Introduction

In this article, we will try to provide an insight on green bonds, a quickly growing new star of impact investing trends in the world. A total of US$580bn in green bonds were sold up to the year 2018, and at least another US$170bn more are expected to be sold this year, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Despite starting from a simple idea, green bonds are quite complex in their common regulation standards, or lack thereof, and despite aiming to do good, sometimes may be used for “greenwashing” purposes.

We aim to provide an outlook on currently adopted and proposed standards, market volume and trends, current challenges and limitations which both the issuers and investors must face, the existence of a hypothetical negative pricing premium and potential consequences of a widely discussed “Green QE”.

What are green bonds and how are they used

Environmental, social and corporate governance criteria have been on the radar of millions of ethically-concerned investors, determining their decisions and capital allocation in the last decades. For many, it meant excluding firms with high carbon emission, poor management of land, contaminating wastes or producing a nuclear weapon from their portfolios. We could see how companies can be affected when their ESG outlook changes rapidly on an example of e.g. Volkswagen or BP. For other environmentally and socially conscious investors it’s been investing in its project-oriented relatively new addition to the market – the green bonds.

“Green bonds” or “climate bonds” are plain-vanilla fixed income products raising funds from investors looking to invest in environmentally beneficial projects, aiming to provide a market-based solution to mitigating climate issues. They possess the characteristics of any other bonds – an issuer, face value, yield and maturity date, but on top of that, green-labelled bonds usually specify how the bond’s proceeds will be used within a specific project.

This may indicate a strong negative premium, as the issuer is giving up his freedom in the use of proceeds, however, according to Morgan Stanley’s “Behind the Green Boom” October 2017 research: “since late 2016, green bonds have outperformed their conventional counterparts, both in absolute terms and on a risk-adjusted basis.”. We discuss the existence of the premium later in the article, but the non-pecuniary motivation is still the strongest amongst investors looking to allocate capital into climate bonds reflecting a quickly growing new trend in global finance.

The Green Palette

Despite the good-faith “environmentally beneficial projects” is a very subjective term. Green can have many shades as no universal standard currently exists and investors’ views differ when it comes to what “green” means when choosing new projects. For example, the proceeds of bonds have already been used to finance strictly standardized renewable energy farms, but also a $150m 2000 megawatt coal-fired powerplant in China, labelled as “clean” coal, as it happened in 2015.

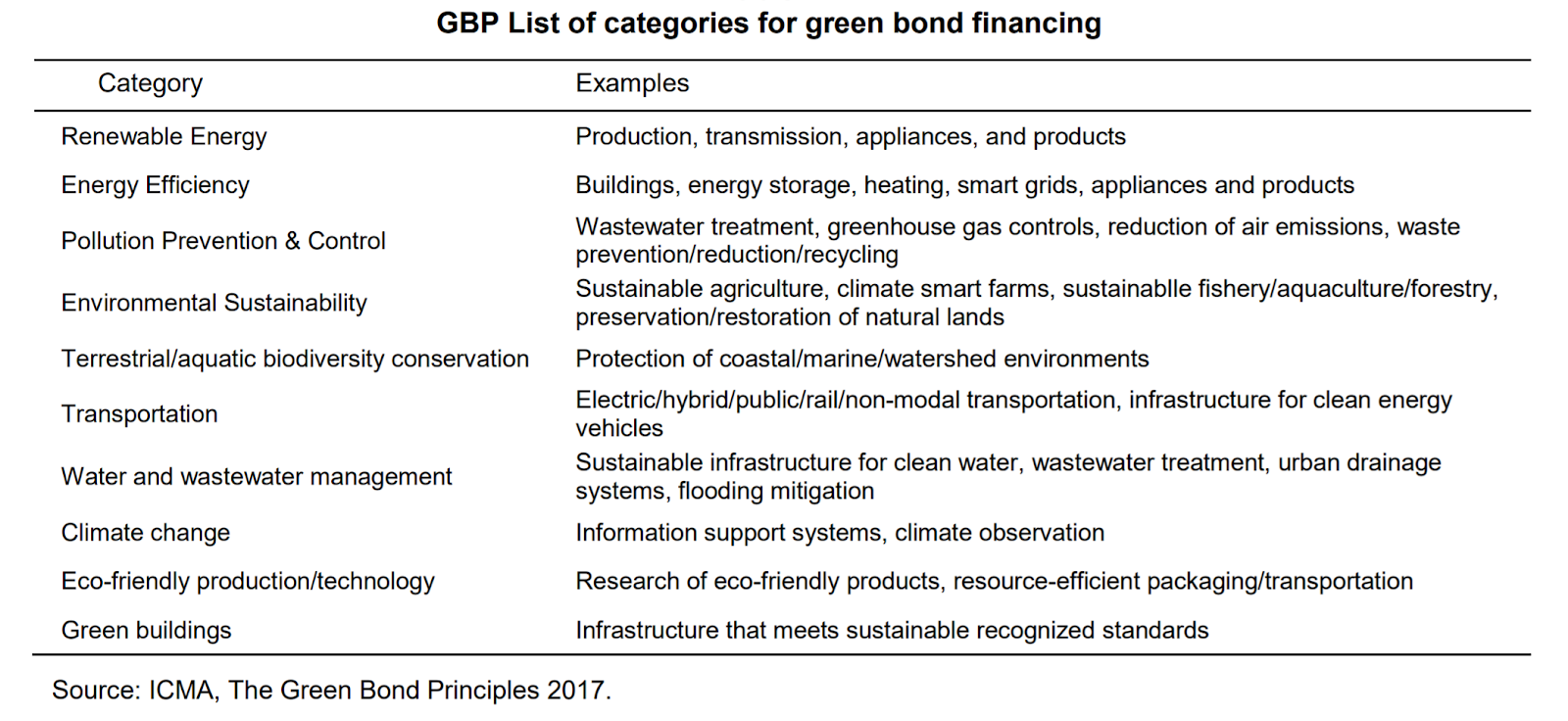

This is one of the biggest challenges that green bonds need to face right now and major issuers try to aid investors in making a conscious decision by voluntarily aligning with external standards. Currently, the most popular frameworks followed by issuers are the Green Bonds Principles released by the International Capital Markets Association (table 1). GBP consists of four main components:

- Use of proceeds

- Process of evaluation and selection

- Management of proceeds

- Reporting

According to ICMA, 63.6% of green bonds issued in 2018 were in line with the GBP criteria, from just 10.3% in 2012, becoming a de-facto current market standard.

Source: ICMA

A more rigorous and strict in its requirements is the Climate Bond Standard, created by the Climate Bond Initiative. Unlike GBP, the CBS also includes a certification scheme, for which the issuer must meet both pre-issuance and post-issuance criteria. For issuers, it’s not a matter of choosing between the two, as all Climate Bond Initiative certified bonds are implicitly aligned with Green Bonds Principles. As long as all requirements are met and verified by an external verifier, the issuer can obtain a certification, which costs 1/10th of a basis point on top of the cost of the external review. (CBI, 2018a). CBI also publishes its post-issuance reporting standard; however, in 2017 it reported that only 27% of green bonds were in line with its post-issuance reporting guidelines.

As previously stated, investors care for non-pecuniary motives as well and thus very often carefully analyze how bonds proceeds are used in specific projects. Despite a lot of credit rating agencies and accounting firms serving as second-party verifiers, a new wave of environmental consultancies and research institutes has been getting involved with writing these opinions. This may pose a risk to the “greenness” of the bonds, as these second-parties usually get paid for providing their opinions and it is said that when it comes to regulations, we are currently in a similar state as with the credit agencies before 2008 crisis. Thus, a new push for regulating these second-party verifiers is gaining momentum.

A wannabe leader in both establishing a liquid market for and standardizing the green bonds is the European Union. Following the Paris Climate Agreement and the G20 Hamburg Climate and Energy Action Plan, in July 2017 the European Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance has published a roadmap with the path towards certifications in EU sustainable finance market. Since it’s a political project and assuming that public funds are insufficient to achieve its low-carbon economy goals, establishing a liquid climate bonds market is a logical next step for EU politicians. Currently the EU Technical Expert Group (EU-TEG) is finalizing its work on common EU Taxonomy, i.e. a classification system introducing sector-specific criteria and defining areas where investments are most required, facilitating choice and transparency for investors, while also working on an official EU Green Bond Standard to foster more trust and confidence in green products.

However, at times the EU propositions go as far as including increasing the demand for climate bonds through bank equity capital regulation, i.e. lower capital requirements for green bonds. This, combined with potential additional privileges in financial regulations towards green bonds due to it being a political project, may unfortunately lead to a creation of a bubble, as it can create an environment resulting in overinvestment and undercapitalization, which in the end, after the burst of such bubble, could result in more cautious and lower capital allocation towards green projects from institutional investors in the future. When designing a long-term policy, such risks should also be taken into consideration.

The Inception

In 2007, a United Nations agency released a concerning report on climate change settling the debate regarding the impactful role of the human factor in global warming. This report along with the growing concerns about environmental sustainability prompted several pension funds to contact the World Bank Treasury. What they asked for was a way to identify and invest in climate projects.

After a year, in late 2008, the World Bank issued the first green bond, establishing the beginning of a new era of eco-responsible investing. To substantiate the validity of these projects as solutions to environmental concerns, the Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO) quickly got involved as a scientific third-party and provided an expert opinion. Since 2008, the Green Bond market has grown tremendously, bringing investors, policymakers as well as scientists together. This market has shown that financial returns and environmental sensitivity can coexist.

Volume Growth

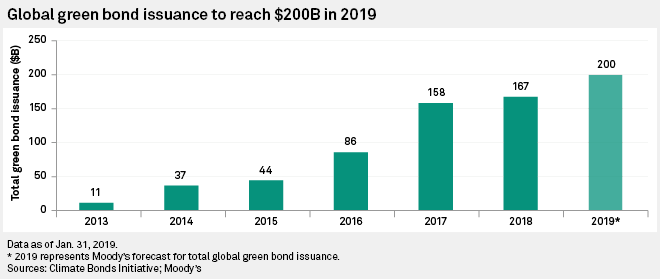

The volume of green bond issuance surpassed the $200bn benchmark, as of the end of Q3, making 2019 by far the most successful year in terms of volume growth, after stagnating one year earlier. The year on year issuance is so far up by a staggering 87%. To put these numbers into perspective, since the first green bond issuance, the total volume amounts to $500bn.

Source: Moody’s

When it comes to currencies, in 2018 Euro has surpassed the US dollar with regards to its share in annual market volume, having 40% and 31% respectively.

It is also worth mentioning that this huge demand shift into the green bond market is also reflected by the regular oversubscription rate of 2.3 in Europe and 2.8 in the United States, meaning that it is the climate bonds supply that might have been bottlenecking the growth between 2017 and 2018.

Issuers

Countries

Europe remains the leader in green bond issuance with 145 issuers in the market, which accounts for a third of the global total. Since 2018, China has started emerging as a major player. Volume growth is heavily dependent on the expectation that China will be able to accelerate growth in green finance in Asia. This is an almost certain scenario since in 2019 Chinese policymakers produced substantial regulatory clarity and development.

Issuer Types

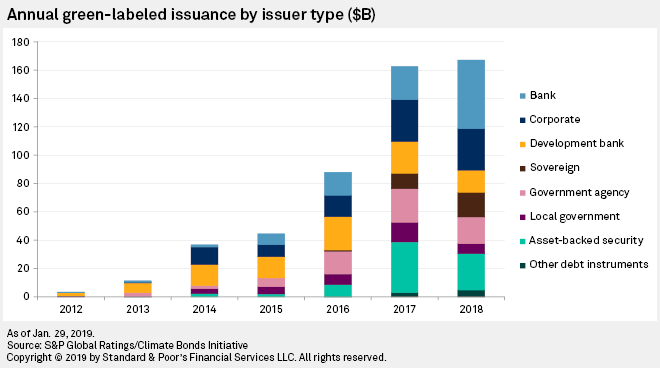

The composition of issuers in the market has not changed substantially over the past five years. The most apparent changes between 2018 and 2019 are the shrinkage of financial and non-financial debt issuance and the twofold increase of sovereign issuers.

It is worth noting, that until 2012 when French municipalities started issuing their own green bonds, the only entities issuing climate bonds were supra-nationals. The corporate and sovereign issuances quickly followed suit starting in 2013 and as the market has been maturing, the structure is now reverted, with financial institutions and corporations currently making up for the majority of issuances.

Source: S&P Global

Worth Mentioning Case Study: TenneT’ biggest corporate bond of the year

TenneT is a leading European electricity transmission system operator (TSO) of which around 805 of investments are related to the energy efficiency/renewable energy sector, with a primary focus on wind and solar energy. It is also significant to mention that TenneT has been recognized in Environmental Finance’s bond awards.

In May 2019, TenneT announced one of the biggest green issuances of the year. The deal is composed of two tranches: The first one requires a €750m investment and has a 16-year maturity and a 2% coupon. The second one requires €500m and has a 10-year maturity and a 1.375% coupon. This project pushes to connect offshore wind projects in the Netherlands and Germany to the onshore grid. This is a massive step forward towards the energy transition, which has gained great interest from investors. The investor’s appetite for this deal is reflected by the fact that it has been highly oversubscribed. Specifically, some orders amount for more than €5bn.

This particular project is supported by institutions like ABN AMRO, Barclays, HSBC, NatWest Markets and SMBC Nikko. The credit rating of the project is A3/A- Moody’s/ S&P Global.

Market Growth Projections

The exponential market growth year on year has formed a rising trend that is expected to continue in 2020, with forecasts suggesting the issuance volume of green bonds to reach ~$400bn. However, it should be mentioned that critics have raised concerns regarding the existence of adequate contractual protection, or rather, the lack thereof, which can adversely affect the future growth of this market.

Contractual protection in the green bond market is absolutely crucial for the investors’ financial safety against “green defaults”. Green defaults can arise as a result of the issuance proceeds not being utilized in the way promised by the issuer or of the “green” project changing in a way where it no longer satisfies the aforementioned green standards.

The absence of the essential clarity required for the investors’ contractual protection is a factor that has in the past, and certainly will be the reason why many investors refrain from entering the green bond market. The Climate Bonds Initiative has begun taking some steps towards enhancing contractual protection and green project report quality, making the future outlook positive for the market.

Trade-offs and pricing

Although at first glance, to a cautious fixed income veteran investor, such limitation in the use of proceeds stemming from adopted standards, may seem as a risk or yield trade-off, with potential additional political-correctness and ineffective government subsidizing schemes that should be priced in.

In fact, some studies, such as Zerbib’s paper, suggest there is a small negative premium, of -2 basis points on average, for the entire sample and EUR and USD bonds separately, with this premium being more pronounced in low-rated bonds.

Other studies, like Bachalet et al., find that matching green bonds with its closest “brown” bonds counterparts results in green bonds having actually higher yields, lower variance, and more liquidity, which can be explained by further analyzing the type of issuer and whether there is post-issuance verification. The study finds a peculiar feature, that green bonds issued by institutional issuers have higher liquidity with respect to their brown bond counterparts and negative premia before correcting for their lower volatility. On the other hand, climate bonds from private issuers have much less favourable characteristics in terms of liquidity and volatility but have positive premia with respect to their brown counterparts, unless the private issuer commits to certify the “greenness” of the bond.

Other interesting findings by researchers include that green bond returns are strictly correlated with corporate and treasury bond returns, whereas they weakly co-move with stocks and energy commodities.

The literature tends to be divided and differs greatly depending on the sample choice, currency and whether the analysis regards the primary or secondary market, but with the market volume growing quickly, we can expect more robust data and studies to come up shortly.

The Green QE

With the rise of green bonds, a new idea has been gaining momentum when discussing central banks’ involvement in the markets – a green QE.

Proponents of these ideas suggest that ECBs involvement in European green bonds market would positively impact climate change, reducing the global warming effect and helping fulfil the 2100 temperature increase goals [12]. Some even suggest a punitive “haircut” to bank collateral with a higher carbon intensity, suggesting that combined with green asset purchases such tilting approach could reduce carbon emissions in the Eurosystem’s corporate and bank bond portfolio by 44%.

In a recent speech, executive board member of the ECB Benoît Coeuré said that the ECB has bought green bonds under previous rounds of asset purchases. By late last year, it had purchased 24 per cent of the €48bn pool of eligible green public sector bonds and 20 per cent of the €31bn pool of eligible green corporate bonds.

However, further expansion seems unlikely as the market is still relatively small, at around 5% of all Eurozone debt issuance. Recently, current ECB president Ms Lagarde said that the ECB still awaits the EU taxonomy before making decisions on green bonds becoming a more significant part of the asset purchase program.

Tags:

Green bonds, ESG, climate bonds, bonds, money, environment, business, World Bank

0 Comments