In the previous article of our series, we highlighted the questionable use of cross currency swaps and concluded that this kind of window dressing techniques are a manifestation of the larger issue of problematic debt management on the sovereign entity scale. In this article, we delve deeper into the vital need for more economic realism and respond to the growing concern of debt unsustainability. We will propose GDP-linked bonds as a tool for debt flexibility and debt related risk reduction. We will begin with presenting the history of these bonds and their contemporary economic relevance. Then we will attempt to discuss the instrument’s pricing before moving onto evaluative case studies.

GDP and bonds: a not-so-new combination

GDP-linked bonds are a redemption opportunity for countries that have lost creditworthiness, credibility, or were merely unable to keep their debt sustainable. In most cases, history quickly forgets that a haircut on the bonds deemed safe are labelling the country with a stigma for many years. Risk-averse investors don’t forget the bruise, and hence it takes many years before the Ministry can tap again into the debt capital markets. In financial jargon, some “sweeteners” are needed to restore the investor’s taste.

Indeed GDP-linked bonds are not unique in their feature, but rather belong to the bigger subset named “state-contingent bonds”, that is fixed income securities having equity-like behaviors. Most closely related to them are convertible bonds in the corporate world, wherein if a certain condition is met, the investor can benefit from a certain set of conditions. In this case, predictably the performance of GDP-linked bonds is tied to the Gross Domestic Product of a country, the latter of which can dictate both the coupon and the principal, according to a tailored design.

Despite being thinly traded, GLBs potentially offer an in-built mechanism to stabilize public debts in an environment of uncertainty. This is especially valuable where indebtedness is at sustainable, but high levels and winding down debt through conventional adjustment takes time. Investors, on their side, are interested in a reduction of the risk of outright default. Hence, we can suppose it is reasonable for them to be pleased at a greater stabilization of the debt/GDP ratio which is so often feared today.

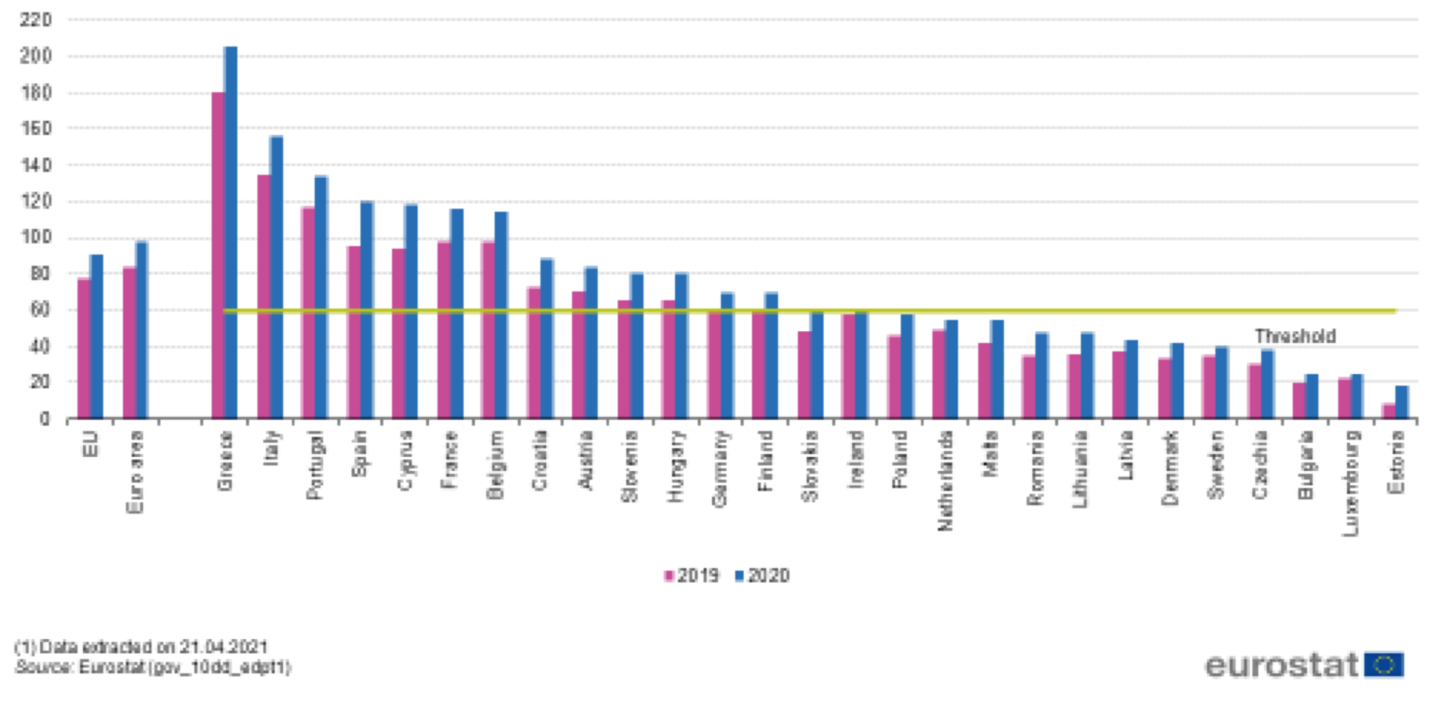

This instrument, which was widely disregarded in the past, might have potentially gained relevance in the current macroeconomic environment shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic. An environment which has loudened the need for even more excessive borrowing and has raised the question of debt sustainability throughout the economic cycle. The “Debt Sustainability Monitor” of 2020, a report by the European commission, which was released in January, estimates that government deficit ratio increased, last year, by approximately 8 percentage points to 9% of GDP. The aggregate government debt-to-GDP ratio rose by a staggering 15 percentage points in 2020, reaching respectively 95% and 102% in the EU/EA. Which is also expected to continue rising by around 1-2% in aggregate over 2021 and 2022. It is reported that the pandemic’s effect on public finances is expected to be significantly more detrimental than the 2008 crisis.

Source: Eurostat

History: Argentina and Greece

As for a great deal of financial innovation and proposals that welcomed the new century, it is unsurprising to hear that GDP-linked bonds have been first proposed by Robert Shiller in the 1990s. In “Macro markets” (Shiller, 1993), the author calls for the need of a security linked to GDP as a step towards completeness in financial markets, letting sovereigns share their risk associated with growth uncertainty and allowing financial agents to both invest and hedge their economic exposure to a whole country.

As it has been mentioned, as of now the issuance of GDP-linked securities has been somewhat limited. Past issuance has always happened in times of distress, as with the UK and inflation-linked securities first introduced in the 1980s. Costa Rica, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Greece and Argentina have been the main actors in the secondary market, albeit with a bespoke, complex design and an asymmetrical pay structure which didn’t entice investor’s appetite.

In these countries, what today we call GDP-linked bonds were most likely considered as warrants, in a bond option fashion. Most of the times a restructuring was taking place, and some of them have been crafted such that the principal was linked to commodity prices rather than GDP, making them a better proxy for some economies. What is significantly different, though, is the size of the issuance that Argentina and Greece decided to undertake in their time of crises.

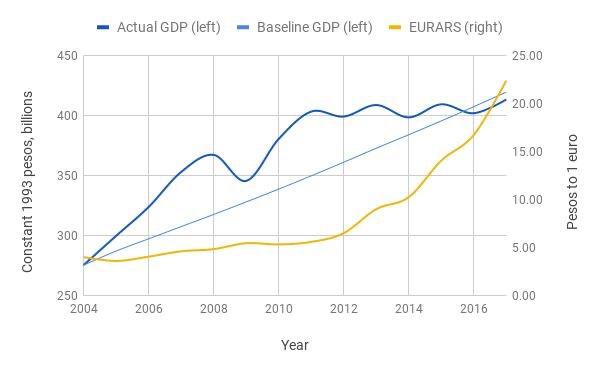

Argentina defaulted $94bn on its external debt in 2001 and, for this reason, constructed bespoke products called “sweeteners” to gain access to the capital markets again. These long-term bonds, between 2005 and 2010, could be swapped with some of the defaulted ones and not at all easy to trade: five kinds of them can be found, classified by currency of payment and different legal enforcements. The payments were triggered by real GDP being above a baseline trajectory and proportional to real growth, with a minimum and maximum cap. These bonds, in the end, proved to be extremely successful for the debt managers: external demands were invigorated, and the real growth could be translated in a 12,4% growth YoY for a decade. It is noteworthy to mention, though, that there was also the problem of data continuity, with Argentina changing the base year for GDP calculation in 2013: the bond documentation was far from comprehensive and gave rise to different interpretations on which GDP methodology to adopt for the coupon calculation.

Source: Bloomberg

The Greek experiment, however, was not as memorable when it was first issued in 2012. Most notably several complexities were added, such that the level of GDP was to be computed in nominal terms but the growth for the coupon rate at a real one. In the end, it was down to the sheer decline of the Greek GDP of the time that made the investment look like a far OTM call option. The coupon could float between a maximum and minimum value for capital preservation, but that was not enough to make the bonds lose 71% of their value. GDP now stands at 25% below the agreed value for 2018.

The payout amount related to the warrant can be calculated by multiplying the notional value by the GDP percentage index, which is found as seen below:

GDP Percentage Index = [Real GDP Growth rate – reference real GDP growth rate] x 1.5

With the relevant memorandum documentation placing some specific provisions, including the following:

- The GDP Percentage Index for any year will not exceed 1%;

- If real GDP growth for a given year is negative, or lower than the reference rate the GDP Percentage Index for that year will be zero.

At this point, it should also be highlighted that these warrants only accounted for 820 million euros at the time in comparison to the staggering 350 billion owed today.

Source: Bloomberg

Pricing: a heterogeneous overview

Pricing GDP-linked bonds is not an easy task, mainly because illiquid instruments are never easy to price accordingly. Liquidity, as far as it is a ubiquitous concept in finance, is yet to be modeled mathematically accordingly. Aside from this, we can understand that such bonds will be traded at a higher yield than a plain fixed income security – as convertible bonds would – but it is difficult to quantify the “GDP premium” determined by:

- The novelty premium: buying a security which has rarely been issued before. Can be tackled if there is a global coordination for these bonds;

- Liquidity premium: inability to create a functioning secondary market. Can be tackled by making large issuances from the beginning, as the UK did with inflation-linked bonds;

- Growth risk premium: uncertainty about the country’s future growth and its volatility;

- Default premium: inability for the seller to pay back the debt. Might be positive if GDP-linked bonds are able to make the overall debt more sustainable.

- Agency cost: if the institution of economic data can be reasonably trusted

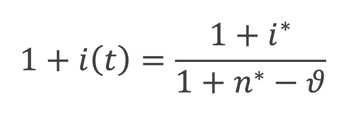

The yield on GDP-linked bonds is expressed with respect to the yield on risk-free fixed rate bonds , to the trend nominal growth and to the risk premium such that:

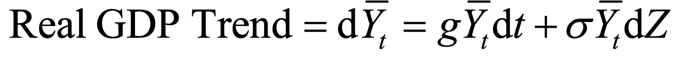

For instance, the real GDP trend can be determined by a geometric Brownian motion:

where represents the volatility of the GDP and g the expectable long run sustainability growth rate of the GDP.

However, the rub is still there: many academic papers have tried to give their own view on the premium. Assuming market completeness, Kruse (2005) develops a Black-Scholes type pricing model using a single-factor stochastic model when GDP follows a log-normal distribution, and uses it to estimate returns on GLBs for Indonesia and Venezuela. Miyajima (2006) develops pricing models for GDP-linked warrants using a Brownian motion for the GDP and Monte Carlo simulations on foreign currency and inflation conditions, studying the sensitivity of prices to exchange rate and GDP shocks. Kamstra and Shiller (2009) price their version of GDP-linked bond with a CAPM model of GDP growth on the S&P 500 and estimate a premium of 150bp. Borensztein and Mauro (2004) estimate risk premia using an equilibrium model and find premia in the range 35bp–370bp for different levels of investor risk aversion. Barr et al. (2014) use CAPM to estimate risk premium for Argentina close to 100bp.

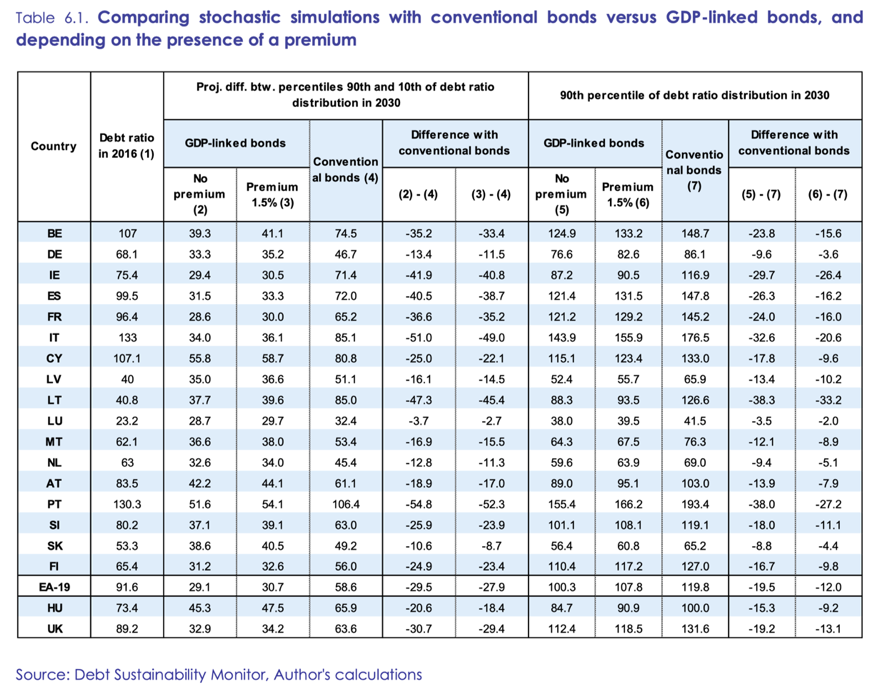

Stochastic simulations by the European Condition agree, overall, that GDP-linked costs would lower borrowing costs for European countries.

Source: Debt Sustainability Monitor

Advantages

As it can be seen from the cases of Argentina and Greece, it is evident that the countries issued these warrants when it was too late at the time where debt restructuring was the only option. What many argue is that the true benefits of issuing GDP-linked related instruments and particularly bonds is ex-ante and not ex-post. They should be viewed as a preventive measure against a painful restructuring scenario in case debt becomes too big to service.

These instruments, aside from the obvious debt stabilizing effect, can really ensure a good degree of debt related risk and cyclical management: As evident from the definition, the broadened use of GLBs by a country can substantially smoothen out both the downside of its economic cycle and reduce the probability of a disruptive, debt related crisis. The ability to reduce interest payments in recessions allows further flexibility regarding the fiscal policies decisions as well as, potentially, prevent the need for austerity measures, as seen in the case of Greece. If a sizable portion of their debt is auctioned off as GDP-linked, we might expect a smaller mismatch between the income gained from taxes and the overall amount of debt. Lower debt volatility, we ought not to forget, means lower real interest rate for all the sovereign debt issued.

The political side-effects are also relevant. GLBs can be a way for countries to follow a more responsible fiscal growth and give central banks more leeway on the interest rate decision, which should be their main duty. If the debt amount increases with a thriving GDP, politicians may be less inclined to promote tax cuts which are anti-cyclical in a growth instance. On the other end of the spectrum, politicians are still motivated to make the GDP grow for their re-election hopes.

A significant benefit from the investor side is portfolio diversification. These instruments allow all types of investors to get a stake in the economy while at the same time diversify significantly from the reference portfolio (80% US equities and 20% T-bills). The study by VOXEU shows that diversification through GLBs is far preferable than equities of a given country, given that we start from a reference portfolio. Specifically, the two driving factors of this are: a lower variance of nominal GDP growth than the variance of stock returns, and a lower correlation of nominal GDP growth with the initial portfolio. This study also allows us to visualize these gains, not only for the issuer but also for the investor. The blue bars indicate the decrease of Debt to GDP ratio over a 25-year horizon and 5% debt path. The red bars show the average potential decrease in the volatility of the reference portfolio by diversification through GLBs rather than equities. As it can be seen, GLBs can significantly bring down volatility by an average of 12% if the equities part of the portfolio was exchanged for GLBs.

Disadvantages

The main issue proposed by critiques regarding these bonds is the existence of a significant risk premium, as seen in the pricing section of this article, which in the past has made it an unworthy option for most economies, particularly the advanced ones. The premium, now, in the current macroeconomic environment of negative rates combined with uncertainty could possibly be even greater than it was before. Hence, making GLBs an option that is still not attractive.

Another reason, which perhaps has disallowed GDP linked bonds from getting traction, is the fact governments over the past years of consecutive growth were less inclined to issue these instruments whilst in a good economic environment, since servicing them would be more expensive than regular bonds.

The greatest complication in relation to these instruments is the political element attached to them, since there is a leeway for governments to define what constitutes GDP and GDP growth. Aside from the actual metric, the fact that fiddling with numbers and data manipulation can be done easily has created uncertainty surrounding their issuance. Many have argued that tax revenue could be a possible metric, but still has wide opposition.

Conclusion

There is a need to be constantly reminded of economic realism. Especially, in periods like these where the pandemic has forced all governments to implement unprecedented fiscal and monetary solutions. It is clear that the most battle scars against COVID-19 will be in the form of long term, macroeconomic vulnerabilities caused by debt. As outlined in this article, the risk reducing nature of GDP-linked bonds constitutes them as a possible tool for the alleviation of these vulnerabilities. This instrument should not be regarded any longer as a theoretical academic concept, but implemented in practice to realize the aforementioned benefits to both issuers and investors.

0 Comments