Introduction

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and subsequent Great Recession pushed the US Federal Reserve to deploy two main tools of monetary interventionism:

1) Quantitative Easing (QE)

2) Reduction of the federal funds rate to unprecedented historical lows

The Federal Reserve began purchasing both sovereign and corporate bonds in mass amounts as part of its quantitative easing programme, progressively pumping around 4.5 trillion USD into the financial markets in an effort to stimulate growth and lessen the odds of a lasting economic depression. QE has undoubtedly increased the liquidity of financial markets and furthermore helped the fiscal expansion programme that lasted for the 8 years of the Obama presidency which has drastically increased the public deficit, amplifying public spending. QE “helped” the Treasury keeping interest rates on debt artificially low (that would have risen substantially without monetary intervention).

During these years of QE the Sovereign Debt/GDP ratio increased from 67% to 105% while the yield on 10-Year US Treasuries dropped from 3.8% in 2008 to around 1.5% in 2016. This single piece of data should make people consider the level of distortion brought about by the monetary interventionism of QE. Unfortunately, as everyone knows, all chickens come home to roost.

The trend in the 10-Year US Treasury yields during the last 18 months can be attributed in large part to the Fed’s balance sheet reductions (by not reinvesting proceeds from maturing bonds) and continued upward revisions in inflation expectations from strong economic data.

The 10-Year yield has moved from 1.5% during the mid-2016 to the verge of 3% in the first quarter of 2018.

Beginning in 2008, the Fed’s fund rate was also reduced to a historically low, 0.25%. This is the interest rate at which depository institutions (banks and credit unions) lend reserve balances to other depository institutions overnight on an uncollateralized basis. The Fed funds rate more or less directly influences all other interest rates in the market: from the rates on corporate bonds (LIBOR + spread) to the rates on mortgages. This type of monetary interventionism aims to facilitate easier access and cheaper credit for both consumers and private/public institutions in order to spark economic momentum in the short term. Paired against the 10-Year US Treasury yield, it is evident as seen with the S&P 500 that artificially cheap borrowing has sparked a torrid and nearly decade-long bull run in equity markets. But at what cost?

Consequences of monetary interventionism

The Fed had artificially reduced the cost of capital to historical lows, permitting incredibly easy borrowing to both individuals and institutions.

For example:

- Auto loans increased from USD 700 billion outstanding in 2010 to USD 1.2 trillion outstanding at the end of 2017;

- Student loans in the same period moved from USD 600 billion to USD 1.5 trillion.

- US corporate debt has eclipsed USD 9 trillion (45% of GDP) and several sectors of the US economy have indulged significantly in cheap credit.

These points are to illustrate why outstanding corporate debt nowadays is at potentially at unsustainable levels.

What businesses stand the most to lose when this distorted credit cycle eventually turns and who will ultimately bear responsibility for this debt when the chickens come home to roost? We can at least provide you with direction for the first half of that question and a foundational trade thesis.

The Brewing Short

The strategy is very simple: at the next economic downturn, most leveraged companies will have financial difficulties to access credit. Some of these might eventually go bankrupt when they are unable to service their debt. We propose to short them at that time.

There are many businesses in the US who are both highly reliant on the credit cycle and are now accompanied by unsustainable levels of debt. Consumer discretionary is a particular sector within the broader economy that is especially sensitive to the credit cycle. Historically, businesses in cyclical sectors such as consumer discretionary experience high profits in periods of economic and credit expansion, which then dry up quickly when the credit cycle turns. Automobile, housing, construction, and entertainment businesses focus especially on cleaning up their balance sheets when credit tightens and wait out the downturn if they can. Although QE on this scale of implementation is unprecedented and we know little about its long-term implications on traditional market economies, we do know that many cyclical companies have participated in an all-out binge on these historically low interest rates and that these rates are once again rising fast making cheap debt increasingly more difficult to service.

A quick test to approximate the debt levels of a company are by comparing its Total Debt/Net EBITDA ratio to that of its sector benchmark and to comparable companies. If the company’s Total Debt/Net EBITDA ratio is significantly above both comparisons, this is a potential “credit zombie” and worthy of further analysis.

There are dozens of cyclical companies that are highly leveraged with these characteristics.

In this article we focus on Carmax and General Motors.

CarMax (KMX)

CarMax is a big player in the secondary automobile market in the United States who made roughly USD 16 billion in revenues in FY2017, buying used cars from both consumers and institutional dealers to then resell at a markup. KMX also offers auto financing to its customers, and this is where the business becomes very intriguing.

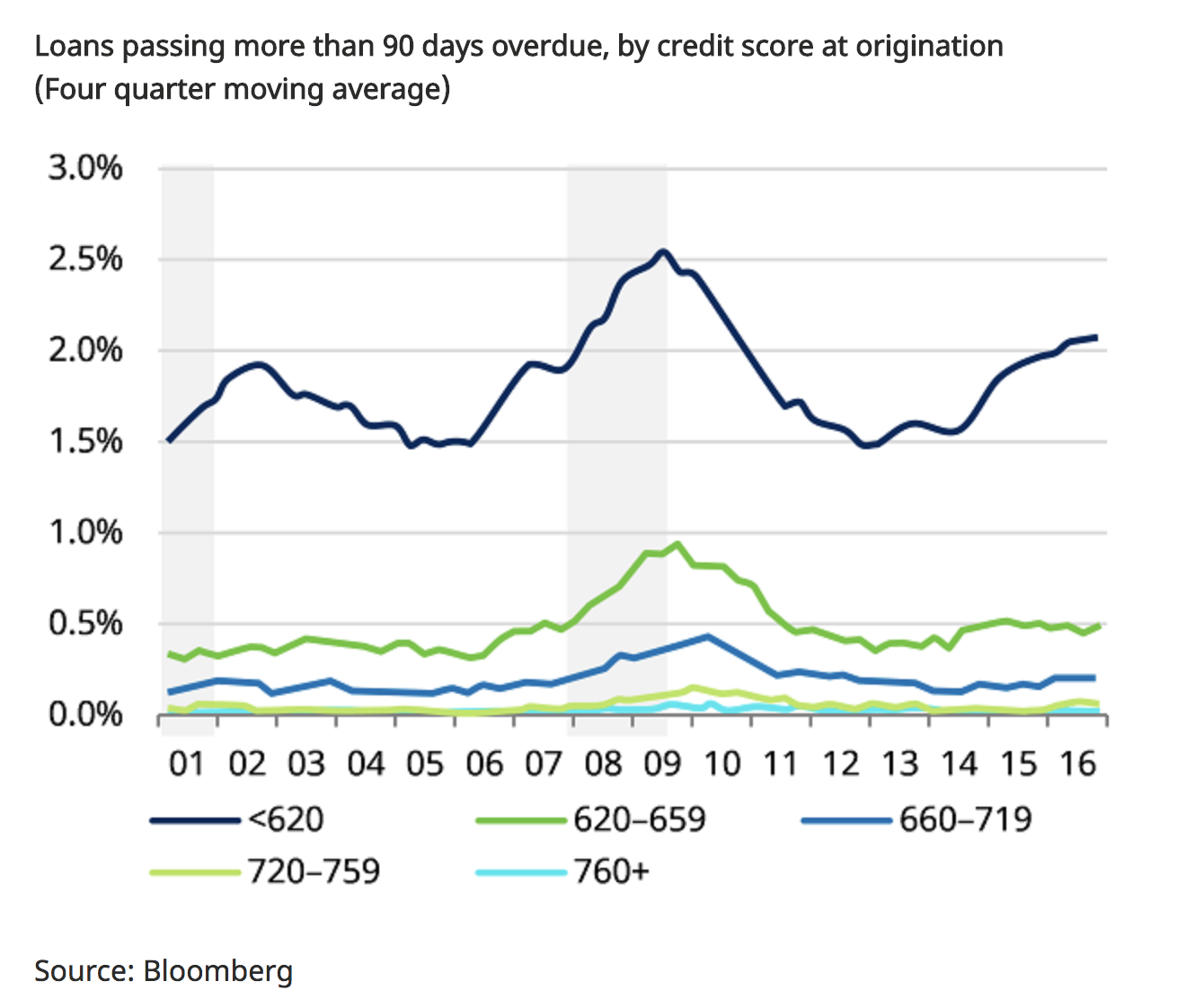

Subprime auto loans are reaching levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis. Whereas subprime auto loans, at USD 270 billion, are only a 25% portion of total auto lending, they do pose a unique risk to non-bank financial entities (NBFs). NBFs with small, highly leveraged balance sheets lending to lower quality borrowers, such as Carmax (KMX) are notable short candidates.

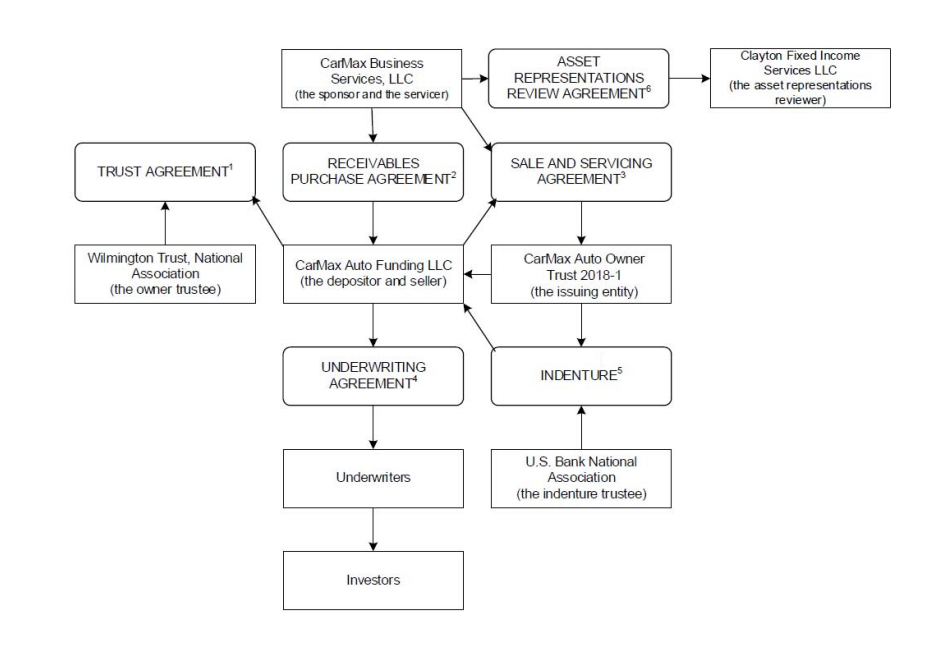

Oftentimes, when the scheme of a business operation is incredibly complicated and opaque, the business might be considered dangerous in terms of investment. Carmax is a legal labyrinth.

For every 10 cars purchased at CarMax, about 8 are financed initially through the Delaware-registered entity, CarMax Business Services LLC. These loans produced are then sold to CarMax Auto Funding LLC and pooled in another legal entity, the asset-backed “CarMax Auto Owner Trust”. The trust in exchange “sells” the notes and certificates back to CarMax Auto Funding LLC who then issues the notes and certificates of the trust to investors. Proceeds generated are then used to repay CarMax Business Services for the original transaction. A diagram of the full transaction is below:

(Transaction Overview of the CarMax Auto Owner Trust Securitization Program)

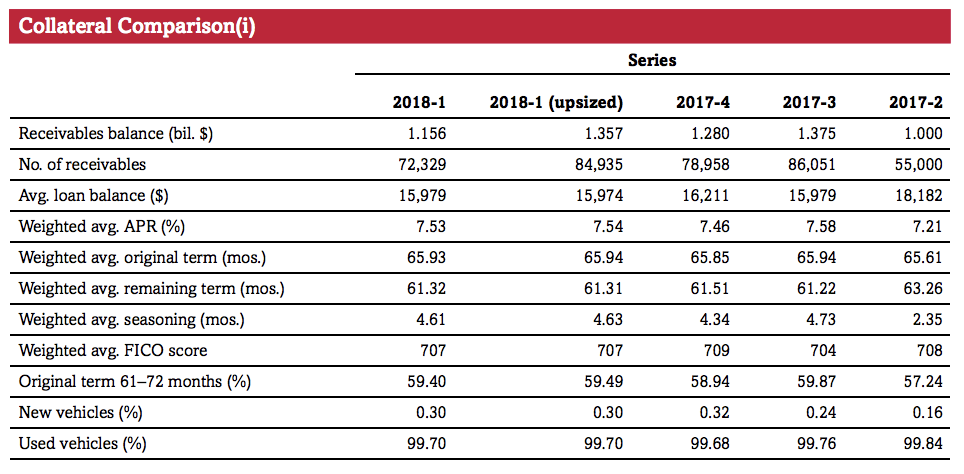

As of February 2018, CarMax has participated in over $44.0bn of auto loan ABS issuances of which about USD 11.3 billion is still outstanding debt. Note that auto loan ABS should be treated significantly different from mortgage backed securities (MBS). Used car prices often indicate the salvageable value of an auto loans collateral, and a car certainly does not hold its value over time as well as a home (MBS collateral). Thus, the value at risk as a percentage of the total original credit line for one auto loan is potentially much higher than that of a mortgage. As of the beginning of 2018, 99.70% of CarMax’s loan collateral are used vehicles with an average loan balance of ~ USD 16 thousand and a weighted average APR of 7.53% (see chart below). For reference, Bank of America currently offers a fixed-rate 5-year auto loan for used cars at 3.19% APR to borrowers with strong credit.

Source: S&P Global Ratings, CarMax Auto Owner Trust 2018-1 Report

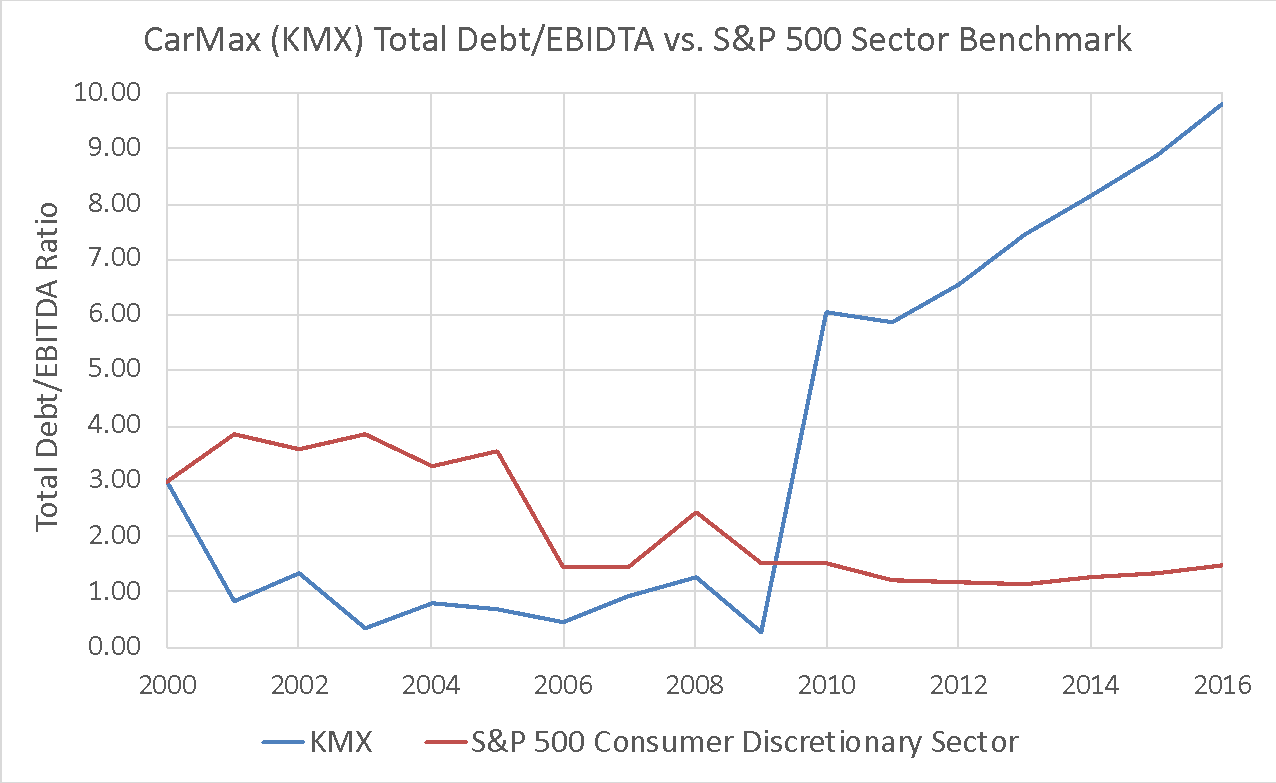

KMX’s share price has surged from roughly $30 at the end of FY2012 through nearly $62 as of 2018Q1, on the back of very strong double-digit revenue growth in 2014 and 2015. However total debt has grown 107% in that time which raises some red flags. Upon closer examination of its Total Debt/EBITDA ratio relative to the average Total Debt/EBITDA ratio of its consumer discretionary sector benchmark, the story does not look so good.

Source: Bloomberg

After keeping below the average of its consumer discretionary peers, KMX saw a severe increase in its Total Debt/EBIDTA ratio in 2010 from below 0.5 to 6.06. KMX has continued its deviation from the sector benchmark, while the sector average has stagnated around 1.25 and 1.50 since.

In 2009, KMX financed and opened 11 used car superstores, including superstores in 5 new markets. It is likely that in the depths of the recession many consumers turned to used cars as opposed to buying brand new from US automakers. KMX’s rapid store expansion and increased preference for used cars relative to new ones, likely led to its twenty-three-fold increase in Total Debt/EBITDA from 2009 to 2010 as CarMax signed off on a flood of new auto loans. From 2009 to 2010, CarMax’s total debt increased from USD 150 million to USD 4.4 billion. As of March 2018, the total debt figure is now USD 13.0 billion.

CarMax may very well be in over its head in terms of the debt that it is able to service, especially as the current credit cycle begins to cool in an environment of rising rates and tighter borrowing requirements.

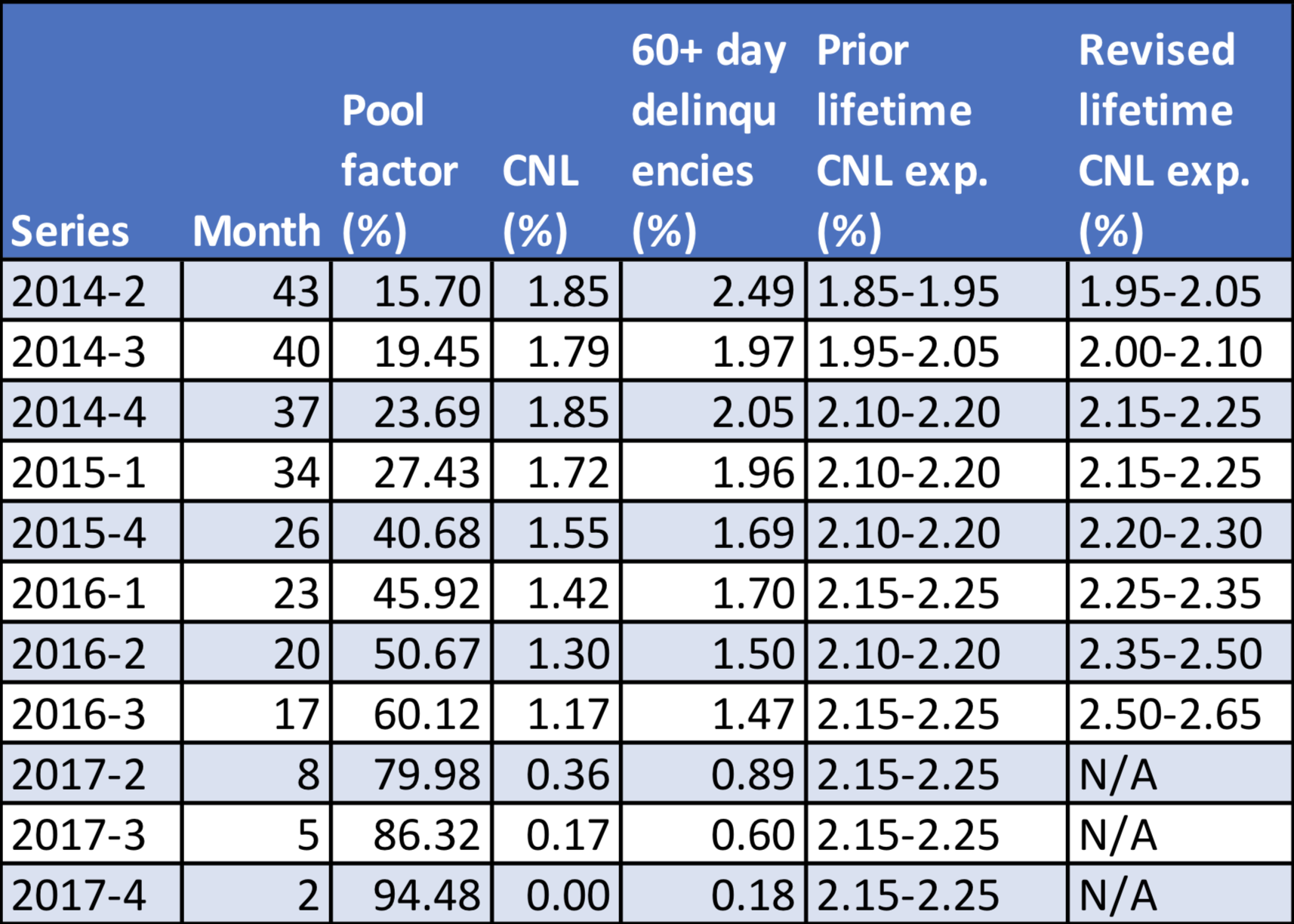

CarMax released a statement this past January providing an update on the securitization performance of its CarMax Auto Owner Trust: “CarMax’s securitization performance improved following the recession, but now, similar to other issuers, its more recent vintages are exhibiting slightly higher [cumulative net] losses (CNLs). These older pools had lower weighted average FICO scores (672-684), weaker distributions according to the issuer’s credit grade, and weathered a sharp rise in the national employment rate.” When you start out with anecdotal positive news to lessen the blow of subsequent and material negative news, not to mention diverting negative attention amongst your peer group of “other issuers”, investors reading between the lines of the corporate boilerplate will not be encouraged. In addition, every single one of the eleven CarMax ABS issuances since the beginning of 2014 received an upward revision for their cumulative net losses at the beginning of 2018. Thus, there is a strong argument that this is a macro issue and not simply a one-off issuance problem caused by a poorly distributed loan batch. This could be the beginnings of a much larger fire, egged on by tightening credit.

General Motors (GM)

General Motors is an automaker which operates worldwide. During the Global Financial Crisis it accumulated billions of losses due to a tremendous cost structure. The US government intervened to save GM from bankruptcy in the end.

Since 2011 GM has always reported a positive balance sheet but its financial debt has increased drastically. Indeed it increased from USD 10 billion in 2010 to USD 94 billion in 2017 (nowadays the amount of debt is divided into 27 billions of short term debt and 67 billions of long term debt.)

On the other hand the EBIT increased from 7.7B in 2013 to 12.4B in 2017. To make a comparison, between 2013 and 2017 the financial debt increased around 375% percent while the ebit around 61%.

This data argues that GM is a company that has binges on debt to stay competitive in the market and has exploited the debt capital markets heavily this decade without the traditional cost of borrowing.

In addition, GM warned about their high fixed costs in their most recent annual report: “Our high proportion of fixed costs, both due to our significant investment in property, plant and equipment as well as other requirements of our collective bargaining agreements, which limit our flexibility to adjust personnel costs to changes in demands for our products, may further exacerbate the risks associated with incorrectly assessing demand for our vehicles.”

Furthermore, GM sells more than 45% of their cars in China. This present two risks:

The real risk is that China has a private debt to GDP of over 200%, which makes the country largely exposed to a possible financial crisis.

A possible trade war escalating between USA and China could impact GM business in China (tail-risk).

Timing

The most important aspect of any short thesis is the timing. Admittedly, to have the foresight to predict the exact timing of a downturn is almost impossible and a mug’s game for most who attempt the feat.

The best advice, given by Ray Dalio, is to compare wage growth with the increase on the interest rates of consumer/retail debt.

In a highly leveraged economic environment this comparison might best hint at a market top.

When interest rates for the average man increase at a faster rate than wages, the ability to repay debt becomes progressively more difficult. Consumers borrow less, buy less, and may face bankruptcy upon default. Ultimately, mass consumer default permeates into the corporate world, and in the past, not even institutional lenders have escaped unscathed from credit downturns.

0 Comments