Introduction

Following the recent re-opening of the IPO market, CVC Capital Partners, the venerable European private equity firm, is said to be preparing to go public. This raises the question of whether doing so is a good idea. It is easy to say that going public is just a way for the company founders to cash out their shares, but we believe that the rationale behind going public is more nuanced. Below, we try to give a brief history of private equity firms going public, before evaluating both the merits and risks of doing so, by looking at both the effect going public has on the general partners as well as the limited partners of the fund.

Background & Timeline

The pre-echo of private equity (PE) firms going public started in the mid-2000s when multiple funds intended to raise permanent capital through publicly listed investment vehicles. The motivation behind this was first misunderstood, as some felt that financial sponsors were giving up one of their unique selling points, namely independence from the volatile public markets. The pioneer in going creating a public private equity vehicle was Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) [KKR: NYSE] in May 2006, with its permanent investment vehicle KKR Private Equity Investors (KPE). KPE raised $5bn in an IPO, which was more than three times what it had expected. Other PE firms, including Blackstone [BX: NYSE], wanted to follow suit, but KPE’s IPO appeared to have soaked up all demand for such vehicles. That, combined with KPE’s stock decline of 27% at the end of 2007 and 54.2% in first quarter of 2008 when compared to the IPO price, removed demand for such IPOs.

KPE’s poor performance was one of the motivations for taking the management companies, instead of individual funds, public in order to raise permanent capital, starting with Blackstone’s IPO. In its IPO, the firm sold a 12.3% stake for $4.1bn on June 21st, 2007, marking the largest U.S. IPO since 2002. As some of its incentives for going public, Blackstone mentioned access to new sources of permanent capital for reinvestment and expansion, provision of publicly traded equity currency for better flexibility in pursuit of new acquisitions, enhancement of the firm’s brand, expansion of financial and retention incentives for the firm’s employees through issuance of equity-related securities and, lastly, the realization of the value of equity held by existing owners.

Blackstone’s successful IPO and investors’ desire to realize their portions of value locked into their firms led to a frenzy of IPOs in the next year:

KKR was the first to follow, filing for a $1.25bn ownership interest sale in July 2007. The flotation was, however, repeatedly postponed due to unattractive valuation prospects following the onset of the global financial crisis

In September 2007, Carlyle Group [CG: NASDAQ] sold a 7.5% stake to Mubadala Development Company, owned by the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund, for $1.35bn, which valued Carlyle at $20bn.

In January 2008, Silver Lake Partners sold a 9.9% stake in its management company to California’s retirement fund for $275m.

Before filing with the SEC in April 2008, Apollo Management [NYSE: APO] offered a private placement of shares, some owners of which were later permitted to sell their shares on the New York Stock Exchange.

When Blackstone first went public, it offered shareholders more than half of its combined management and performance fee-based profits. This model was followed by KKR, Carlyle Group and Apollo Global Management stake offerings.

With the initial increase in the number of publicly traded private equity firms, it is important to look at the intentions behind selling an ownership interest to the public. Looking at the growth opportunities’ prospect, access to capital gained by offering shares is vital for a PE firm’s performance. The newly available permanent capital can be used for hiring new talent, paying down debt or even the acquisition of new companies, an example of which would be Blackstone’s purchase of Credit Suisse’s secondary private equity business Strategic Partners. Furthermore, an IPO provides liquidity to the owners and investors of the management company, who can realize their gains by selling own shares on public markets. Further, going public enables firms to pay their employees in stock, which, depending on the company’s performance, may prove very valuable. Finally, a PE firm’s presence on the public market enhances brand visibility which comes with the benefit of attracting new investors, business partners and clients.

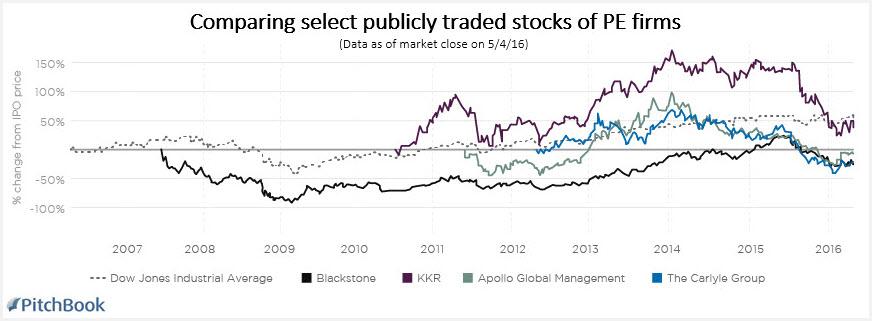

Source: PitchBook

However, private equity firms’ public offerings have been criticized in the decade leading up to 2019. Shares of publicly traded private equity firms performed poorly in the time frame. To provide a more tangible overview, S&P returned 5.65% annually from 2007 to 2019, while Blackstone’s only returned 1.68%, spending the majority of the post-financial crisis years below its IPO price. In the 7 years up to 2019, S&P returned 10.69% annually against Carlyle Group’s -0.93%, and Apollo’s 7.79%, outperforming both PE firms. Performance of select public PE firms in comparison to Dow Jones Industrial Average can also be seen below.

When Brookfield [NYSE: BN] agreed to take majority stake in Oaktree for $4.7bn in 2019, the latter was trading at $43.83 per share, only marginally above its $43 per share IPO listing in 2012. The likes of Steve Schwarzman and Leon Black (Co-founders of Blackstone and Apollo Management, respectively) then expressed their concerns over the public listing of private equity firms. Apollo’s founder stated: “We like to say that we have built a unique platform which encompasses value, growth and yield and the market doesn’t get it… There is a disconnect with the market.”

The lackluster performance of listed private equity firms following the financial crisis deterred many firms from going public. For those firms that nonetheless wanted to raise capital, selling an equity stake to private equity firms specialized on buying stakes in private equity management companies, the so-called GP stakes funds, proved more attractive. One such firm, Dyal Capital, bought passive minority stakes in some of the largest private equity groups including Leonard Green, Silver Lake, and Bridgepoint. In the beginning of 2019, Dyal Capital had $15bn in assets under management (AUM) and about 40 stakes in hedge funds and private equity groups.

EQT [EQT: STO], a Swedish private equity group with $40bn AUM at the time of announcing its plans of going public in mid-2019, mentioned the desire to become truly pan-European with the proceeds from going public. It showed strong performance in the years leading up to the announcement, generating net internal rate of return of about 20% on its private equity funds. The CEO of EQT, Christian Sinding, stated that EQT should be “relatively straightforward to understand” as an opposing view to Leon Black’s statement some weeks earlier. Perhaps, he was right. In the opening day, EQT’s shares jumped from initial offering price of SEK67 to SEK84.5, with current market price of SEK222 and a peak of SEK542.6 in November 2019.

Investors mainly attributed this strong performance of the IPO due to the novel way it distributed earnings to public markets investors. It offered them one-third of carried interest performance fees and all its management fees, which was a very different structure to that used by firms going public a decade earlier. Giving public investors all of the management fees proved attractive to the public markets, as they value them more highly (25-30x multiple) than the very volatile carried interest performance fees (5-10x). As a result of EQT’s success with the new earnings distribution structure, other private equity firms changed their distribution model to mirror EQT’s leading to a significant re-rating of the enture sector. After languishing for years, the shares of companies including Blackstone, KKR, and Apollo, significantly outperformed, with Blackstone recently joining the S&P500 index.

As a result of the renewed investor interest in private equity management companies, other private equity firms started going public once more. Bridgepoint [LON: BPT] listed on the London Stock Exchange soon after EQT’s IPO, gaining a valuation that rose to more than £4bn. Although the IPO raised controversy due to lack of explicit reporting on executives’ carried interest payments, it was received well on the market, with a sharp rise in stock value from £3.5 per share in July 2021 to more than £5 in September 2021. This performance can be attributed both to the lose financial conditions at the time, as well as Bridgepoint giving up much of its management fees. TPG [NASDAQ: TPG] too followed EQT’s suit, restructuring its finance to give investors a larger claim on management fee-based profits and the dealmakers a larger share of performance fees. It went public on January 12, 2022, raising $1bn in its IPO at a valuation of $9.1bn. It is currently trading at approximately the same price as the IPO at $29.5 per share.

CVC and General Atlantic, encouraged by the new success of private equity company IPOs, are now looking to go public as well. CVC Capital Partners is one of Europe’s largest alternative investments companies, having recently closed a €26bn fund, the largest private equity fund ever. It is planning to restructure its operations similar to what EQT first offered in 2019. CVC’s plans for IPO and current expansions into different industries makes for excitement around news about the firm. It has recently acquired stakes in brands from Debenhams to Formula 1, La Liga and even diversified into infrastructure through its acquisition of DIF Capital Partners for €1bn last month. CVC’s IPO will potentially happen in November this year, providing that the IPO markets will remain receptive to new listings. Quite similar to CVC, Ve eral Atlantic is exploring its IPO options and is diversifying the range of its offerings. Its acquisition of Iron Park Capital earlier this year allowed to expand into credit business.

Advantages of Going Public

Going public is a major liquidity event for founders, shareholders and employees with shares of any company; private equity firms are no different. Founders of privately-held private equity firms as well as general partners in the funds typically hold large illiquid equity stakes pre-IPO and cannot struggle to sell these shares on the private market. Going public gives the partners the chance for a sizable payout, especially in light of the dizzying valuations some of the firms have floated at. When Blackstone went public in 2007, co-founder and CEO Stephen Schwarzman’s stake in the firm was valued at roughly $7.5bn – a little more than media tycoon Rupert Murdoch’s stake in News Corp [NWSA: NASDAQ] and more than double the value of the $3.3bn stakes held by Google [GOOG: NASDAQ] co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page when the tech giant went public in 2004. General partners of the fund who have equity stakes in the firm also experience similar windfalls at IPO, which has interestingly stirred some controversy behind the doors of CVC Capital Partners. Partners on the verge of retirement have stayed on at the firm in anticipation of their upcoming IPO whilst not contributing their fair share to the workload.

Raising permanent capital through an IPO can also allow a private equity firm to expand into new geographies as well as asset classes. This is particularly relevant considering the recent trend of many of these firms looking to be a global player in a variety of asset classes, spanning from private equity, private credit, real estate and infrastructure. This can typically help fundraising efforts for firms, as they can offer a larger range of products to investors and can be a one stop shop for their capital by offering diversification across financial markets. Michael Patanella, Grant Thornton national managing partner in asset management recently said: “Everyone wants less complexity in life, and I think if you can offer five different types of investments versus one, you’re going to be more competitive.” An IPO can strengthen a firm’s balance sheet and give it the capital necessary to set up operations in new markets, typically through acquiring an asset manager that specializes in a specific geography or asset class. M&A activity in the alternatives asset management industry has led to a wave of consolidation in recent times, with TPG capital [TPG: NASDAQ] paying $2.7bn in May to acquire Angelo Gordon, a firm with particular expertise in credit and $73bn assets under management. This results in TPG expanding its client base, increasing its assets under management to $208bn and being able to offer a wider range of products to its limited partners in pursuit of being a one-stop shop for multi-strategy asset management in alternative markets. Private equity firms may even opt to acquire a firm that operates in a different region of the world and geographically diversify their product offering. Ares management [ARES: NYSE], for example, announced in July the acquisition of Singapore-headquartered private equity firm Crescent Point Capital, with around $3.8bn of assets under management. The transaction highlights a continuation of Ares’ global expansion and allowed them to acquire the human capital who have buyout expertise in the Asia Pacific markets. Ultimately an IPO is one way that a private equity firm can raise the capital required to expand in the pursuit of becoming a global alternative asset manager for investors.

Being a publicly listed private equity firm can also go a long way for marketing and fundraising efforts, particularly for firms that operate in the middle market or in a specific niche. Being publicly traded can build the reputation of these companies and instill trust in potential limited partners when raising new funds. This was particularly relevant for Ares Management, an alternative asset manager with a deep-rooted focus on private credit when they went public in 2014. Since they were started off in the niche of private credit they were not in the headlines as much as some of their private equity-focused counterparts and so their IPO was a great way to make headlines and build the brand of their firm. The final rationale behind taking a private equity firm public is to better align incentives for employees within a firm. Having stock as part of compensation packages is a very common way of motivating employees and aligning incentives – as the firm performs better, the stock price rises and the value of those shares held by employees also rises along with their wealth. This is obviously much harder to value in a privately held company where the shares are not associated with a ticker. Consequently, it is much easier to align incentives and motivate employees with stock of a publicly listed firm, as it is not only more liquid but is also a direct reflection of company performance. Increased motivation of employees may end up with the firms posting better returns for their limited partners and so going public can also be beneficial to them.

Disadvantages of Going Public

One disadvantage is that managers lose their highly valued secrecy. Going public brings several disclosure requirements, such as the compensation for top managers. This can negatively impact the public image of private equity firms, such as when Steve Schwarzman made headlines for his $1.3bn “paycheck”. This gives the press and politicians an angle of attack, contrasting the high private equity pay packages with the job losses sometimes caused by private equity ownership. This could lead to tougher regulations, such as Germany’s latest effort to crack down on private equity investments in medical practices. Whilst firms such as Bridgepoint have managed to avoid disclosing carry and the compensation of top executives, going public will always incorporate some loss of privacy.

More importantly, however, going public can entail fundamental misalignment of interest between the general partner (i.e., the private equity company) and its investors (limited partners). Public markets primarily attribute value to the management fees that private equity investors generate, rather than their performance fees. As mentioned above, the reliable management fees are valued at 25-30x, whilst carried interest, due to being volatile and dependent on financial market conditions, is valued at 5-10x. If the management has much of their wealth tied up in the value of the private equity firm, as is the case for large public private equity firms such as Blackstone or KKR, they are strongly incentivized to raise as large a fund as possible, even if that means sacrificing returns due to larger funds, as the appreciation of the company on public markets resulting from raising huge funds will likely exceed the foregone carried interest payments due to worse performance of the funds. Evidence from public equity funds shows a negative correlation between fund size and returns (Yan, 2008). While there is less evidence for private equity investors yet, recent fundraising comparisons support a similar conclusion. Further, raising large funds means that you can only pursue the largest opportunities, where it is harder to make truly outstanding returns. After all, if you are already very large, it will be hard to grow further in the market, for example. Berkshire Hathaway’s declining returns as the company grew are a good piece of anecdotal evidence to that end. While publicly listed Apollo, Blackstone and Carlyle missed their fundraising targets, some of their private peers such as Warburg Pincus exceeded their target, just recently raising $17.3bn. Warburg’s CEO also cited the firms focus on private equity as a key driver for the fundraising success. In contrast to its public peers, Warburg Pincus has not diversified into other alternatives such as Credit or Infrastructure. As a result, the once equal-sized Blackstone now commands 10x as much AUM as Warburg. However, this can also bring conflicts of interest, such as when different investment teams within one firm look at the same target (Henderson, 2009). Perhaps, focusing purely on one strategy might be a key differentiator of alternative investment managers in the future.

Conclusion

From the perspective of a partner or founder of a private equity fund, going public is very attractive. You are able to crystallize the equity value of the company that you have built up over decades and also tie up talent to your firm for longer, by providing them with restricted share awards. From the perspective of an investor, however, the private equity firm going public is not necessarily great news. After all, this means that the management of the firm will now be more focused on creating a great business that is attractive for public market investors, rather than purely maximizing the returns the firm generates for Limited Partners. Hence, the company may diversify into new business lines and raise more money faster, arguably leading to lower returns to limited partners. One final thing to note is that public private equity firms commit themselves to paying out part of the fees that they receive. These are no longer available to compensate junior talent, possibly making the public companies less able to maintain top talent in the long run. Taking the examples from investment banking, firms that have gone public, most notably Goldman Sachs, have failed to maintain the lustre that they had as private partnerships, due to scrutiny on quarterly results and constrained costs. Hence, given somewhat misaligned interests between general and limited partners, it will remain to be seen whether going public was the right way to build alternative asset management firms that will stand the test of time.

0 Comments