Introduction

2018 was a somehow controversial year in IPO terms, with Q1, Q2 and Q3 building a strong momentum for companies to go public, and Q4 eroding the optimism recorded in the preceding timeframe. Unfortunately, 2019 has opened with the same negative outlook, with scheduled IPOs all throughout the world being put on hold in anticipation of better conditions. Despite this initial negativity, worldwide markets in the first four months of this year have also welcomed many new big companies, which challenged the current uncertainties by hitting the markets with strong fundamentals and willingness to succeed.

This article will address all the reasons behind the trends depicted above, specifically targeting recent global market conditions, as well as the potential drivers and expectations driving an IPO process in this period. It will also address the immense number of IPOs populating the technology sector, and the implications behind this trend. In the coming weeks the second article in our IPO series will be published, which will cover the big problem analysts now face in regard to tech IPOs: how do you value unprofitable, cash-burning companies that lack comparable firms?

Background

In recent months, equity markets’ performance throughout the world has experienced the same trend, with a worrisome slowdown from October 2018 followed by an optimistic beginning-of-the-year evolution. This pattern is particularly found in larger indexes such as the S&P 500 (for the US market), and in the EURO STOXX 600 (for the European market). Specifically, in 2018 the former index recorded the worst yearly total returns ever since 2008, even going negative by 6.2%. According to analysts, this behaviour is rooted in the massive sell-off starting in October, with investors already foreseeing clouds ahead. Fortunately, 2019 has begun with a positive rally, although this could be potentially linked to frequent stock buybacks from major corporations trying to wipe out the excess cash they had on hand after Trump’s tax-cuts. Similarly, in 2018 the latter index, which represents a proxy for the European market as a whole, also recorded the worst performance ever since the last financial crisis, hitting a -13% total annual return lower bound. Despite pessimistic expectations, what is worth pointing out is that 2019 saw an impressive improvement in optimism and investors’ appetite for risk, paving the way for a positive trend and impeding bear market conditions.

When compared by means of the MSCI Index, the US equity markets seemed to have outperformed the European ones, in large part because they outperformed the MSCI World benchmark, whereas the European markets registered less successful results.

Other equity market factors that are heavily influencing IPO frequency are greater liquidity, volatility, and uncertainty. In the current market environment, IPOs are encouraged largely because of excess liquidity, which Central Banks have been systematically injecting over the years since the crisis. Although the Fed has already started a normalization process–with interest rates hikes both behind and ahead–and the ECB has ceased Quantitative Easing in late 2018, markets seem to still be well equipped with cash.

On the other hand, IPOs are nowadays discouraged by several factors, ranging from the heavier and heavier regulatory requirements imposed on companies going public, to the aforementioned scheduled interest rate hikes. Furthermore, short-term volatility in the markets worldwide has significantly increased on a yearly base. Another driver of uncertainties is to be found in the puzzling trends of currency and oil markets. However, the main source of distress for the equity markets is rooted in the current geopolitical tensions and worldwide economic slowdown. Indeed, as empirical evidence will demonstrate here below, Brexit, US-China trade wars, US tariffs imposed on European goods and the expectations of another economic slump ahead are feeding investors’ doubts–making Q4 2018 and Q1 2019 suspiciously quiet in terms of IPO volumes. Specifically, Q1 2019 has seen only 199 IPOs worldwide (-41% against Q1 2018), raising only $13.1bn proceeds (down 74% against Q1 2018).

Having a closer look at each macroeconomic area, the article will now provide the main figures and outlooks for the Americas, the EMEIA and ASIA PACIFIC, respectively, so as to ground the trends explained above on solid empirical evidence.

The Americas

In 2018, the American markets supported 261 IPOs, up 14% YOY, yielding proceeds of $60bn, which represent a 16% YOY increase. The median deal size was approximately $99m (down 13% against 2017). Naturally, the US accounted for about 79% of the total IPOs by deals number and 88% in terms of proceeds. These figures made 2018 look like a positive year for flotations, which was assisted by the presence of 26 unicorns and a positive post-IPO price performance. Indeed, first-day average returns of 15% and an average offer-to-current performance of 10.6% have kept investors engaged while encouraging more companies to hit the market, despite the increase in volatility as grasped by the CBOE VIX (up 87.9% YTD as of December 31st, 2018).

In Q1 2019 the trend seems to have started reverting, in accordance with expectations. Indeed, the number of companies going public (i.e. 31) has decreased by 44% when compared to Q1 2018. Similarly, proceeds have fallen by 83%, hitting a $3.3bn lower bound. The median deal size has settled at a lower level as well, falling to $69m. Anyhow, what CEOs should be confident about is the significant decrease in short-term volatility, as captured by the CBOE VIX, which recorded a -52.4% YTD as of March 31st, 2019.

In both 2018 and Q1 2019, the sectors enlivening the American IPO arena have been tech, health care and industrials.

EMEIA

Turning the limelight to EMEIA, IPO trends seemed to have been heavily affected by geopolitical tensions, mainly concerning Brexit and political changes in Germany and Italy, together with US trade and tariff uncertainties. Despite these concerns, EMEIA has turned out to be the world’s second-largest IPO market, accounting for 32% of global volume and 23% of global proceeds in 2018. However; in the same year the markets have welcomed only 432 IPOs (-16% against 2017), with $47.7bn proceeds (-26% against 2017), and a median deal size settling at $83.2m. Anyhow, thanks to a first-day return of around 10%, and IPO shares systematically beating the main market indices, the negative figures highlighted above have not significantly undermined investors’ confidence in the EMEIA IPO markets. But at the same time CEOs expressed their concerns about the rising volatility, as captured by VS STOXX (up by 27.4% YTD as at December 31st, 2018), VDAX (up by 29.7% YTD) and VFTSE 100 (up by 76.3% YTD).

Perfectly matching expectations, 2019 opened with a huge slump in IPOs, down by 65% in volume and by 93% in proceeds. Indeed, in the first three months this year, only 42 companies began listing on the market, raising a total $1.4bn proceeds, with a median size of about $18m. Anyhow, a fist-day average return of 4% and an average offer-to-current performance of around 46% might feed the sentiment of a bit of a boost, and restore investors’ confidence in the newly issued shares, eventually encouraging on-hold IPOs to defrost and heat the markets. Moreover, a declining volatility should erode some of the CEOs’ concerns about the successful implementation of an IPO process, since VS STOXX was down by 42.8%, VFTSE by 43.2% and VDAX by 37.9% YTD, as of March 31st, 2019.

Similar to the American markets, the EMEIA arena has been dominated by transactions in the technology, industrials and consumer products fields. Examples can be found in Aston Martin Lagonda Global Holdings plc (UK, $1.4bn), Knorr Bremse AG (Germany, $4.4bn) and Adyen BV (the Netherlands, $1.1bn)’s flotations.

Asia Pacific

Lastly, some attention will be devoted to Asia Pacific, which has been the worldwide leader both in 2018 and in Q1 2019.

Indeed, in 2018 all these regions saw 666 companies going public, raising proceeds for $97.1bn. Anyhow, what absolute figures fail to show is the puzzling trend they embed: the volume of transactions was down by 31% on a yearly basis, while proceeds were up by 28% against 2017. The reason behind these misleading changes is to be found in the presence of massive deals (such as SoftBank’s listing) and unicorns (especially in Japan, with the flotation of Mercari and MTG Co. Ltd), building strong amounts of proceeds, even though the number of companies going public had decreased. Adding distress to the already-delicate market conditions, volatility in the Asia Pacific markets increased throughout 2018, as captured by Hang Seng Volatility Index, up by 36.6% YTD, as of December 31st, 2018. Stepping into 2019, investors were openly seeking more traditional IPOs, ideally involving companies from the oil and gas industries.

In Q1 2019, in line with the worldwide trends depicted above for the Americas and the EMEIA, Asia Pacific experienced a negative trend both in the number of deals (settling at 126, i.e. down by 24% against Q1 2018), and in the proceeds (settling at $8.4bn, i.e. down by 30% against Q1 2018). Anyhow, once again in line with both American and EMEIA trends, the market volatility seems to be pursuing a declining trend, wiping out some of the uncertainties connected with the success of an IPO process, since the Hang Seng Volatility Index fell by 39.5% against March 31st, 2018 figures.

Similar to the American and the EMEIA markets, the Asia Pacific arena has also been dominated by transactions in the technology, industrials and materials fields. The most representative example of the massive IPOs taking place on the Asian markets can be found in the SoftBank Corp.’s case mentioned above (Japan, $21.1bn).

Everything considered, analysts are confident about a worldwide positive rally ahead, expected to be triggered in the second half of 2019. According to them, there are unicorns and mega deals in the pipelines of markets all throughout the world, which will be welcomed by investors’ appetite and well supported by a good amount of liquidity. According to the same analysts, investors will be attentively looking for sound companies, grounded on solid fundamentals.

Why IPO?

2019 is and will be a year of IPO bonanza: Lyft, Uber, Airbnb and plenty of other unicorns have listed or will list on public markets. The reasons for choosing an IPO are mainly two: the pragmatism of economics and the passion of personal achievement. As for the first rationale, unicorn companies may want to take advantage of the rich pools of capital and liquidity before an economic slowdown hits, thus deciding to list. The predicted recession on the horizon could bring a slowdown in economic growth, which, when combined with an increase in interest rates, could suck the liquidity from the market and lower IPO valuations in the future. The second reason for choosing an IPO is that founders may want to join the exclusive listed global tech hub. Passion is at the heart of a unicorn’s decision-making and founders may want to become a part of the inner circle of highly successful entrepreneurs, as well as feel the adrenaline rush that comes with the bell on the floor of the stock exchange. However, many would argue that a company’s “choice” to IPO is far more affected by external market conditions than their own desires, financial or otherwise.

The scientific literature tends more and more to consider the thesis of market timing, which encourages many firms to precipitate their IPO decision (Baker and Wurgler, 2002). Ritter and Welch (2002) put forward the idea that market conditions are the most important factors in the process of deciding to launch an IPO. They noticed that IPO volumes decrease rapidly in bear markets. In fact, lower markets have discouraged several firms from launching IPOs; instead preferring to put these launches off. According to Lowry (2003), economic recovery and investor optimism can encourage a corporation to launch an IPO. Thus, the IPO decision is influenced both by exogenous economic conditions and by a firm’s own financing needs, but to a much greater extent by the former. Lerner et al. (2003) showed that in very unfavorable market conditions where introduction prices are weak, only those corporations who had urgent short-term financing needs or future high-yielding projects would continue with an IPO launch. Another subject of recent research is how technological change affects IPO waves. The arrival of new technology demands very fast development and requires considerable investment. According to Stoughton et al. (2001), if a leading corporation—meaning one which holds the patent to or initiated the original technology—decides to launch an IPO, it provides enough information on its future cash flow and enables investors to better assess the sector. Other “follower” firms profit from this opportunity to launch an IPO. This theory was confirmed by Lowry (2003) who proved that technological shock created significant capital needs and drove several companies to launch an IPO with an aim to raise funds. However, this theory was contradicted by Helwege and Liang (2004) who found that technological change does not fully explain IPO waves but rather the arrival of other firms seeking out capital. This example can be seen in internet firms in the 1990s, followed by biotechnology companies and more recently by social networks. Competition on the stock market means that investors are becoming scarcer and late arrives will not be able to access the market under the right conditions (Hsu et al. 2010).

Regardless of what may have caused them, most IPOs have several advantages: they serve as a catalyst with speed and scale for accelerated growth, they open access to growth capital availability and a new external investor base, they offer a liquid market as well as further wealth creation and diversification. In addition, they give a boost to brand profile and allow unicorns to open new markets and attract new customers, while also helping retain great talent. Lastly, they provide stronger governance and transparency, allowing a company to improve its professionalism and establish itself as a bona fide market player. On the other hand, IPOs have disadvantages too: greater scrutiny through increased transparency and capital market regulation, susceptibility to volatility in the markets, a greater burden to meet compliance requirements and regulatory oversight, and increased pressure on the company to deliver on promises in the public spotlight.

It is also worth mentioning direct listings: in fact, unicorns can directly list existing shares without issuing new shares and pay a substantial smaller amount in fees. However, a direct listing isn’t for everyone, size matters and it can work well for companies that already enjoy brand recognition and a significant private market valuation, such as unicorns (Spotify is an example of a past direct listing, Slack will undergo the process this year). A direct listing can further strengthen a brand and build confidence in the unicorn’s equity story, and it has the option of taking the second step of issuing new shares to raise further capital.

Why the wait?

The average age of US technology companies that went public in 1999 was four years old, according to Jay Ritter. Of the more than 35 public software companies that reached valuations upwards of $10bn from 2004 to 2015, only six achieved that level before going public. The rest reached it an average more than eight years after their IPOs. Ritter’s research shows that the average age of technology companies going public in 2014 was 11 years, and private funding rounds have generated an increasing number of decacorns and unicorns.

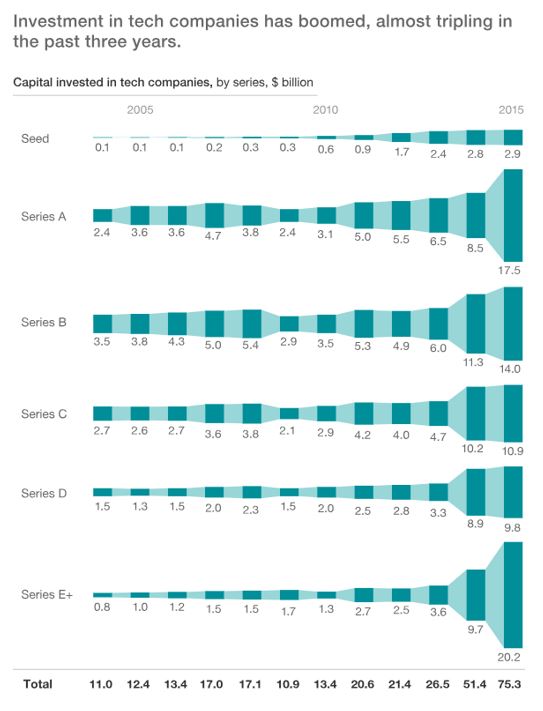

There are several reasons for this new dynamic. The US Jumpstart, also called the US Business Startups (JOBS) Act, which passed into law in 2012, increased fourfold the maximum number of shareholders a company can have before it must disclose financial statements. In addition, the private capital available to software start-ups has rocketed up in recent years– in just 2014 and 2015 the capital invested in private companies almost tripled, to about $75bn in 2015 from around $26bn in 2013. Moreover, public markets seem to prefer larger tech companies. For instance, Jeremy Abelson and Ben Narasin found that public markets assign larger businesses a higher multiple at the time of their IPOs and afterwards.

The influx of capital available to private tech companies and the overcapitalization of many unicorns and decacorns have not been without consequences. In the first three months of 2016, several private software companies faced valuation pressure in the form of down rounds, including Pinterest which will have a “down round” IPO. Moreover, the average delay in mounting IPOs forces venture investor to wait almost three times longer than they did a decade ago, so private-market activity has ticked up significantly as employees and investors seek liquidity. But the consequence of delayed IPOs affects also the public market. In fact, the public market investor doesn’t get access to a lot of the growth, and that just creates wealth inequality, because all that growth opportunity is given to people who are already wealthy.

0 Comments