Introduction

“I have two basic rules about winning in trading as well as in life: (1) If you don’t bet, you can’t win. (2) If you lose all your chips, you can’t bet.” Larry Hite

When it comes to speculating in the stock market, the most important element is also one of the most neglected ones by retail investors: risk management. If you manage your portfolio with your emotions and without discipline, prepare for a volatile ride, probably without anything worthwhile to compensate for your efforts in the end. In the stock market and in life, the risk is unavoidable. The best anyone can do is to manage risk through sensible planning. The only way to control risk when trading stocks is through how much we buy and sell when we buy and sell, and how we prepare for as many potential events as possible. Your goal is not risk avoidance but risk management: to mitigate risk and have a significant degree of control over the possibility and amount of loss.

It Is Never Market’s Money

When buying stocks, one should always have a clearly outlined plan on how to avoid losing all the invested money, staying true to the infamous quote often used in poker: “If you lose all your chips, you can’t bet”. Moreover, the retail investor should always be aware that the invested money is his money. This is especially important when a stock is in the profit zone because many traders regard profits as house money. Hence, they differentiate between profits and principal, leading to more reckless bets as the investor feels that the profits are the market’s money anyway. The successful investor will do his best to protect his profits and never let a profit turn into a loss.

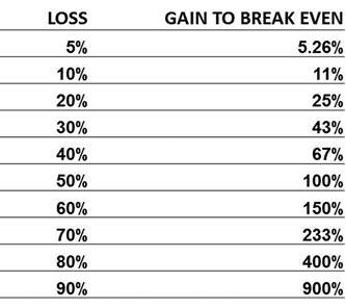

As important as having a clearly outlined plan to preserve one’s capital is having sound risk-management principles to achieve constant returns in the markets. Principles are there to help attain profits and keep you from being overconfident after a period of great success. To better understand why the latter is crucial, we would like to highlight the following table showing the percentage gain needed in a portfolio to return to break-even after incurring a loss.

Figure 1 – Gain needed to break even from loss

Source: Minervini, Mark. Think & Trade Like a Champion: The Secrets, Rules & Blunt Truths of a Stock Market Wizard

By looking at Figure 1, it is imminent to see that retail investors should never allow their portfolios to surpass a certain loss of, for example, about 10% since basic mathematics starts working against them at this point. This shows how overconfidence and carelessness (neglecting one’s risk-management principles) can quickly lead to a disaster. Moreover, once you suffer a loss, let’s say 50%, not only does this stock have to rise by 100% to reach break-even, but the investor’s account also diminishes significantly. This can turn out to be the start of a vicious cycle of gaining profits when the account is small and losing money when the account is big. To better demonstrate how losses work geometrically against speculators, let us examine Figure 2.

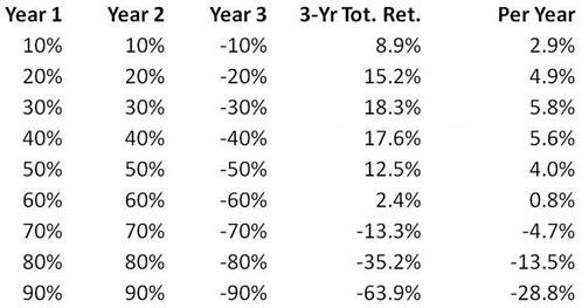

Figure 2 – Various returns based on three-year compounding

Source: Minervini, Mark. Think & Trade Like a Champion: The Secrets, Rules & Blunt Truths of a Stock Market Wizard

For example, if a trader had two up years of 50% and one down year of 50%, then the compounded three-year annual return would be 12.5%. This is equal to a return of about 4% per year, which is not desirable regarding the risk taken up by the trader. A successful speculator should always have his gains eclipse his losses on a risk/reward basis. To achieve this objective, it is crucial to close losing positions before they turn into significant losses.

Accepting the Market’s Judgments

Many retail investors do not reduce their losses effectively simply because of two reasons: exiting a position is similar to admitting that one’s judgement or the timing was wrong, and so admitting a mistake, and secondly, they usually put a lot of work and effort into analysing and researching a stock before buying it, so if the stock does not move in their favour they are resistant to “throw” all their hard work away. As a retail investor, it is of great importance to understand that the only thing one can and should control is the size of his loss since it will protect his account from a major setback. It is essential to know that every major correction begins as a minor reaction, it is impossible to tell if a 10% decline is the beginning of a 60% decline or worse.

In general, there is no such thing as a safe stock. Many “high quality” companies experienced periods of major drawdowns, which took them years to overcome. Let us take into consideration Coca-Cola, for example; after its record-high in 1973, the company’s shares went down a70% (233% to break-even), and it took them 11 years to get back to even only to decline again by 50% in 1998. This illustrates why timing and limiting losses are two crucial ingredients for success in the markets. Moreover, it suggests that retail investors should keep close track of their investments because even investment-grade companies today will certainly face new challenges which they might or might not be able to overcome. When it comes to trading and investing, an investor’s ego must take a back seat as one cannot allow himself to hold on to a losing position simply because one does not want to accept a mistake. Moreover, it is vital to follow one’s risk-management principles to never get too greedy and not sell at a profit or too hopeful and not sell when losses are piling up because, in the end, there is only one opinion that counts: the verdict of the market.

Losses Are a Function of Expected Gain

Just as an insurance company utilizes mortality tables, you can use a similar method for your trading: basing the amount of loss on the average “mortality” of your gains. To make profits consistently, you need a positive mathematical expectation for return, your maximum loss tolerance depends both on your batting average (percentage of profitable trades) and on your average profit per trade (expected gain). Let’s assume that a trader is profitable on 50% of his trades. Therefore, he must on average make at least as much as he loses to break even over time. Although going forward these numbers can only be based on assumption, it’s the average gain from your actual trades that’s the key number. After you have calculated these numbers, you will be able to get a much clearer picture of where you should be limiting your losses. In the words of Warren Buffett, “Take the probability of loss times the amount of possible loss from the probability of gain times the amount of possible gain. . . . It’s imperfect, but that’s what it’s all about.”

Over time your average gain will improve as you learn how to trade more effectively. You should monitor your average gain on a regular basis and adjust your loss tolerance accordingly. Systems that rely on a high percentage of profitable trades cannot be effective. If a trader must be right on 70% or 80% of his trades and that is his edge, what happens if he is right only 40% or 50% of the time during a difficult period? The problem with relying on a high percentage of profitable trades is that no adjustment can be made, you can’t control the number of wins and losses. What you can control is your maximum loss; you can tighten it up as your gains get squeezed during difficult periods. It is important to keep a good risk/reward ratio so that you can have a relatively low batting average and still not get into serious trouble. At a 2:1 ratio, you can be right only one-third of the time and still not get into real trouble. At a 3:1 ratio, even a 40% batting average could yield great results.

Not All Ratios Are Created Equal

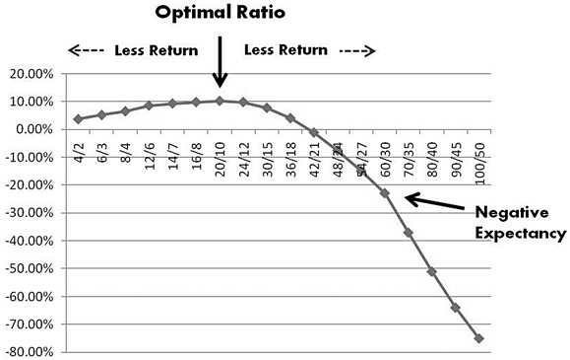

During difficult periods, your gains will be smaller than normal, and your percentage of profitable trades (your batting average) will be lower than usual, and so your losses must be shorter to compensate. It would be fair to assume that in difficult trading periods your batting average is likely to fall below 50%. Once your batting average drops below 50%, increasing your risk proportionately to compensate for a higher expected gain based on higher volatility will eventually cause you to hit negative expectancy; the more your batting average drops, the sooner negative expectancy will be achieved. As the next figure illustrates, at a 40% batting average your optimal Gain/Loss ratio is 20%/10%; at this ratio, your return on investment (ROI) over 10 trades is 10.2%. Note that the expected return rises from left to right and peaks at this ratio. Thereafter, with increasing losses in proportion to your gains, the return declines.

Figure 3 – Total compounded return per 10 trade at 40% batting average

Source: Minervini, Mark. Think & Trade Like a Champion: The Secrets, Rules & Blunt Truths of a Stock Market Wizard

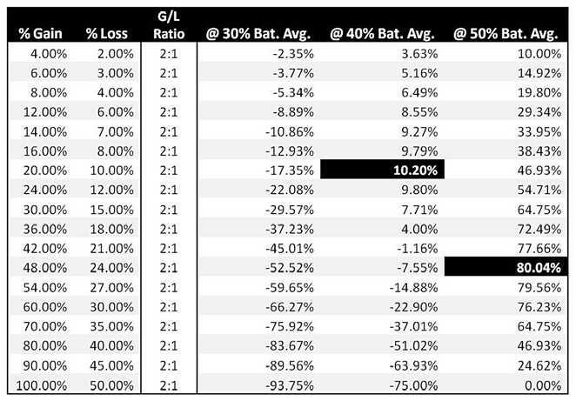

Armed with this knowledge, you can understand which ratio at a particular batting average will yield the best-expected return. This illustrates the power of finding the optimal ratio. Any less or any more and you make fewer profits. If your winning trades were to more than double from 20% to 42% and you maintained a 2:1 gain/loss ratio by cutting your losses at 21% instead of 10 %, you would lose money. This is the dangerous nature of losses; they work geometrically against you. At a 50% batting average, if you made 100 % on your winners and lost 50% on your losers, you would do nothing but break-even: you would make more gains taking profits at 4 % and limiting your losses at 2%. Not surprisingly, as your batting average drops, it gets much worse. At a 30% batting average, profiting 100 % on your winners and giving back 50% on your losers, you would have a 93% loss in just 10 trades. If you’re trading poorly and your batting average is dropping off below the 50% level, the last thing you want to do is increase the room you give your stocks on the downside. This is not an opinion; it’s a mathematical fact. Many retail investors give their losing positions more freedom to inflict average deeper losses.

Figure 4 – Total compounded return per 10 trades at various batting average

Source: Minervini, Mark. Think & Trade Like a Champion: The Secrets, Rules & Blunt Truths of a Stock Market Wizard

Keep yourself in tune with your portfolio

A losing streak usually means it’s time for an assessment. If you find yourself in losing positions over and over, there can only be two things wrong:

1. Your stock selection criteria are flawed.

2. The general market environment is hostile.

Broad losses across your portfolio after a winning record could signal an approaching correction in a bull market or the advent of a bear market. If you’re using sound criteria regarding fundamentals and timing, your stock picks should work for you, but if the market is entering a correction or a bear market, even good selection criteria can show poor results. It’s not time to buy. If you’re experiencing a heavy number of losses in a strong market, maybe your timing is off. Perhaps your stock-selection criteria are missing a key factor. If you experience an abnormal losing streak, first scale down your exposure. Don’t try to trade larger to recoup your losses fast; that can lead to much bigger losses. Instead, cut down your position sizes; for example, if you normally trade 5,000-share lots, trade 2,000 shares. If you continue to have trouble, cut back again, maybe to 1,000 shares. If it continues, cut back again. When your trading plan is working well, do the opposite and pyramid back up. When you take a large loss or you are in a losing streak, there is a tendency to get angry and try to get it back quickly by trading larger. This is a major mistake many traders make and is the opposite of what should be done. Trade smaller, not bigger. If you keep trading the same size over and over, even making small mistakes can lead to a “death by a thousand cuts”. Instead, scale back your trading size and raise the cash position in your portfolio. Stock trading is not an on-off business; moving from cash into equities should be incremental. You should start with “pilot buys” by initiating smaller positions than normal; if they work out, larger positions should be added to the portfolio soon thereafter. This simple approach helps keep you out of trouble and build on your successes. If you’re not profitable at 25% or 50% invested, why move to 75% or 100% invested or use margin?

There’s no intelligent reason to increase your trading size if your positions are showing losses. pyramiding up when you’re trading well and tapering off when you’re trading poorly, you trade your largest when trading your best and trade your smallest when trading your worst. Be incremental in your decision-making process. Build on success. Subtract on setbacks. Let your portfolio guide you.

0 Comments