The rhetoric for increased infrastructure spending as a fiscal stimulus has been particularly popular this fall. Firstly, Mr. Trump in his campaign claimed that he is going “to fix inner cities and rebuild highways, bridges, tunnels, airports, schools and hospitals”. Also, Phillip Hammond, the UK chancellor, in his Autumn Statement last week announced plans to boost infrastructure in the UK. In this article, we will look closer on how these two developed countries plan to finance public infrastructure spending, what impediments they may face and how it is likely to affect private investments in infrastructure. We also look closely at the experience of Chinese policy in this sector and explore if such policy has reached its goal.

Trump’s Plan

Trump has promised to invest $1tr in infrastructure. Indeed, the sector needs for rebuild and repair are estimated at $3.6tr by 2020.

Infrastructure Gap in the US (Source: American Society of Civil Engineers)

Mr. Trump did not elaborate in detail on how he plans to fund projects, however, the general idea is to attract private investors’ money rather than to increase public debt. More specifically, he plans to introduce tax credits, which will amount to 82% of equity investments. Out of $1tr of spending, 80% is assumed to come from project finance lenders in the form of loans, and only the fifth from equity. Therefore, the total amount of tax credits is estimated at $164m.

Complementary suggestion is to allow companies, which pay taxes on repatriating overseas profits, to use the tax credit of infrastructure investment to offset its tax liability. For example, a company, which repatriates $1bn of retained earnings and is subject to pay $100m of taxes, may choose to invest $121m in infrastructure, and arising $100bn tax credit will offset tax liability.

However, there is a major pitfall in Trump’s approach. Private investors, hunting for yield, will continue to pour money into profitable projects, like electricity grids, while loss-making ones, but still essential for society, like railroads, will lack funds. Also, poor communities may be left over without financing.

Another grim point is that the US does not have a successful track record of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs). According to the Congressional Budget Office, from 1989 to 2014, the US had only 36 privately financed road projects. Out of them, 14 are complete, three have declared bankruptcy, one required public buy-out and the rest are still under construction. In terms of number of PPP deals, the outlook has improved, with five deals being closed in 2015 and nine deals being closed in the first three quarters of 2016. However, their success is still to be proved.

Hammond’s Plan

In the Autumn Statement on 23 November, Philip Hammond introduced National Productivity Investment Fund (NPIF), which will invest £23bn in essential sectors from 2017-2018 to 2021-2022. The NPIF will be targeted at four areas that are critical for productivity: transport, digital communications, R&D and housing. During five years, £4.7bn will be allocated to R&D, £8.2bn to housing, £3bn to transport, £740m to telecoms and £7bn to other long-term investments. This increases UK’s infrastructure spending as share of GDP from 0.8% now to 1.2% in 2022.Though NPIF is referred to as a fund, it will be financed through raising public debt, more specifically, by issuing additional Treasury-backed infrastructure bonds. The Autumn Statement recommits to the UK Guarantee Scheme, which, since the introduction in 2012, has delivered £1.8bn of Treasury-backed infrastructure bonds and loans. This supported around £4bn worth of infrastructure investments in nine ventures.

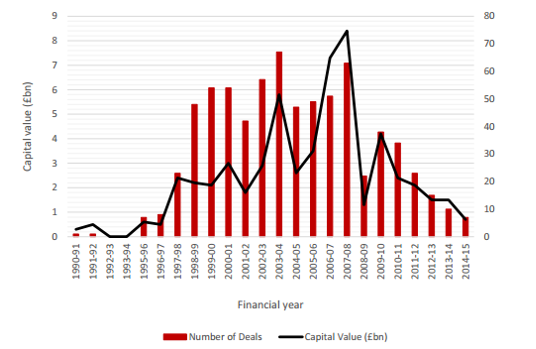

Besides bond backing, UK has an initiative which attracts private investors’ money to infrastructure projects. This is called Private Finance Initiative, which is a form of PPP in the UK, and was introduced back in 1990s. Up to date, 722 projects with the total value of £55bn have been funded with PFI. PFI largely focuses on social infrastructure – building hospitals and schools.

Number of PFI Projects and Their Capital Value (Source: Her Majesty’s Treasury)

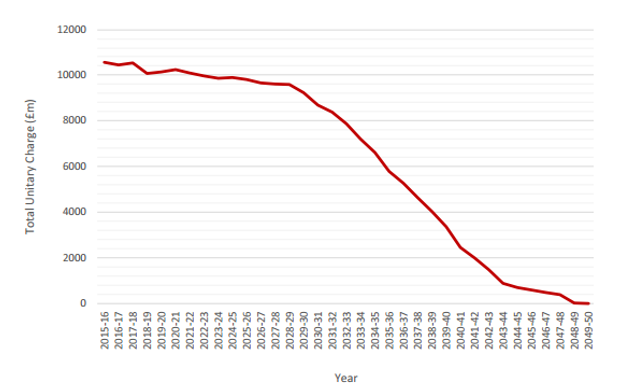

Under PFI, the public sector does not pay for capital expenses during the construction period. Once a project is operational, the public sector pays so called unitary charges, which include operations and maintenance cost and repayment of debt and interest on debt, which was issued to finance construction.

Estimated Payments Under PFI contracts (Source: Her Majesty’s Treasury)

However, there is a concern that such funding scheme leaves public sectors with immense commitments to repay, while private investors receive extraordinary returns. With around £10bn of annual repayments until 2028, initiative increases government debt by additional £220bn.

In 2012, the initiative was reviewed and rebranded to PF2. The key difference between PFI and PF2 is the timing of payments from the public sector to the private sector.

Private Infrastructure Market

According to Prequin, around $340bn are committed to private equity infrastructure funds globally. This is still less than target asset allocation. On average, institutional investors would like to allocate 5.7% of their portfolio to infrastructure, but now the allocation averages to 4.3%. Moreover, there is an excess liquidity in private infrastructure market. For instance, $75bn in dry powder is available in the US for infrastructure projects. This excess liquidity puts upward pressure on valuations and increases competition for assets. In February 2016, London City Airport deal closed at c.£2bn, which represented an EV/EBITDA multiple of over 40. British Airways even threatened to leave London City Airport if the new owner increases airport charges to get the required return on investment, and they did not see any other way of how such valuation may be justified.

Therefore, the infrastructure conundrum is that there is a huge pile of private money ready to be invested in solid infrastructure assets, but governments still spend billions on infrastructure to boost the economy. If governments could design policies that would redirect this excess liquidity into needed projects, it would both improve public finances and return outlook for investors.

Chinese Experience: It Ain’t Always Good

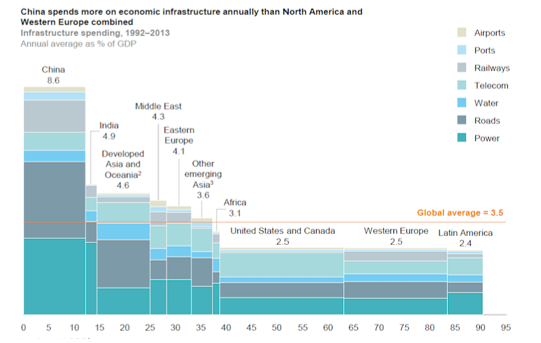

Globally the most active country in infrastructure spending on national and foreign projects is unarguably China. Relative to GDP as well as in absolute terms, the Republic spends more than any developed nation on its infrastructure.

Infrastructure Spending Worldwide as % of GDP (Source: Bloomberg)

Being an emerging country, many economists argue that high infrastructure spending is vital for enhancing continued economic growth, since capacities and connections, well-established in Western nations, have to be build up yet.

However, lately there has been disagreement on whether China might be overinvesting. Its spending on infrastructure is considered to yield lower returns than expected and increases national debt instead.

Starting with a period of economic stagnation in the 1980’s the country’s leaders have designated a focus of investments in infrastructure improvements to enhance productivity. Ever since, the Five-Year Plans for Economic and Policy development established consistent goals for growth of infrastructural elements. The latest plan from 2015 allocates expansion and spending especially with railway, street, airport and real estate construction, as well as for improvements of internet services and renewable energy supply.

Fixed-Asset Investment in Infrastructure (Source: Chinese National Bureau of Statistics)

Though most sectors are dominated by large state-owned enterprises (SOE) private and foreign engagement in infrastructure investments has increased over the course of time. Yet, international collaboration on projects in China remains highly restricted. Foreign companies are only allowed as minority stakeholders and their primary function is financing the projects, rather than implementing them. Their returns are thus relatively lower and the investment is less profitable. Most international collaborations are welcomed in projects requiring high technological expertise, which the national Chinese champions do not have.

Beginning in the second half of 2015 private investors started withdrawing their activities in infrastructural investments. This might be in part due to a drop in the currency and downgraded economic growth estimates with consequent reduced returns on investments. In order to sustain growth rate targets and economic catch-up to the West, the government allocated the shortfall of investments to be covered by its SOEs.

Before and after the shift in 2015 infrastructure investments were primarily financed and conducted by Chinese state-owned enterprises. Financing is typically acquired through debt, a safe method taking into account the low probability of default for SOE’s.

The missing danger of default and the requirement to fulfil investment volumes might induce SOE’s to forego a thorough investigation of profitability of certain investments.

Indeed, a study published in the Oxford Review has now found that not only are costs of infrastructure projects in many cases underestimated and exceed projected expenses by 30% on average (transportation sector). Furthermore, a high proportion of investments turned out performing worse than forecasted. Infrastructure, which is not used as much as predicted will not produce the monetary benefits expected from it. Thus, loans taken out for such investments turn into non-performing loans, which pose an economic burden for the company involved.

In the case of China this problem is conquered by state-owned banks taking on the non-performing loans from infrastructure investments. Increased funding provided to these banks by the central bank prevents defaults, but also entails involuntary monetary expansions.

The large scale of infrastructure investments in China through state-owned enterprises, might have sustained overall economic growth rates at a high level for the moment, but it also gave rise to future risks of revenue shortfalls and economic fragility.

As the major financing mean for infrastructure investments large proportions of debt have been built within state-owned corporations and banks. Accounting for these debts as part of overall government debt, means that the Chinese government debt as a percentage of GDP has by now risen to about 200 percent, making it the world’s second most indebted government.

Hasty choices of infrastructure projects, based on incomplete examinations of their profitability, lead to an increase in non-performing loans on the state-owned banks’ balance sheets. Consequent monetary expansions to prevent these banks from default caused economic fragility.

Summarising the consequences of China’s unprecedented level of infrastructural investments, one has to conclude that instead of laying the foundation for economic prosperity, it lead to increased economic fragility, which might cause an economic and financial crisis in the future.

Conclusion

Though increased infrastructure spending is aimed at boosting the economy, only if carefully designed it will for sure help economic growth. Infrastructure spending financed by public debt increases the burden for already indebted countries, and PPPs did not prove to be particularly successful in countries we have looked at.

[edmc id= 4442]Download as PDF[/edmc]

0 Comments