The Telco Business

The importance of the telecom industry has been brought to light in recent months as the global pandemic forced millions to work from home resulting in huge increases in reliance on mobile phone networks and broadband.

The telecommunication sector, as a whole, can be broken down into several different businesses, that are sometimes bundled together because of potential synergies, but that fundamentally can be run separately. Indeed, the largest telco players bundle together cable and broadband services with mobile network services and oftentimes they have a media branch that comes along. It is important, in order to understand how this came to be, to look at some history.

Originally in Europe, the incumbents were state monopolies that owned the fixed-line cable infrastructure and that were commissioned by their respective governments to develop the mobile infrastructure as the technology was developed. Over the 1990s these incumbents started to be privatized and in 1998 Europe obliged all the players to follow some common standards for interoperability of the mobile network and obliged the incumbents to allow competitors to provide mobile services at an agreed wholesale price.

The result was an industry composed by players with different levels of vertical integration. The incumbents, such as BT(British Telecom), Telecom Italia, Deutsche Telecom, Telefónica, Swisscom or Orange (France), which (used to) have the majority cable infrastructure and use it to provide fixed-line phone, cable and broadband services; in addition to that, they own a big portion of underlying mobile network infrastructure and use it to provide mobile and internet services. Then there are broadband service providers that rent the cable infrastructure and can either offer just internet services, or also bundle the cable tv and media channels, such as Sky, Virgin Media (Liberty Global Group) or the Dutch Ziggo. Then there are the Mobile Network Operators which own a portion of the tower infrastructure to provide mobile services and here we see Vodafone or Iliad. In this category are included the majority of large players in the mobile industry because most of them own at least a percentage of the network they use because it was deemed strategic, but, as we will see, the times are changing. Finally, there is an incredibly high number of so-called Mobile Network Virtual Operators that just rent the network from specialized “TowerCos” and basically compete by offering better services or lower prices leveraging on the nimble cost structure.

Connectivity has been commoditized as consumers now view Internet connectivity as a basic utility – like water or electricity. This has resulted in tough pricing conditions. Pricing power comes from network speed, reliability, top bandwidth, near-real-time latency and security. Operators are therefore forced to maintain high network investments in order to satisfy the ever-increasing demand for data. As a result, companies may be forced to raise prices but consumers may be unwilling to pay a huge premium no matter how fast the network.

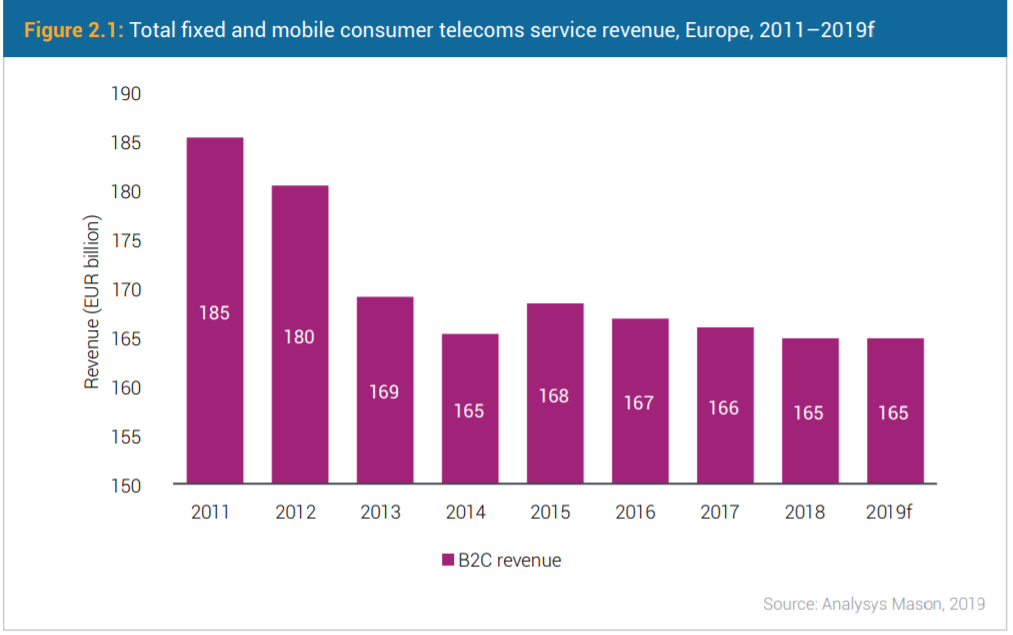

Indeed, in Europe the fragmented competitive landscape has hit the pricing power of Internet Service Providers, driving it down to almost zero. As the next figure shows, the telco revenues to consumers have been drastically reduced over the past decade.

In the fixed-line business, the revenues have been going down by the downfall of fixed-phone revenues that have fallen out of fashion in the new generations and that used to represent 35% of revenues at the beginning of the decade (now just over 20% and with a CAGR of negative 7%). In the mobile business, the revenues have been driven down by the excessive presence of MNVO. Indeed, in Europe there is an incredible amount of Service providers in proportion to the population as the next exhibit shows (data as of 2019, by Delta Partners).

Source: Analysis Mason, 2019

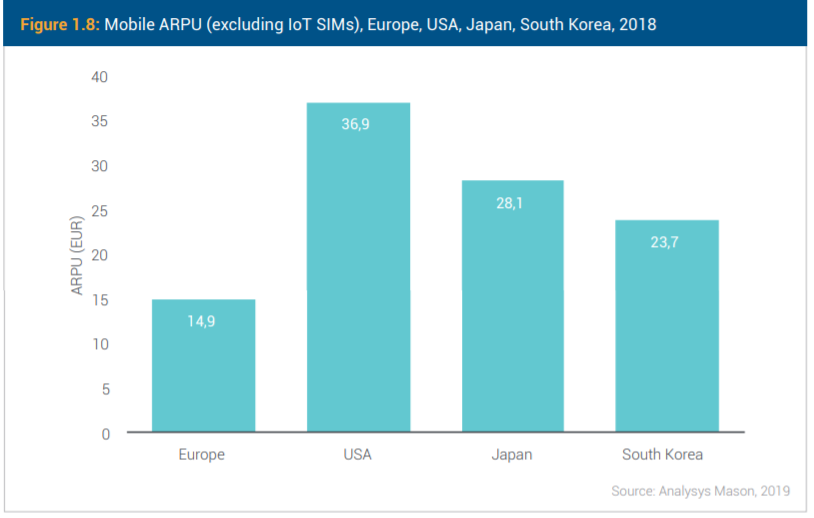

This excessive competition drove down prices disproportionately and, as we can see from the following exhibit, the Average Revenues Per User difference with respect to other developed countries is staggering.

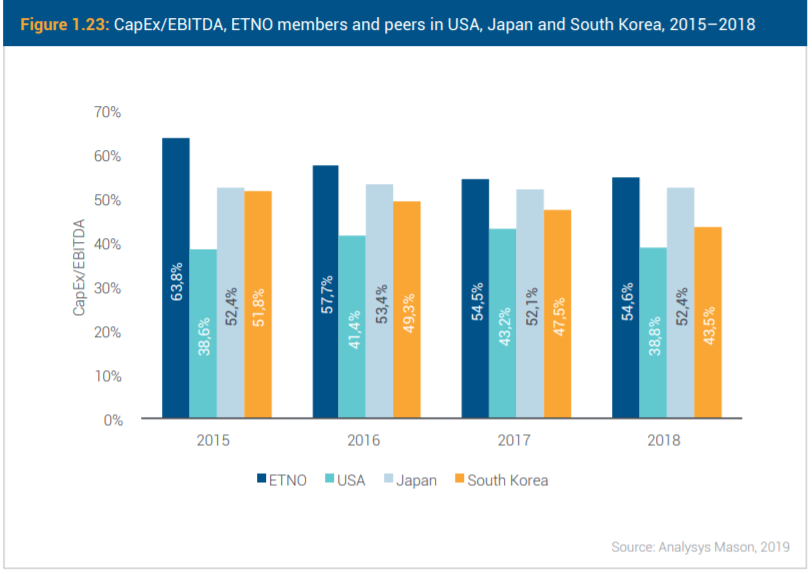

Furthermore, another key difference is the excessive capex that weighs in as a higher percentage of costs and severely impacts profitability. Indeed, as the next figure shows, the capex/EBITDA in Europe used to be much higher than its peers, due to overlapping in the infrastructure, but now, thanks to the dynamic we’ll explore in theme 2, the difference has significantly dropped.

Source: Analysis Mason, 2019

Source: Analysis Mason, 2019

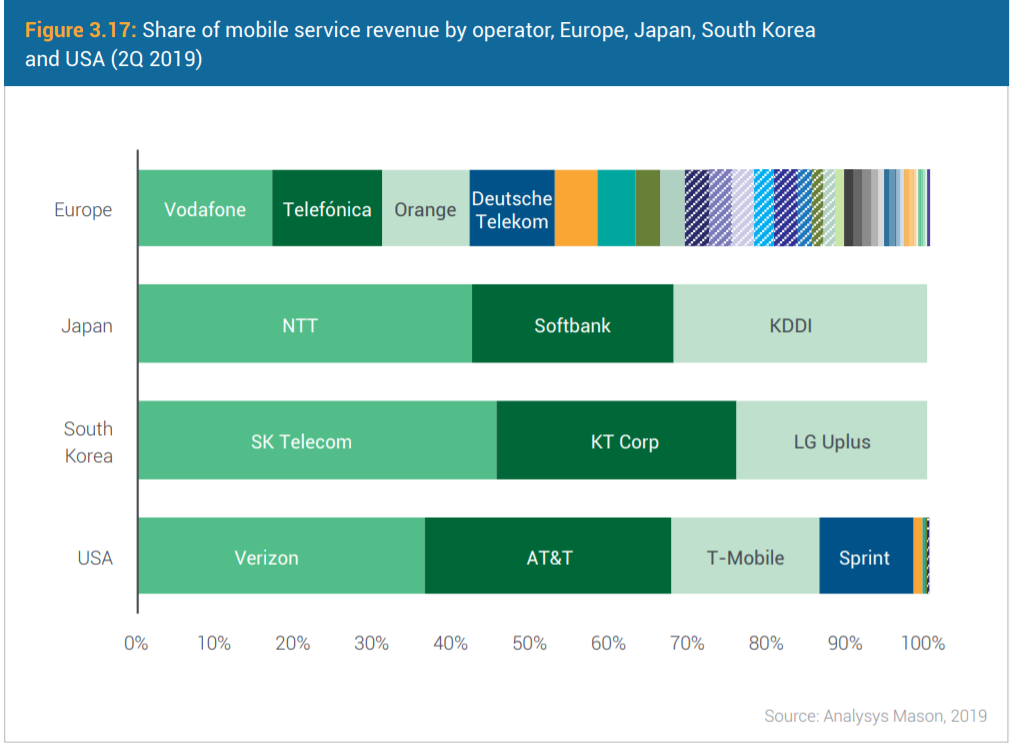

A crowded market and lack of cross border M&A

As previously mentioned, what makes the European telecom market so unique is its extreme fragmentation. For reference, the U.S., with a population of 330 million, has three major telcos. China, with a population of 1.4 billion, also only has three major telcos. The EU, with a population of 450 million, has around 40 major telcos as the next figures show:

Source: Analysis Mason, 2019

Such a crowded market, coupled with the commodity-like nature of product offerings, has locked the European telecom market in a perpetual price war. This price competition has made the European telecom industry one of the most deflationary in the world, with the price per gigabit of data decreasing 33% YoY. This has also caused the combined market cap of the European telecom sector to crash 75% in the two decades since the year 2000. This begs the question: why has there not been industry consolidation?

The answer lies in the hawkish stance of the European Commission in regards to telecom M&A. Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s competition commissioner, has been especially active in blocking telecom M&A proposals on consumer interest grounds. The de facto rule has been that each country’s telecom market needs to have 4 major players, and any M&A that reduces that number will not be approved. Examples include the failed merger between Telia and Telenor in Denmark in 2015, and the blocked merger between Telefonica’s O2 network in the UK and CK Hutchison’s Three in 2016. Even when regulators have approved telecom M&A, they have often required companies to make a number of concessions in order for markets to maintain the same level of competition. For example, in 2016 regulators approved the €21bn merger of Three with its rival Wind in Italy. However, a precondition of the deal was that Iliad, a telco from France, would enter the Italian market and the merged entity would sell a significant portion of their assets to Iliad. This effectively undermined any benefits of the transaction as Italy remained a market with 4 telcos and the price competition from Iliad, an entrant looking to aggressively gain consumers, was actually a net negative for the rest of the market. In fact, the combined entity of Wind and Three lost 8.5 million subscribers in the past three years and its revenues decreased 25% in the same period.

Nonetheless, one recent development in the industry has the potential to catalyze a wave of consolidation. In May of this year, the General Court, the EU’s second-highest court, annulled a 2016 decision by the European Commission to block the £10.25bn takeover of Telefonica’s O2 network in the UK by Three. This has been a significant blow to the powers of EU Commission, especially in terms of their ability to block mergers that decrease the number of telcos in a market from four to three. The EU Commission itself seems to also be overhauling its outlook towards telecom M&A. Margrethe Vestager, previously one of the biggest opponents of industry consolidation, has recently indicated that she would like to see more cross-border M&A within Europe to create pan-European telco champions. Her change in tone was motivated in part by the steep decreases in market values for European telcos due to the coronavirus, which left many companies vulnerable to opportunistic bids from Chinese or American buyers. It should also be noted that the EU’s new Commissioner for Internal Market is Thierry Breton. Thierry Breton was formerly the CEO of France Télécom and is expected to be much more accommodating to M&A proposals from the industry. All these factors have the potential to galvanize a wave of consolidation in the industry, especially in countries where you currently have 4 or more players. This includes countries like Italy, France, Spain, Sweden, and Denmark.

A primer on the wireless business

Before looking at the alternatives to consolidation that telecom companies have, in the following section we will focus more in depth on how the wireless infrastructure works, to understand how improvements could be made. As anticipated above the infrastructure of broadband and mobile services are substantially different, hence telco companies have traditionally run them separate businesses and only in the past decade the convergence by bundling the services together has taken some traction.

Wireless infrastructure

Over the last couple of decades, tower ownership has increasingly been transferred from MNOs to separate tower companies (TowerCos). These TowerCos can take the form of an internal division within an MNO, a separate entity controlled by an MNO or a wholly independent entity. But how exactly does the infrastructure work?

The towers are composed by a passive component that is the mast itself and the related infrastructure such as the power equipment and surrounding facility, and an active component installed by each MNO that must be then updated according to the level of service it can provide (3G, 4G and in the future 5G). On each tower, if accordingly modified, there can be installed multiple active components that service multiple MNOs avoiding redundancy. It is important to notice that the tower then latches onto the cable infrastructure and here some other synergies may be found, but still the wholesale price for accessing the fiber network is set, so the advantage is not substantial. An important metric is the Co-location ratio that expresses how many MNOs can use the same infrastructure. In the figure the tower would have a ratio of 2:1.

To give an idea of the size of the infrastructure investment, according to data reported by Statista, in 2018 there were 421,000 tower sites in Europe, with the annual growth in tower sites estimated to be about 1-3%. The following figure shows the distribution in the largest markets that account for 60% of the European market.

1000s of tower sites in selected European Geographies.

Sale of infrastructure assets

The peculiarities of the European Telecom market mentioned above have caused telecom companies in Europe to look for “back door” routes to consolidation. With about 40 network operators across Europe and a lack of M&A due to antitrust concerns, the pooling of towers is expected to achieve similar cost and scale benefit as consolidation without concerns over consumer harm. In recent years, several telecom companies such as Bouygues as well as Sunrise and Iliad have decided to cash in and sell their towers to specialist companies such as Cellnex or Blackstone’s Phoenix Towers. The pace of these deals is likely to accelerate in the future as tower specialist enjoy high valuations and network operators need to raise cash for investments: for example in July Cellnex raised € 4bn to pursue more acquisitions to be ready for this new wave. Alternatively, in the best of the situation, telecom companies can construct deals that allow them to retain control of the infrastructure asset while maximizing financial gain. An example of this approach would be Inwit, a joint venture between Vodafone and Telecom Italia operating their Italian merged tower business, and Vantage Towers, Vodafone’s German mast business, which will list on the Frankfurt’s Deutsche Borse at the beginning of 2021 and also Altice in France, which sold 49.99% of its tower business to maximize the financial gains while still keeping control. The sale of infrastructure assets allows telecom companies to unlock higher valuations for the TowerCos and FiberCos, with deal multiples 10 valuation points higher than mobile and convergent operators’ multiples, to raise the cash needed for investments and to move debt off the balance sheet of the parent company.

Source: Bain Analysis; data: CapitalIQ, Morgan Stanley, Mergermarket

On the other side, private equity infrastructure funds, government funds and pension funds are attracted by the cash flows of these assets and see a large growth opportunity in connectivity. The GSMA expects the global operator revenues and investments to jump by $ 110bn to $ 1.14tr between 2018 and 2025. Telecom towers as well as fibre networks are an opportunity to obtain access to predictable cash flow coming from the rental payments. While these assets require significant upfront and maintenance investments, they could generate increasing revenues as telecoms deploy new antennas and equipment to build 5G networks.

As a case in point, a recent deal involving the sale of infrastructure assets is the sale to KKR of 37.5% of FiberCop, a new company owning Telecom Italia’s so-called last-mile network., for € 1.8bn. The deal valued the NewCo at € 7.7bn of enterprise value (for an equity value of € 4.7bn) and Telecom Italia will still detain the majority of the company with a 58% stake while the remaining 4.5% is detained by Fastweb, thanks to its 20% stake in the joint venture FlashFiber, now part of FiberCop. The NewCo will leverage the existing fibre network of FlashFiber and will use the help of KKR to upgrade the copper part of the remaining network to fibre. In addition, the fibre network will be realized based on a model of co-investment open to all the other Italian operators; in this direction Telecom Italia already signed a memorandum of understanding for a strategic partnership with Tiscali, to be realized through Tiscali’s economic participation in FiberCop. According to the business plan, FiberCop will have an EBITDA of € 900M and will be EBITDA-CAPEX positive starting from 2025 and it won’t require any further injection of capital from the shareholders.

1 Comment

The Banker’s Toolkit n.1 – a Guide to the Telco Industry – BSIC | Bocconi Students Investment Club · 20 February 2022 at 17:33

[…] could be explained by a series of motives here listed but developed more in depth in the article “Rise of the Specialists”. First, the more experienced management, with towers as their key focus, would be improved, […]