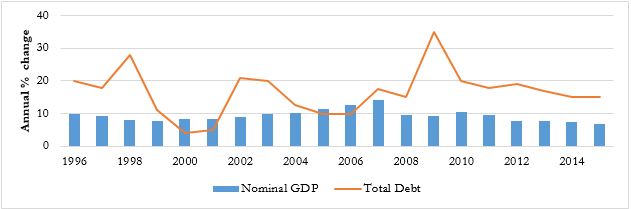

Once again Soros has bet against China. This time it is with regards to its mounting debt, comparing it to a pre-crisis US in a recent interview with Bloomberg. He justified his opinion by looking at the booming credit market and growth of the inefficient state owned zombie firms. Measuring the level of debt to GDP, which is around 249%, and the annual growth of credit at around 15%, twice that of its GDP, we understand the source of concern. The speed of accumulation of debt is alarming: in 2007 debt accounted for only 149% of GDP. The key problem is that Beijing has tried to boost domestic growth by providing cheap debt to its various provinces and SOEs’ (state owned enterprises) in order to maintain high growth levels and scale up production. As we can see in the graph below, most often the spikes in the percentage change of total debt coincide precisely with times when nominal GDP hasn’t increased too much and that is particularly true for the period of 2007-2009.  Source: BSIC

Source: BSIC

First and foremost back in 1999, specifically made asset management organizations purchased NPLs (non-performing loans) totaling Rmb1.4tn ($216bn), which were at the time about 20% of total national output, off the nation’s largest state banks at full value, as opposed to writing them off, paying with 10-year bonds. At the point when the bonds came due in 2009, following 10 years of rapid economic growth, the NPLs obtained 10 years before were worth under 5% of GDP, in principle making them much less demanding to discount. A similar situation occurred in 2010 by purchasing an additional 4.4 trl CNY with government bonds postponing the payment until 2019 still hoping that it will become a smaller part of GDP until then. But these numbers may be too optimistic as some financial specialists claim that about 15% of all commercial lending in China may be at risk.

The whole debt episode started in 2007 as a post-crisis reaction from the Chinese government when it provided some 4 trn CNY to its local governments in order to stimulate growth and expansion. As we can see from the graph above this is the period when the largest % change in total debt occurred. China’s Q1 GDP growth in 2008 slumped to 6.8%, compared to 14.5% in Q2 2006. To stabilize the economic growth, the central government launched its financing program.

Second stage is from 2010 to the end of 2014. The economy was back on the track however, risk emerged as the level of local government debt surged. In 2012, the size of municipal bonds increased by almost 150%. Local governments usually do not raise funds directly but through entities known as local government financial vehicles (LGFVs). Due to the high borrowing costs and lack of transparency of those vehicles, central government urged to enhance management on LGFVs. Since most borrowings are from commercial banks, managing systematic risk of the banking industry has become one of the most urgent issues.

The third stage came recently with the slowdown of the Chinese economy. On the one side, local governments are forced to keep borrowing money to maintain cash flows on existing projects and GDP performance. On the other side, decreasing investment returns cannot even cover the interest expenses. In 2015, Chinese government decided to restructure 1 trillion CNY existing high-yield debts into lower-cost bonds. Banks can use those new local bonds as collaterals to tap a variety of loans from the central bank. This is again a tool which they use in order to postpone the payment of loans for future times. However, rising default risk has made many banks cautious on participating in the program.

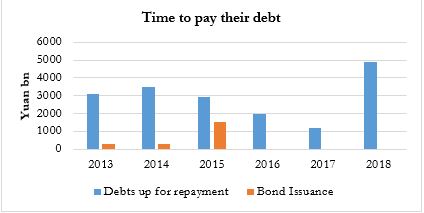

Source: BSIC

As we can see from the graph, restructuring makes up only for a small portion of the overall debts and local governments will face huge repayment pressure in the next few years. It is estimated that at least two more rounds of debt-for-bond swap will be launched but it requires fundamental reforms on fiscal system and debt management to defuse the crisis.

But let’s be clear that there are a few big differences between the Chinese and the pre-crisis 2007 US situation: the Chinese population financed its own debt, as households are the main lenders to banks, which then in turn lend out all the loans. Also China still has room to grow at around 6-7% average predicted yearly growth. Although it is lower than its peak moments, it is still pretty high when you consider mature markets. Thus the way that the government handles its current debt is by postponing it to future dates, hoping that then it will become a lower part of its GDP and it would be a lot less painful to write off. However, this cannot go on indefinitely and as soon as 2019, when some 4.4 trn RNB are due to be repaid, someone will have to pay the bill. Finally another thing to note is that the Chinese government still has about 21 trn RNB of foreign denominated reserves so financial Armageddon just might not have reached us yet.

[edmc id= 3868]Download as pdf[/edmc]

0 Comments