Introduction

Thames Water, the biggest water supplier in England, which was privatised by Margaret Thatcher’s government in 1989, is now facing a messy debt restructuring or even the prospect of a temporary renationalisation under the government’s special administration regime. In the higher interest rate environment, the company has been struggling to pay on its debt and has become the subject of public criticism over sewage pollution and mistrust of England’s privatised water system. Recently, investors’ refusal to inject promised equity into Thames Water and the parent company’s default on its debt have deteriorated already poor position of the water supplier. The latter has also threatened to wipe out the stakes of Thames Water’s nine shareholders, which include the Chinese and Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth funds as well as Canadian and UK pension funds. Shareholders are unwilling to invest new equity, much-needed for repair of Thames Water’s aging infrastructure, unless the water regulator Ofwat will approve a 56% real-terms increase in customer bills by 2030 and offer concessions on dividend rules and mitigation of fines. However, the government is facing growing pressure from activists calling for the renationalisation of the water system as private companies are not acting in the public interest. Ofwat is due to make a draft decision in June and a final ruling early next year, after which it can contested by companies.

Privatization of Water Supplies

Privatization of water supplies has been a common phenomenon among several countries for various reasons. With recent developments in the UK, specifically England and Wales, it is of interest to understand the motivation and framework behind it. Britain’s history of private water supply dates back to the beginning of the 19th century and gradually changed to public ownership towards the end of the 19th century, as in many other countries. During the 20th century, funding by the central government gradually increased. In mainland Europe, the public sector had a more central role from the beginning, apart from France where the private company Compagnie Générale des Eaux was established in 1853. In the case of England, since early on its system has been known for its poor quality of water, possibly caused by a lack of water quality enforcement systems and the responsibility to be with local governments, supported by central government subsidies.

By 1974, the UK parliament transferred the provision responsibility for water and sewage systems from local to regional water authorities (RWA) in England and Wales. At this point, 20 private water supply companies were allowed to serve 25% of the population along with the public ones. The establishment of said RWAs has been widely seen as a short-sighted measure leading the people to believe the central governments had assumed responsibility. But in fact, these frameworks allowed the government to use the water systems as macroeconomic measurements after the oil crises of 1974 and 1979, slashing funding by a third by the 1980s. However, a major mistake was made by the government, not counting for long-term regulatory changes, by joining the European Union which was tied to promises of increased sector investing. This past situation led to the need of extra financing, but the central government did not grant permissions to borrow enough funds due to political ideology.

Margaret Thatcher herself is often held responsible of preventing the RWAs from borrowing extra funds but in return putting the blame on them for not building enough. This eventually led to the privatisation of the water industry in 1989 justified by five highly debated objectives which were: increasing competition, reducing the size of the public sector, involving company staff, spreading share ownership, and releasing enterprises from state ownership. The last point is considered to have been the most important one for Thatcher’s government. Following the privatisation several regulations and regulatory offices were put in place to ensure quality.

There are a few positive aspects connected to the privatization of public companies. As mentioned before, this includes missing out on critical infrastructure upgrades, public regulations, and self-punishment.

First, public utilities are in conflict with pleasing voters. This is based on the fact that any increase in funding for new constructions or treatments has to be approved by city councils and commissioners who are focussed on keeping up their approval. This leads to a conflict as necessary investments are being missed out on as politicians aim to avoid increases in water bills, which might hurt their political standing among the general population. In other countries, such as the US, where the public can directly vote on such regulations, the issue is even more popular. A problem is that public utilities often have trouble generating the revenues required for important infrastructure updates, thus having to rely on rate hikes which in return are not approved by the public. On the opposite, privately held companies prefer stable revenues, having no issues with raising rates and improving the infrastructure to turn profits. In this case, private companies could act against the favour of the individual but in favour of the public who would not approve necessary improvements.

Additionally, competition among private companies incentivizes them to improve their operations and comply with standards. These kinds of incentives are missing among publicly owned companies. Research shows that public companies miss out on complying with a range of regulations, from inspection frequency to emissions and health levels of water (Teodoro and Konisky). These results could be based on the fact that public companies cannot regulate themselves as well, because the city council cannot quite shut itself down for missing out on regulations.

However, past and recent events have shown that privatization might look better on paper but faces tremendous difficulties in reality. While the motivation behind it was ambitious, the implementation failed to deliver. Even former David Cameron advisor Camilla Cavendish admitted in her article for the Financial Times that “Privatising water was never going to work”. Recent scandals with Thames Water, but also prior Southern Water incident, permitting harmful sewage into rivers and seas for several years, or the famous scandal of Flint Michigan in 2014 where a contaminated river had been tapped in order to save money, are proof.

A major issue is that privatized companies do not care enough about the public benefits. In fact, between 2007 and 2016, nine regional water companies had paid out 95% of their profits to shareholders and investments in critical infrastructure has declined to a fifth since the 1990s. In addition, proof shows that Scottish Water, which is still publicly owned, has invested on average about 35% more per household than English water companies between 2002 and 2018. Clearly, private companies neglect their original intention and are milking profits from important infrastructure.

Additionally, although theory suggests that private companies could be better regulated and would adhere better to safety and health standards, they do not. The reason does not lie in the failure of theory but in a disastrous implementation. Water companies are self-reporting any kind of incidents, which is supposed to foster transparency and honesty, and would spare the necessity of third parties to report, but research shows that only 77% of incidents are reported. Moreover, celebrities were the ones exposing Southern Water by taking probes and reporting results themselves, revealing the actual scale of the situation.

Last, ownership is very hard to tell apart and any conflicts of interests or outside influence by foreign investors and governments and thus threads to national security can hardly be identified. In the following, main investors and private water companies will be analysed and identified.

Main Players in Public Utilities: Water Focused

Originally, ten companies were privatised in 1989. Analysing the structure of each of them is complicated and often a network of subsidiaries with unclear ownership structure, adding to the issues of the industry. Famous investors in Thames Water included Australian Macquarie Capital Funds [ASE: MGQ], until 2017 when they sold their share. Estimates at the time said the fund made between 15.5-19% in annual rate of returns, however, it also faced criminal fines of up to £20m in 2017 for leakages affecting the Thames. In September 2021 Macquarie re-entered the UK private water infrastructure market by investing £1.1bn in equity into Southwestern Water group committing to delivering reliable services and protecting and improving health of rivers and sea.

But Macquarie is not the only foreign investor of UK water companies. Other well-known financial service companies include Blackrock [NYQ: BLK], Lazard [NYQ: LAZ] and Vanguard (Severn Trent, United Utilities and South West Water), Germany’s Deutsche Asset Management [XETRA: DWS] an US based Corsair Capital (Yorkshire Water). JP Morgan Asset Management [NYQ: JPM] owns 40% in Southern Water, and Australian Colonial First State Global Asset Management owns stakes in Anglian Water, Severn Trent, United Utilities and South West Water. Apart from these companies there are numerous other foreign investors from the Arab Emirates, Kuwait, China and Australia (Thames Water), a Malaysian company (Wessex Water), and Cheung Kong Group (Northumbrian Water), an in the Cayman Islands registered fund associated with Hong Kong’s richest person, involved.

The role and influence of foreign investors can be understood best when looking at the Thames Water external shareholders. Canada’s largest shareholder pension fund, Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), holds over 30% in the water and sewage systems company. The fund had net assets of $129bn at the end of 2023 and invested in Thames Water in 2017. The investment was made using several investment vehicles based in different locations, such as among others Singapore. Close to 10% in the company is held by Infinity Investments SA, a subsidiary of the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority who invested in 2011. The fund also has done an $800m investment into Statoil, a Norwegian natural gas transport company. In 2012, China Investment Corporation, one of the biggest sovereign wealth funds in the world has acquired a 9% share in Thames Water. Further foreign institutional investments include Queensland Investment Corporation, a government owned Australian investment firm (5.3%), and Stichting Pensioenfonds Zorg en Welzijn, the second largest pension fund in the Netherlands.

It becomes evident that the foreign investments into Thames Water are making up the majority of external investors bringing up the question whether they could possibly pose a threat to vital infrastructure in the UK and whether their interests align with the UK government and general public which is directly being affected by the company’s operations.

Public to Private to Public?

In recent years UK government and opposition parties have faced huge pressure from activists who are criticising the privatised water system as they claim it is not acting in the public interest. According to a YouGov poll in June 2023, 69% of people believe water companies should be nationalised. This growing pressure comes from several reasons. Firstly, more than 70% of the privatised water industry in the UK is owned by foreign investment firms, private equity, pension funds and, in some cases, businesses based in tax havens, which raises concerns about the public utilities companies acting in the interest of shareholders rather than general population. Secondly, people are not happy with the water bills which increased by 7.5% to an average of £448 last year. Consumer groups said the increase of £31 a year could be dramatic for the 20% of customers who were already struggling to pay. Here a logical question arises: where the water bill money goes? In the 34 years since England’s water was privatised by Margaret Thatcher, water companies paid on average £2.1bn in dividends every year. The big nine companies, being debt-free before privatisation, have accumulated £54bn during this period. Researchers claim that debt is used by water companies to pay dividends, and debt in turn has to be repaid with interest. It turns out, £1.5bn of customers’ money is spent yearly by paying interest on these loans.

On the other hand, in a public system as the one that exists in Scotland, the water companies still take on debt, but money does not leave the system through dividends. Despite already high bills, Thames Water has recently asked to be allowed to raise bills by 56% by 2030, including inflation, which accounts to around £262 per household. However, the Consumer Council for Water has warned that the increases will be unaffordable for many households and there is a growing campaign calling for non-payment of bills. Furthermore, there is a widespread anger over sewage pollution as 47 overflows owned by Thames Water discharged raw sewage more than 100 times last year. These accidents showed that companies had not invested enough in repairing and replacing infrastructure.

The government recently ordered the industry to invest £56bn in the infrastructure facilities to stop the millions of litres of raw sewage being discharged via storm overflows into rivers and seas. Experts said that analysis of NHS hospital admissions linked to water-borne diseases, including dysentery and Weil’s disease, had risen by nearly 60% since 2010. Concerns over the future of Britain’s biggest water provider reached a peak in April 2024, when investors refused to inject £3bn of much-anticipated equity, despite nearly a year of negotiations with the water industry regulator, Ofwat. Although public is hoping for nationalisation, the government and Ofwat are determined not to bring Thames Water back under government control as it will potentially pile up more pressure ahead of the general election later this year.

Currently, there is a growing trend in favour of nationalisation as people claim it will result in better service. Firstly, public companies can borrow money at lower interest rates as they receive state guarantees. Secondly, they do not have to pay shareholders and, therefore, can reinvest more profits in development of the required infrastructure. Last but not least, the water industry is essentially a natural monopoly which benefits from economies of scale. The average fixed cost, and thus, average total cost of supply fall as more customers are connected to the network. It implies that average household bills can be lower, and the industry can benefit from higher levels of capital investment funded by the government. Nowadays, there is the overall trend towards renationalisation of public utilities companies. According to researchers, 311 cities in 36 countries renationalised water services between 2000 and 2019. Three countries accounted for the majority of cases: France with 109, the US with 71, and Spain with 38, while in Italy, Denmark and Germany the market share of public utilities has also begun to increase.

However, there are many concerns that the cost of taking the UK water industry back into public control will be enormous and customers will bear a huge part of it. The court rulings are the key factor in estimating the cost of renationalisation of the water companies. David Hall, a visiting professor at the Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU) at the University of Greenwich, said previous court decisions were clear that the basis for compensating shareholders was decided by parliament on a case-by-case basis, taking account of a range of relevant matters, including public interest objectives, and the particular circumstances of each case. He also said that courts had consistently confirmed that public policy considerations were fundamental, and there was no general right for investors to be paid full market value as compensation. Estimates of the cost of renationalising the UK water industry range from £14.7bn, estimated by the PSIRU, to £90bn if company debts are included (from the Social Market Foundation research). However, many experts claim that the real valuation should be much lower than £90bn as Thames Water is highly likely to default on some of its debts and their market value will decrease sharply due to the deterioration of the credit rating of the company.

Furthermore, reputation damage from the sewage pollution scandal and investors’ refusal to inject much-needed equity in the company might lead to the fall of the share price, and thus, equity value of the company. The valuation also depends on the inflation fluctuations as it is ruining the biggest water supplier with excessive loan interest payments. However, it is important to mention that nationalisation was never fully sponsored by cash from taxpayers’ pockets, on the contrary, governments usually pay the shareholders by issuing the government bonds. It was the case with the nationalisation of the railways industry in 1947, when government bonds were issued to pay the shareholders of the under-capitalised companies. Therefore, if Thames Water was nationalised, the only cash cost to be paid would be the cost of the interest on the new bonds issued, which could be paid out of the company’s own cashflows, free from paying dividends to shareholders in case of public control. In other words, nationalisation of Thames water is a totally viable option as it can be done by paying investors with government bonds and using the money, which the water industry already pays to shareholders.

Despite for now the government is determined not to bring Thames Water back public, different scenarios are possible. If after all the parliament will be forced to renationalise, the closest example may be Railtrack, the rail infrastructure company, which was renationalised as Network Rail. It faced similar public criticism over safety issues and was eventually taken into special administration in 2002, with government paying £500m to shareholders. Other example can be found in the case of Northern Rock, where the shareholders were paid zero compensation when the bank was taken into public ownership during the 2008 financial crisis. However, the most famous case of company being taken back public from private occurred in France in 2008, when socialist mayor Bertrand Delanoe ended the contracts with the two firms that had operated Paris water distribution systems since 1985 – Veolia on the right bank of the city and Suez on the left bank. Publicly owned Eau de Paris, which took over from 2010, has since become a model for many French and foreign cities and a threat which leaders now use to force a decrease in prices. Indeed, the case was a great success as in Paris water bills fell by 8% in 2011. The move was followed by other French towns with a combined population of about 1.4 million people – including Rouen, Saint Malo, Brest and Nice. An October 2013 study of French water prices by consumer group UFC Que Choisir found that the cheapest water rates were nearly all run by public bodies, while those with the most expensive were mainly run by Veolia or Suez, that has led to nationalisation of water supplies by other countries and severely challenged the position of private utilities companies. Italian population rejected further water privatisation in a 2011 referendum, while Berlin retook public control of its water in 2013, buying back stakes in Berlinwasser from Veolia and utility RWE. In late 2013 the Right2Water petition organised by public water unions gathered 1.9 million signatures against water privatisation which resulted in the European Commission’s decision to remain neutral on national decisions about ownership of water.

Thames Water Case Study: History and Present

Thames Water Utilities, also known as Thames Water, is a British private utilities company responsible for the water supply and treatment in London, and some other regions of England. The company was established in 1989 during the privatization of the water industry in England and Wales and went on to become the UK largest water and wastewater services company serving over 15 million customers currently. Initially owned by a consortium called Thames Water Authority, it was then sold to RWE AG [FWB:RWE], a German utilities company, in 2000 for €7.1bn.

In 2006, after a competitive bidding process, a consortium called Kemble Water, led by one of Macquarie’s Infrastructure Funds, acquired the company for £8bn. More specifically, the Bank bided £4.8bn and agreed to assume £3.2bn of debt. The deal value came as a surprise to many as the market expressed concerns about the company because of its reputation. While serving over 13 million customers at the time, the company was undergoing a period of scandals and fines that came as a result of missing targets to reduce leaks, usage restrictions the users faced, as well as problems with the quality of the water.

Following the acquisition, Macquarie formed a Whole Business Securitisation (WBS), a structured finance product where the company issues secured notes which are backed by a pool of income generating assets that make most of the revenues of the business. Compared to standard corporate credit, notes issued through WBS structures have higher ratings and receive more favourable financing conditions. For the companies, this allows them to have a lower cost of funding. Through significant leverage, the firm managed to continue growing, while paying substantial dividends to its owners, but the service did not improve. After a series of gradual sales, in 2017 Macquarie Asset Management was able to divest completely from their investment in Thames Water. However, since then, the Australian investor has been facing criticism over Thames Water current leverage levels, the increase in leakages and pollution, along with the returns the firm perceived over their holding period.

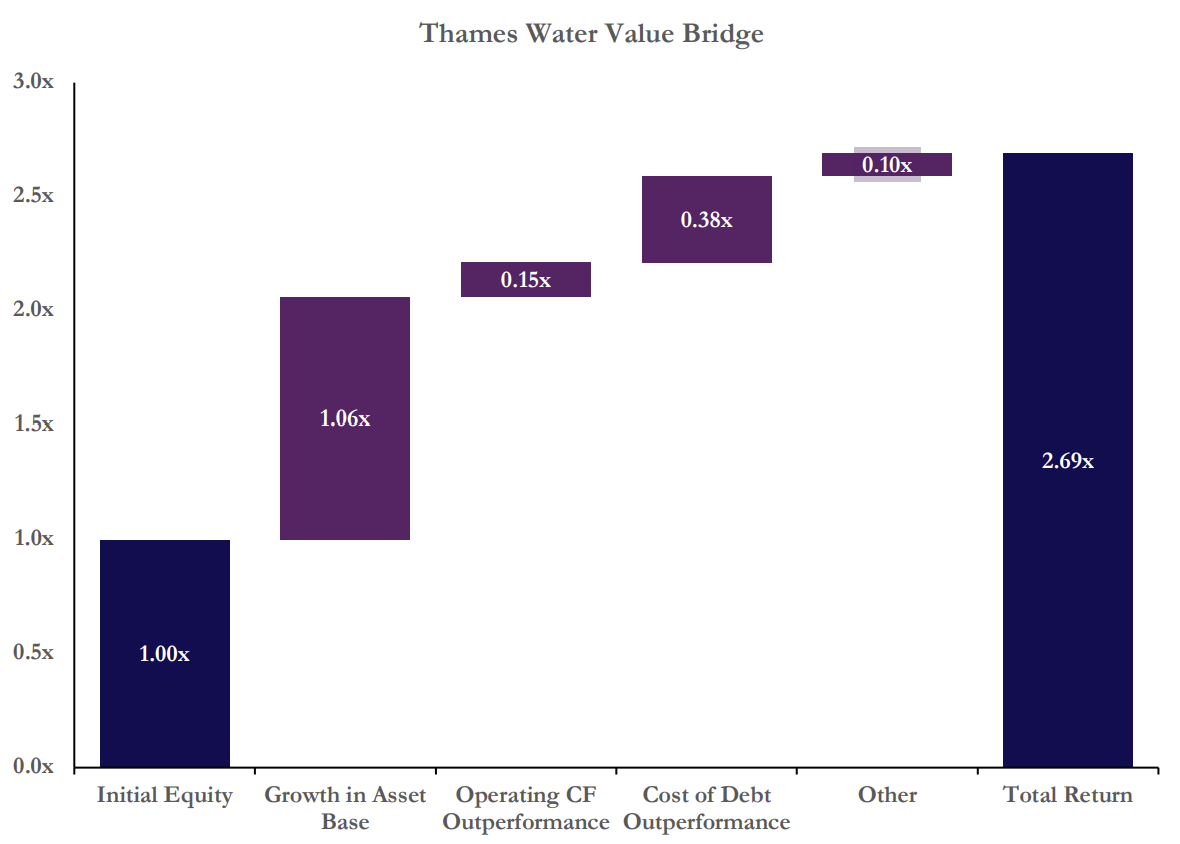

Throughout Macquarie Asset Management (MAM) holding period of 11 years, from 2006 to 2017, Thames Water underwent through significant transformations. According to Macquarie, on an operational level, the security of supply increased from 22 to 100. Also, regarding leakages the company had the second-highest leakage improvement ever at industry standards with leakages dropping from 860 million litres a day prior to MAM investment, to over 200 million litres in 2016. On a more financial note, Thames Water debt increased from around £3.5bn to +£10bn. Roughly, the increase in debt came from £2.2bn that was used to fund the transaction and £4.5bn that were issued. Moreover, throughout the period the firm generated a cumulative EBITDA of £11bn, so all over MAM holding period Thames Water had around £15-£16bn of total funding. The funding was mainly used to invest in CapEx, as over £11bn were invested, plus around £4bn was paid in interests and investors received £1.1bn in dividends. While the dividend amount seemed high and created controversy at the time, MAM claimed that a £100m a year return on a £2.3bn original equity investment accounted to a ~5% yield of the original equity. Furthermore, this investment generated a gross 12% IRR and a gross 2.7x MoM return for MAM. Regarding the IRR, the 12% is a good figure as it outperformed the industry standard for utilities operators of 10%.

Source: Macquarie, Infrastructure Investor, BSIC

Nonetheless, while on paper the investment was ideal for MAM, it was not necessarily the case for users nor the water sources. On March 2017 Thames Water, while still being owned by Macquarie, received a record £20.3m fine for dumping 4.2bn litres of sewage water into the Thames in the period between 2012 and 2014. Moreover, the firm also was fined £1m for repeated discharges of sewage residues into the Grand Union canal in Hertfordshire in 2012-2013.

In March 2017, Macquarie reached an agreement to sell its final stake in Thames Water. They sold their last 26.3% stake in the company to a group of retail investors that included OMERS and the Kuwait Investment Authority. Since then, ownership has changed between hands from time to time, and as of June 2023 some of its shareholders included OMERS (31.8%), USS (19.7%), Infinity Investment (9.9%), British Columbia Investment Management (8.7%), Hermes GPE (8.7%), Queensland Investment Corporation (5.4%), Aquila GP (5.0%), Stichting Pensioenfonds (2.2%), among others. Nonetheless, the change in ownership didn’t change the operational and financial situation of the company, and the existing troubles persisted.

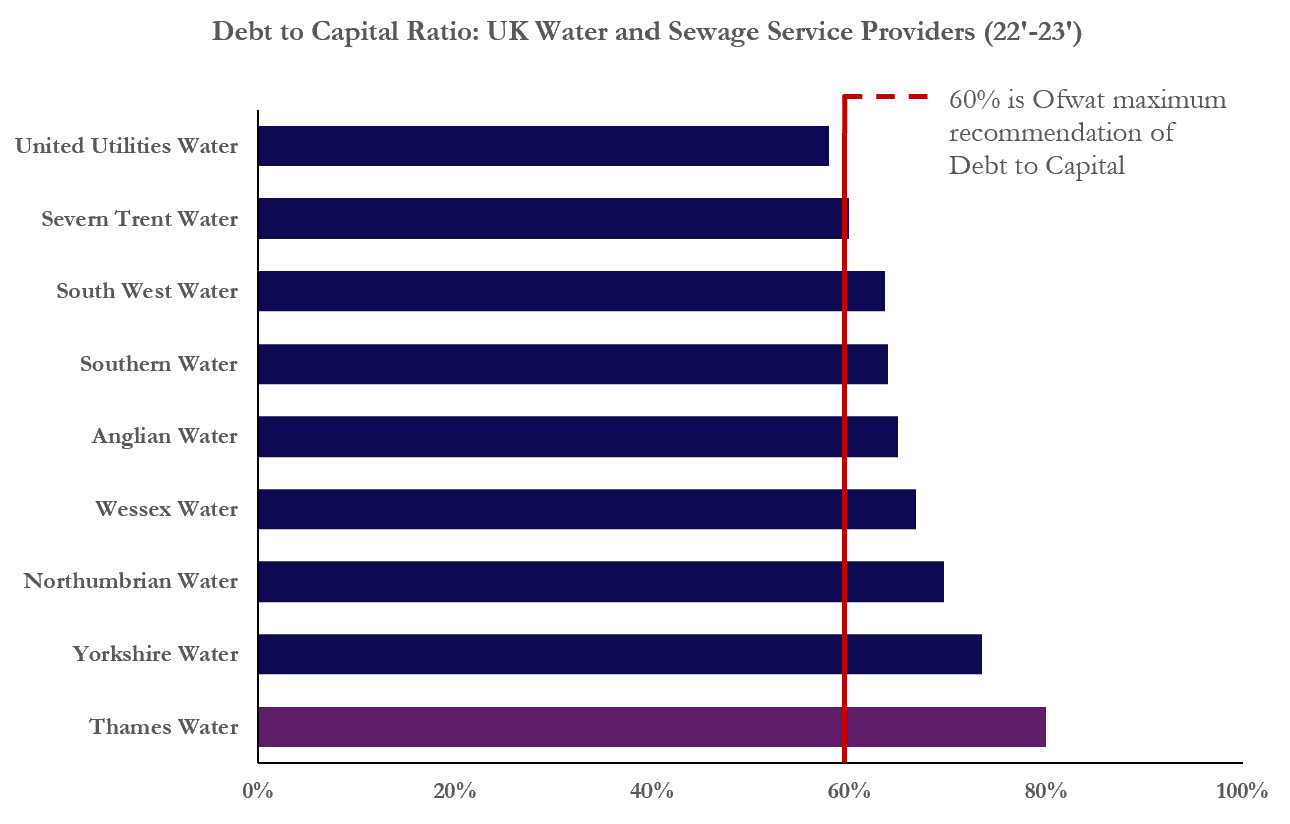

In an attempt to improve the company’s financial situation, the most recent consortium that took over Thames Water has not taken dividends since 2017, however its total debt and interest payments have increased significantly. On the contrary, they even invested an extra £500m of equity into the company during 2022 with the hopes of turning the company around, but their efforts were not enough. As of 2023 total debt amounted to over £15bn, with interest payments accounting for more than half of the company’s EBITDA. While the water utilities industry is known for its high leverage, compared to its competitors and to the standards that the Ofwat sets, Thames Water is the most over levered company reaching above an 80%. Moreover, in June 2023 the company CEO, Sarah Bentley, resigned following sewage spills and the overall bad performance of the company over the last years.

Source: The Guardian, Ofwat, BSIC

*Data from: Mar 23’: Severn, Utilities United, Sep 22’: Thames, Wessex, Yorkshire, Mar 22’: Others

While during the second semester of 2023 investors agreed to invest another £500m into a form of loan to the parent company of Thames Water, Kemble Water, troubles persisted. Not only the company announced in December that they might not be able to pay £190m in loans due in late April of 2024, but also the total debt of the company had increased to £18.3bn as of March 2024. Moreover, Kemble Water claimed that equity holders were willing to inject a further £3.25bn into the company over the next years, but under the condition that Thames Water would get their desired regulatory outcome from Ofwat. The company was asking Ofwat to approve a 56% real-term increase in bills by 2030 as well as more leniency on dividend rules and fines for pollution and service failure.

However, in March 2024, Kemble announced that they expect Ofwat to not budge after more than a year of discussions. Consequently, they decided to backtrack from the 2023 £500m investment promise made, and alone the £3.25bn needed by 2030. Investors such as the Chinese and Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth funds, as well as the UK and Canadian Pension Funds, claimed the company was un-investible. Moreover, investors such as USS and OMERS already begun to write down their investments, and all the shareholders are expected to take an initial estimated loss of £5bn. One partner at a law firm advising one of the company investors said that Thames Water is fully dependent on Kemble’s ability to raise further equity from investors to be able to deliver on its business plan. However, Kemble’s default raises serious questions about the future fundraising capabilities and the company’s long-term viability. Hence, Ofwat may need to intervene.

On April 5, 2024, Kemble Water sent a formal notice to its bondholders informing them that it has defaulted on its debt, potentially leading to a large restructuring of one of Britain’s largest water utility companies. The bond was sold by Kemble Water Finance, which is one of the companies in the labyrinthine corporate structure that was built by Macquarie when they acquired Thames Water. Moreover, the £15bn of debt that is held by Thames Water, the ServCo, which seats below Kemble, should be unaffected by the default. The default threatens to eliminate the stakes of the Thames Water shareholders, which as shown before, include Sovereign Wealth Funds and Pension Funds. It was revealed that Kemble’s creditors, which include two Chinese state-owned banks, along with others, were involved in a stand-off over potentially extending the £190m loan that is due at the end of April 2024. However, as the company didn’t manage to raise more equity, there was no extension. Aside from the Chinese state-owned banks, another of the lenders to Kemble is Macquarie, its previous owner. Through loans that are managed by one of the asset management divisions of the Australian institution, they lent a total of around £130m to Kemble Water Finance in 2018 and 2020.

Kemble creditors could potentially look to take over the company via a debt-for-equity swap, however, the substantial investment the company requires doesn’t make the option very appealing. Moreover, Kemble’s £400m bonds are trading at around 15% of their face value, indicating a complicated situation for the debt investors. Other potential solutions include passing the company to a Special Administration Regime (SAR) that with the help of external administrators would seek new investors, or a potential renationalization of the business. Lately, there has been amendments to the SAR that leave shareholders with the possibility of having their ownership of the business removed, while still being liable for the debt. Hence, it is a scenario the company will try to avoid. Furthermore, some analysts claim that the messier the debt restructuring procedure is, and the less efficient the decisions taken are, the more likely the company is to face a nationalization.

The only thing that is clear is that Thames Water needs billions of pounds to maintain and improve its aging operations, as well as to address its leakages issues. Thames Water still has over £2.4b in cash and equivalents which will allow them to continue operating for at least 15 months even if Kemble goes into administration.

Sources: Financial Times, JP Morgan, Company Information

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current situation of Thames Water shows the complex challenges faced by privatized utilities in the UK. While there are arguments both in favour and against privatization, the current situation the water and sewage utilities companies face in Britain leads many to advocate in favour of a public model, as many countries have reinstated. A YouGov poll made in 2023 found out that 58% of Conservative votes thought water should be brought to public control. However, neither the Conservative, nor the Labour party, which is the most likely to win the upcoming elections, seem to have any interest in undertaking the costly and complex renationalization of the water industry, which comes with a significant political cost. Moreover, there are lessons for investors to learn. While all investments carry risks, shareholders of regulated companies that provide essential services must take an active role in ensuring their assets are well managed, else consequences are not only financial, but environmental and have an impact on society.

0 Comments