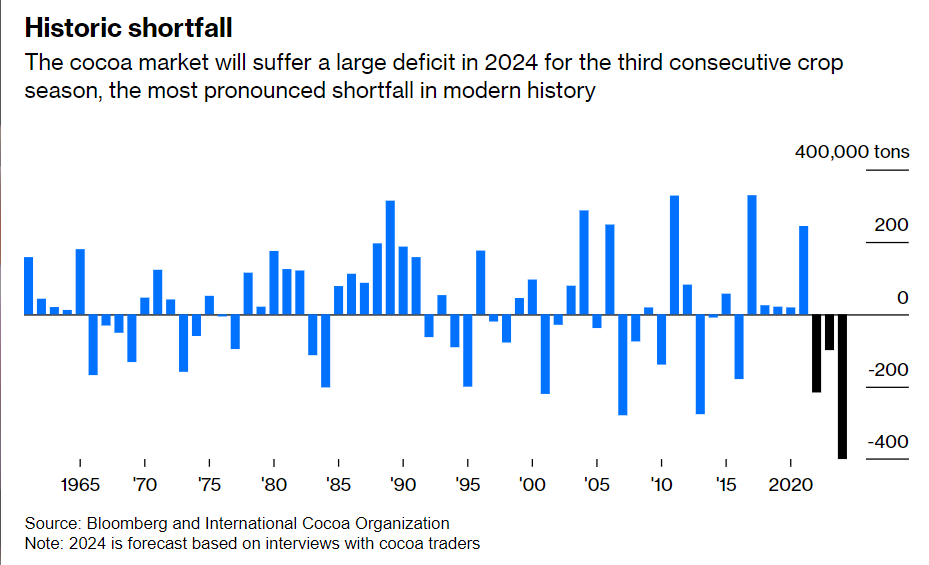

What is peculiar about cocoa production is that due to the low prices of the last 40 years, cocoa has not developed into a plantation business, like most other agricultural commodities. The overwhelming majority of cocoa crops, especially in West Africa, are still grown by 6 million small farmers, who, in a constant fight against hunger and poverty and earning an average of $1.20 a day, often lack the means to plant new trees and expand their estates. On top of that, farmers benefitted very little from the recent rally in cocoa prices, and several growers, especially in Ghana, are smuggling their output in search of better prices. This is because markets in West Africa are controlled by their local governments which sell forward contracts and guarantee a price. For the 2023-2024 crop season, the price was set at $1.63 per kilogram, about 70% below the current wholesale price. To be sure, the high prices of the 1970s and the generous incentives of the first Ivorian president Félix Houphouët-Boigny (himself a cocoa farmer in his youth), had attracted millions of African farmers, transforming Ivory Coast into the world’s largest producer, but the depressed prices of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s had devastating effects on the planting activity. Nowadays, trees are rarely younger than 25, and with the almost non-existent use of fertilizers or pesticides, plants yield less and are particularly vulnerable to bad weather and diseases, factors that are simultaneously at play this year. Cocoa trees take around five years to mature enough to yield fruit in a meaningful way. In particular, the hot dry weather of this year in West Africa was caused by a mix of drought due to climate change and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, a periodic but irregular phenomenon that gives rise to a warming of the sea level surface, disrupting the normal rainfall and wind patterns. Especially in Ghana and Ivory Coast, the extreme weather prompted the spread of diseases and delayed harvest. The compounding of all these adverse conditions resulted in a wide gap between supply and demand and a record-high deficit forecasted at 400,000 tons for 2024.

Source: Bloomberg

On the other end, the players truly benefiting from the current supply shortages are the farmers outside West Africa who have the ability to sell the beans at the prevailing market prices and the financial resources to pick up production. For these farmers in South America and Indonesia, the crisis in Africa represents a blessing.

Logistics of the cocoa market

The process of getting the cocoa beans from the tree to the processing plants or consumers is slightly different from other agricultural commodities. After harvest cocoa seeds must be extracted from the cocoa pods oftentimes manually with machetes being prevalent among farmers. These beans must then be fermented for 3-7 days by being stored in boxes or piles in the sun, the heat from the sun helps ferment the beans and is essential in developing the colour and flavour of the beans. After fermentation, they are left to dry in the sun over multiple days to stop the fermentation process mostly involving manual labour including turning them over to ensure even drying. The fermentation and drying process are important in ensuring the expected taste and doing it suboptimally can massively influence the flavour. Only after completing these steps do cocoa beans typically get sold by the farmers to an aggregator who transports beans, weighs, packages, and sorts them.

These aggregators then bring them to warehouses from which they are typically exported. At this part of the process, a differentiation between small-scale and high-end chocolate companies -more often than not correlating strongly- and the large chocolate companies arises, the former have them typically shipped directly from the producer greatly improving traceability, and conditions for the farmers, whilst the latter tend not to due to their sheer scale and drive for profitability. While shipping the cocoa beans can either be stored in jute sacks, in bulk or plastic bags. After arriving at the port in the country of destination, clients would typically collect them from the port directly or a warehouse depending on scale.

Demand for Cocoa

According to Market Insights, the cocoa market size is estimated to be around $15 billion and encompasses a variety of industries, from confectionery, food and beverages to cosmetics and pharmaceutics. In recent years, there has been a sharp rise in the production and consumption of cocoa-based products, including not only chocolate but also skin-care products and anti-acne detergents. While primary consumers remain children, the chocolate consumer base is expanding among adults, thanks to both a growing variety of flavours and its properties in lowering cholesterol and promoting muscle growth. A boost in cocoa popularity, especially for dark chocolate, has been the trend towards healthier lifestyles, as consumers become aware of the health benefits of chocolates due to the presence of antioxidants such as flavonoids, that help in preventing cancer, heart disease, and stroke.

From a geographical standpoint, while developed countries still represent the lion’s share of cocoa demand, with the US accounting for a dominant 24.6% share, the increase in global demand has been fuelled in recent years by rising demand for chocolate from emerging countries, especially China and India. The pre-Covid prevailing low cocoa prices have fostered the spread of chocolate in underdeveloped countries and across the low-income classes in richer jurisdictions. As a result, in the last five years, the cocoa demand grew steadily at a 5% CAGR.

Another emerging trend is the growing demand for sustainable cocoa products, and producers are rapidly adapting, focusing on the so-called voluntary sustainability standards (VSS) compliant products. This label is associated with socio-economically equitable and environmentally sustainable practices that, after being assessed and verified by predisposed entities, allow suppliers to differentiate their products in the marketplace, targeting those consumers who, with their consumption decisions, want to address issues like income disparities, labour exploitation, and deforestation. Various national and international initiatives such as the German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa (GIDCO) and the Swiss Platform for Sustainable Cocoa (SWISSCO) are also being launched to support sustainable cocoa production.

Cocoa futures

The two main cocoa futures include the ICE futures U.S. Cocoa futures and the London Cocoa futures. Both cocoa contracts serve as the world’s benchmarks for the global cocoa market with prices for physical delivery of African, Asian and Central and South American origins to the Port of New York District, Delaware River Port District, Port of Hampton Roads, Port of Albany or Port of Baltimore. The London cocoa futures have physical delivery to Amsterdam, Antwerp, Bremen, Hamburg, Liverpool, London, and Rotterdam and are packaged in three different ways, the first being Standard Delivery Unit cocoa bagged in terms of one contract size which is 10 metric tonnes, Large Delivery Unit in ten contract sizes and Bulk Delivery Unit with loose cocoa with 1000 metric tonnes. The contract series are March, May, July, September, and December creating ten months available for trading. There is no daily price limit and all non-African origins, so Origin Group 2 have a 50 GBP discount and the minimum price fluctuation is £1 per tonne or £10 per contract.

The trading hours of the London hours are 4:30 till 11:55 in New York with pre-open at 20:00, 9:30 till 16:55 on the London exchange with pre-open at 1 am and 17:30 till 00:55 in Singapore. The first notice day is the business day immediately following the last trading day and the last trading day is eleven business days before the last business day of the delivery month. Accountability levels for London Cocoa and Euro Cocoa (in aggregate) exist with 7 500 contracts for the front delivery month and 15 000 for the deferred delivery month, delivery limits are a minimum of 100 contracts and a maximum of 7500 contracts and the maximum delivery limit exemption is at 15 000 contracts.

What we expect from the future

As previously mentioned, farmers in West Africa are currently not benefiting from the high prices, receiving only 30% of the wholesale price for cocoa beans. Hopefully, by next season, the newly negotiated price will constitute a cash infusion for the growers, fostering replantation of the older trees and increasing the use of fertilisers and pesticides to limit the impact of diseases. This necessary price-driven dynamic would lead to a partial rebalancing of the supply and demand equilibrium in the future, but, in order to create a long-term sustainable equilibrium, challenges like the systematic poverty of West African farmers must be addressed by coordinated efforts between industry actors, including governments, standard-setting bodies, development organisations and private companies. If weather catastrophes worsen, and diseases further increase, some farmers might be left with nothing albeit the skyrocketing prices due to not being able to produce sufficiently.

On the other hand, consumers will necessarily face higher prices for all the chocolate products as companies will have to pass the higher input costs to consumers as preexisting supplies can only last so long and the strategy of reducing the amount of chocolate in chocolate products can only be done so far. Depending on how responsive consumers are to higher prices of chocolate products, the cocoa wholesale prices will increase further. Overall, we expect the aggregate supply shortages to persist well into the future -at least three years- and cocoa prices to settle at a level much higher than the previous decades, but lower than the current ones.

References

[1] https://www.ice.com/products/7/Cocoa-Futures

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/c163633a-cd9e-4962-8b7f-3d6c44463405

[3] https://www.ft.com/content/a0ecd9d0-d626-4d26-b999-36268616b6d7

[4] https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/industry-reports/cocoa-and-chocolate-market-100075

[5] https://www.ft.com/content/563227fe-edfb-40bd-bea9-dc2822ba4f27

[6] https://beyondbeans.org/2023/10/05/the-logistics-of-contemporary-cocoa/

[7] https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/epdf/10.1094/PHYTO-05-20-0178-RVW

[8] The World’s Top Cocoa Producing Countries

[9] Rising Cocoa Prices Drive Mars, Hersey to Use Less Chocolate – Bloomberg

0 Comments