Introduction

On October 8th, 2020, Morgan Stanley announced its acquisition of Eaton Vance Corp., a publicly listed, Boston-based asset manager with over $500bn in AUM. The firm will acquire all the shares of Eaton Vance on a 50% cash-50% stock basis. Based on Morgan Stanley’s share price on October 7th, 2020, the transaction is valued at USD $6.5bn. This represents a 38.4% premium on the previous day closing price of Eaton Vance.

Such a transaction marks a continuation of two major trends that have been driving M&A in the asset management space for the past few years. Firstly, most major investment banks, in search for stable fee based revenues and high margins, are quickly growing their asset management divisions. This has led to many investment banks acquiring complementary asset management platforms to build out their product offerings and distribution networks. The asset management industry as a whole is also engaging in defensive consolidation. As fees are compressed across the industry, due to the increase in reporting requirements and the shift from active products to low-cost passive offerings, firms are looking to merge with competitors and cut their cost bases. In addition, as more LPs look for one-stop-shops to satisfy the entirety of their asset allocation requirements, asset managers have been given even more of an incentive to acquire targets that help them build a complete product suite.

Industry Overview

Business Models:

1.Product Providers

This is the role that is traditionally occupied by asset managers, which provide various products (e.g. mutual funds, exchange traded funds, money market funds, multi-asset funds, retirement plans) in order to grant clients access to a wide range of asset classes, including equity, fixed income, commodities, forex, and alternatives.

2. Solutions Providers

Some asset managers have tried to expand their offering by also providing solutions, such as the outsourced chief investment officer (OCIO), namely a professional who is contracted to manage a company’s investment strategy on an as-needed basis. Yet the required skills are very different, and few have figured out how to perform both roles effectively.

3. Platform Providers

Many asset managers operate in-house distribution and fund administration platforms, typically from their back office. With the recent growth of independent platforms and the associated interest of private equity firms in this business, managers will be forced to make strategic choices – open up to third parties or sell to private equity firms or to a competitor acting as a consolidator.

4. Infrastructure/Data Providers

A growing number of asset managers are looking to replicate the success of those that offer in-house infrastructure and data collection to third parties. Again, however, the skill set to succeed is markedly different from managers’ traditional core competencies.

5. Capital Providers

Finally, asset managers can act to bridge customers’ cash flow needs. Guaranteed outcomes, even if they come at the expense of capping upside, are in demand, particularly in the affluent and mass market. This creates a role as capital providers beyond the traditional offering of life insurance products.

Industry Growth:

Sources: BCG GAM Database 2020

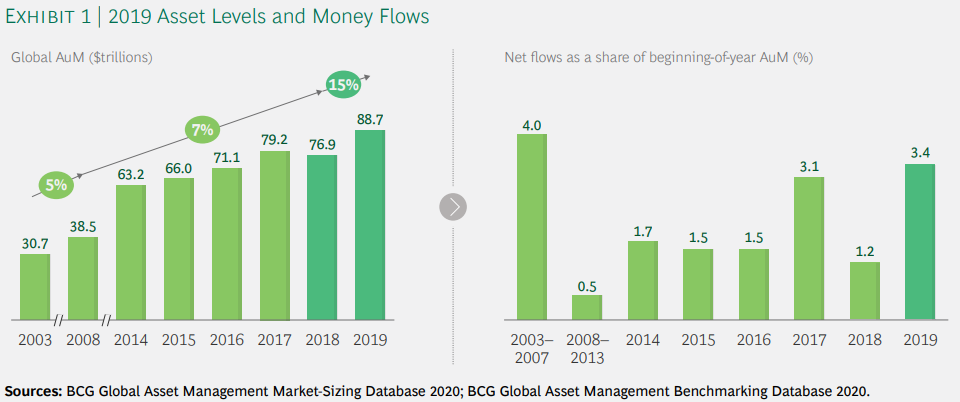

Following an AUM decline of $2tn in 2018, asset managers made a significant comeback in 2019. Total AUM in nearly every region grew by a double-digit percentage, thanks to strong market performance and net flow figures. The total value of global AUM grew by 15% in 2019 to about $89tn, up from about $77tn in 2018.

Retail clients, representing 42% of the global assets at $37tn, grew even faster, at 19% in 2019, while institutional clients, representing 58% of the market grew by 13% to $52tn. Market performance was the primary driver of this growth, contributing roughly ¾ of the AuM growth in 2019 as markets across regions posted record highs for the period since the 2008–2009 financial crisis, as the longest bull market in history.

Geographical Breakdown:

Sources: BCG GAM Database 2020, BCG Analysis, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Strategic Insight, and others

1.North America

North America is the world’s largest asset management region by AUM, and it also experienced the strongest growth. Much of the AuM expansion is attributable to quantitative easing, strong consumer spending, and a historically low unemployment rate.

2. Europe

Europe, the second largest region by assets, realized strong AuM growth. The institutional segment was a major driver of the region’s growth.

3. Asia-Pacific

The most developed markets here are Japan and Australia. Both markets benefited materially from the year’s strong market performance. The region’s growth was heavily influenced by China, whose asset management industry is tilted toward retail investors.

4. Latin America

Heavy investment in fixed income and strong market results in this asset class helped fuel the region’s growth. Most of the increase came more from retail portfolios than the institutional sector. Notable growth occurred in pension funds, as more employers provide retirement plans and as employee contributions to these plans gradually rise.

5. Middle East and Africa

The region’s growth was driven by strong market performance and higher oil prices during 2019.

Asset Growth Breakdown:

Sources: BCG GAM Database 2020, Strategic Insight, ICI, P&I, HFR, Blackrock, INREV, BCG Analysis

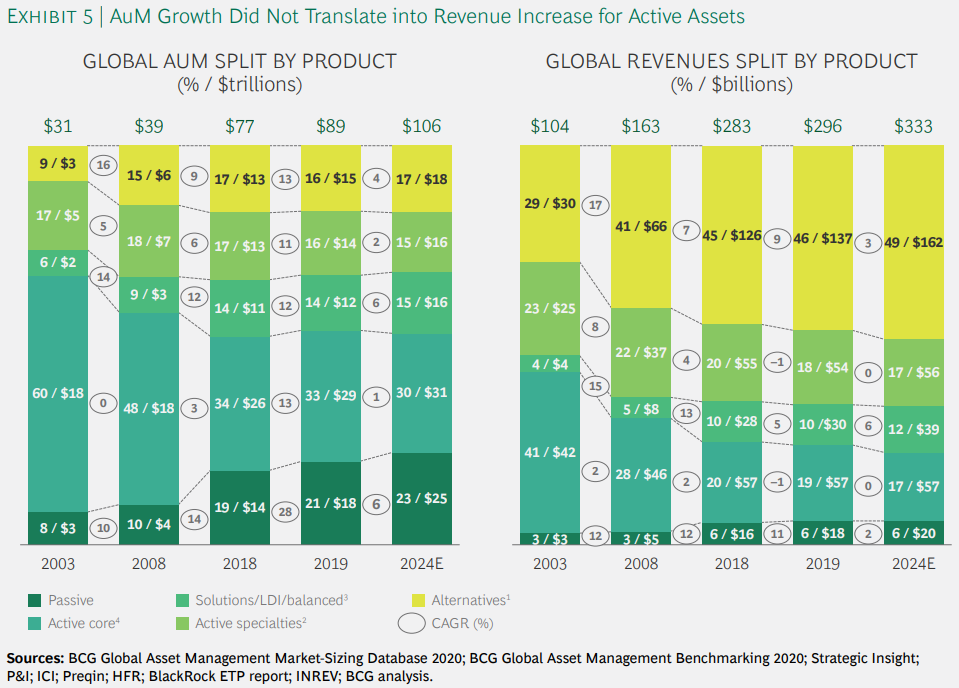

1.Alternative products

They captured AuM growth of 13% for the year. This asset class has grown from less than 10% of the total market AuM in 2003 to 16% in 2019. It has become the largest revenue pool across products.

2. Active products

They continued to lose out to other categories in 2019. Their market share of global assets has fallen by nearly half since 2003, from 60% to 33%, while their share of global revenues has dropped dramatically, from 41% in 2003 to less than 20% by 2019.

3. Passive products

They overall grew faster than any other product category, with total AuM rising by 28% in 2019. Equity and fixed income exchange-traded funds (ETFs) produced the highest AuM growth rate in passive products, at 32% and 35%, respectively.

4. Solutions products

Their growth seems to have plateaued. Still, growth in these products should increase in the years ahead, given higher interest in products such as outsourced chief investment officer (OCIO) and liability-driven investment (LDI) as institutional investors demand more customized services.

5. Sustainable products

Sustainable investing has experienced a dramatic rise in prominence in asset management, driven by the increasing financial relevance of ESG factors, better ESG data, growing investor demand, and growing regulatory pressure. Since 2012, global assets managed by one or more sustainable investing methodologies have grown by 15%.

Consolidation within the overall industry

M&A activity within the Asset Management industry was relatively cyclical between 2009 to 2017, with no clear trend. That all changed in 2018, when M&A in the sector hit the all-time high with 253 transactions announced and deal value rising 29% from 2017 to $27.1bn. 2019 was another record number of transactions announced, a second consecutive year in a row. Furthermore, despite the coronavirus pandemic crisis shaking the markets, deals within the industry in 2020 have grown even larger. The value of mergers and acquisitions in the wealth and asset management industries climbed to a combined $19.7bn in the first six months of 2020 which is a 47% increase from the first six months of 2019, according to a report from PWC. The forecasts for the rest of the year expect the number of transactions to continue at pace.

Source: PwC Global AWM Research Centre Analysis, Lipper, Morningstar

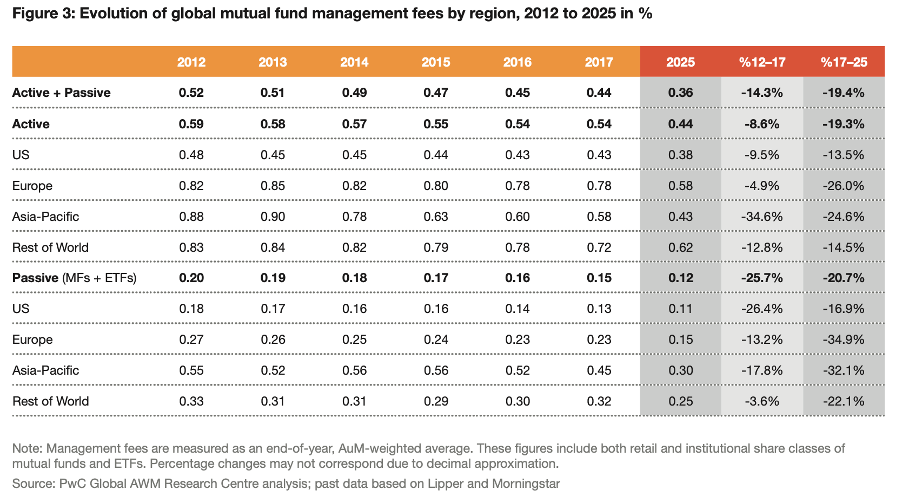

One of the primary reasons causing this wave of M&A is the fee compression across the industry. As seen by the table above, fee levels across the board have decreased significantly over the past few years, with the overall industry seeing an average decrease of 14.3% in fees between 2012 and 2017. Fee levels are further expected to decrease by 19.4% by 2025.

A primary reason for this pressure on fees, especially for active funds, is the increasing shift to passive low-cost offerings. This shift began in 2008, as investors grew wary of the volatile returns and high fees of active managers. Eventually, in August 2019, assets in passive US equity funds overtook those in active equity funds for the first time. Active firms like securities, Invesco, Franklin Templeton, Pimco, T Rowe Price and Capital Group, all suffered net-redemptions of between $17.9bn and $32.2bn in the first six months of 2020, according to Morningstar. On the other side, BlackRock raised almost $74bn across its mutual funds, while Vanguard noted net inflows of $67.7bn. In addition to the trend of investors turning to index products for equity exposure, investors are now becoming more and more willing to use passive funds for fixed income. This gives big bond managers such as Pimco definite advantage. Investors globally added a total of $98bn to fixed-income index funds in the first six months of 2020, pulling $50bn from non-index products at the same time. Such an environment has led to many active managers merging with competitors to cut their cost base, allowing them to decrease their fee levels to better compete with passive offerings.

It should also be noted that fee compression has been affecting the already low-cost passive space as well, as larger players attempt to increase inflows by drastically cutting their fee levels. In 2018 Fidelity, one of the US giants, unveiled four indexed mutual funds with no annual fees and their move gained a lot of attention. Back then Vanguard was offering some of the cheapest indexed products of the market, BlackRock, being the world’s largest issuer of ETF funds, could afford offering products that charged less than $1 for every $1,000 invested and Fidelity had no other choice but to follow. As a result of several moves of this sort from different investment managers around the globe, investors are paying today roughly half as much as they were nearly two decades ago and about a quarter less than five years ago. This again is leading to players in the passive space engaging in consolidation to realize revenue synergies and cut their fee levels.

It should also be noted that LPs are looking to decrease the number of managers they have relationships with and are looking to dedicate more in AUM to their managers. This essentially means that demand is increasing for one-stop-shops with expertise in the entire spectrum of product offerings. This includes managers that have offerings in active, passive, equities, fixed income, alternatives, ESG…etc. Thus, many managers are making selective acquisitions of smaller players to expand their product lines. Examples include Franklin Templeton’s acquisition of alternative credit specialist Benefit Street Partners in 2018 and Australian Financial Firm Perpetual’s purchase of ESG specialist Trillium Asset Management at the beginning of this year.

The industry is beginning to consist of either massive mega players or unique boutiques with strong reputation for firms’ key asset classes among allocators. This leaves asset managers who have neither the scale nor specialist expertise left far behind. And just to provide some comparison, the world’s five largest asset management companies, BlackRock, Vanguard, UBS, State Street and Fidelity International, hold $22.5tr in AUM combined, which is higher than the GDP of the United States. During this massive wave of consolidation, Invesco’s chief executive is predicting that a third of the asset management industry could disappear by 2024.

Acquisitions of asset managers by investment banks

Over the past couple of years, we have seen significant growth in the asset management divisions of major players within the financial industry. We will be focusing more specifically on the expansions at Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley over the period of 2014-2019. Goldman Sachs has had its assets under management (AUM) increase substantially by 66%, from $1.117tn to $1.859tn. In addition to this, its asset management revenue has had an explosive growth since 2014, increasing by more than 50% from $5.75bn to $8.97bn. Moreover, Deutsche Bank has increased its AUM from $584bn in 2014 to $768bn in 2019. Its asset management division-specific revenue has however remained more or less stable over the past 5 years, fluctuating around €2.5bn. Morgan Stanley on the other hand, has showed consistent growth in both its assets under management and its revenues coming from its asset management division. Its AUM from 2014 to 2019 have increased from $394bn to $500bn showing a 27% increase while its asset management revenues have increased 28%, from $2.049bn to $2.629bn. It should be noted that proportionally, the share of asset management revenues at banks has been increasing. For example, Goldman Sachs’ $1.86tn asset management division contributed 24.5% of the net revenues in 2019 compared with 16% in 2014. Goldman Sachs’ investment banking revenues on the other hand, accounted for 19% and 17% of the net revenues in 2014 and 2019, respectively.

In this race to increase the develop of their asset management businesses, investment banks have been engaging in significant M&A to increase their scale and diversify their product offerings. Goldman Sachs, for instance, acquired Standard & Poor’s Investment Advisory Services in 2019 and Rocaton Investment Advisors in 2018. The firm has also been named as a potential buyer of Wells Fargo’s asset management unit, a money manager with $578bn in AUM. Morgan Stanley, as previously mentioned, has recently announced the acquisition of Eaton Vance. It also acquired online brokerage E*Trade in 2020 and employee stock plans manager Solium Capital in 2019.

One reason investment banks are expanding into asset management is that this division provides banks with a more reliable revenue stream. When compared with investment banking division revenues, asset management revenues show a lot less volatility, and instead exhibit stable and predictable cash flow characteristics. Morgan Stanley for instance had its investment banking revenues decrease 4% from 2014 to 2019 while its asset management revenues increased 28% over that period. Moreover, Goldman Sachs’ investment banking revenues decreased 5% over the past 5 years whereas their asset management revenues increased by 56%. Even in times of difficulty when all divisions are underperforming relative to the previous fiscal year, asset management revenues prove to be more stable due to their fee-based structure. For example, Deutsche Bank’s investment banking revenues in 2019 dropped by 16% relative to its 2017 performance, while its asset management revenues only dropped 7%.

In addition, developing in-house asset management products allows for cross selling opportunities and vertical integration alongside a closed architecture system. As investment banks become more prominent players in the asset management industry, a bank’s opportunities to encourage its own clients to invest in internal funds may arise if the firm operates under a closed architecture model. However, it’s important to note that this type of sales system could potentially direct bank clients towards inappropriate funds for the bank’s benefit. Most banks have adopted an “open architecture” model whereas others such as UBS have adopted a “guided architecture,” which is a hybrid of the open and closed model: mixing the sale of in-house funds in addition to external funds.

Expanding one’s asset management division can also lead to synergies with the investment banking arm. These synergies could arise from co-investment opportunities with clients of the firm. In the case where a co-investment takes place, other investors are enabled to partake in potentially extremely profitable deals without paying the high fees that private equity firms usually charge. For example, if an investment bank is advising a PE fund/investor on an investment in a particular type of firm, the asset management division can perform a co-investment along with the PE firm.

In regard to the outlook for investment banks and their asset management divisions, it is forecasted that these banks will continue to grow their asset management arms with the goal of increasing the already strong and reliable revenues that these divisions provide while also aiming for higher profit margins. Through expanding and diversifying the range of products that these investment banks can offer, they will soon enough have built enough scale to be able to provide a full-service offering. This includes everything from passive investment capabilities, such as ETFs, to more illiquid strategies, such as real estate, fund of hedge funds, infrastructure, and private credit capabilities.

0 Comments