Introduction

From iconic names such as Google, Facebook, Uber and Alibaba to biotech or renewable energy companies, venture capital has funded some of the most prominent companies in today’s economy. Yet, it has also been a center stage for some of the most spectacular crashes such as the bursting of the tech bubble at the beginning of the millennium. This article explores the venture capital industry, giving an insight into its history and detailed technicals diving into startup’s characteristics, investment stages, funding providers and VCs lifecycle. We also provide commentary about the current trends, including the impact of Covid19, and future outlook.

Venture capital defined

Simply put, VC firms comprise minority investors that bet on the future growth of early-stage firms. These are often pre-profit, pre-revenue, and sometimes even pre-product startups. Despite lack of a controlling stake, VCs use their capital, experience, knowledge, and networks to nurture and grow companies. They may invest in specific verticals, technologies, and geographies and often specialize in a particular substage of investment, referred to as early-stage, growth-stage or late-stage VC funding. Although every VC company is unique, few defining attributes apply to most, as detailed below.

How, when, and why did the VC industry emerge

To get the full picture let us go around 200 years back. Before the introduction of shareholders’ limited liability, which took place 1811 in the State of New York, lending money was considered much safer than buying shares and investing in equity was indeed marginal. Even afterwards with reliable information systems available, buying stocks in new ventures remained a privilege for the wealthy. The general public preferred to own shares in existing, listed companies making it difficult for entrepreneurs to advertise their new ventures. The solution to the situation came from the US government during World War II. Although the American military was in desperate need of researchers, it was unable to lure them as they preferred to join academia rather than enroll in the military. The solution in the form of allocating public funds to the best universities in the country was introduced, and elite universities on the East Coast started receiving vast amounts of money dedicated to research related to the military interests.

After the war ended, a new challenge arose: US industry had to convert from manufacturing weapon systems to manufacturing consumer goods. In the meantime, a few wealthy families created their own investment firms trying to take advantage of opportunities created by the end of the wartime economy. Families such as The Whitneys founding J.H. Whitney & Co. and the Rockefellers with Rockefeller Brothers, Inc. took investing in technology companies to the next level and paved the way for development of private equity as an asset class. The firms, rather than acting as co-investors like old-fashioned merchant bankers, began hiring professional management teams that took charge of sourcing opportunities, evaluating risks, and negotiating deals on behalf of their shareholders. Shortly after, in 1946, Georges Doriot, now considered “the father of venture capital”, established the first self-proclaimed venture capital firm: the American Research & Development Corporation (ARD). As a public company, ARD was able to attract institutional investors in private equity for the first time. Unfortunately, the misalignment between shareholders and management resulted in only a few profitable investments for ARD and its shareholders.

Another major turning point was the Small Business Investment Act of 1958, which was part of a response to Soviet Union’s launch of the Sputnik. The act allowed the government to lend money to newly formed investment firms called Small Business Investment Companies (SBIC). Although many of its goals were not achieved, it helped younger management teams to start up their businesses and improved evaluation methods of risks in the technology field, giving rise to legendary venture capitalists like Franklin “Pitch” Johnson. Additionally, a limited partnership legal form was introduced around the same time along with carried interest to incentivize managing partners and thus solve the previously mentioned misalignment problem between shareholders and management. With now less paperwork and better understanding between limited partners and managing partners, venture capital started growing and finally in 1972 Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers – largest and most established venture capital firm – was founded.

Soon afterwards, the Department of Labor introduced new regulation which allowed pension funds to invest directly in venture capital funds, thus opening the doors for significant amounts of new capital. The number of firms increased from just a few dozen at the start of the 1970s to over 650 firms by the end of the 1980s while the capital managed by these firms grew from $3bn to $31bn. However, in the mid 80s returns began to decline and some of the venture firms started facing losses for the first time. It came as a result of increased competition among firms, declining market of initial public offerings and foreign corporations, mainly from Japan and Korea, bringing in capital for early-stage companies. At the time, newly emerging leveraged buyouts attracted billions while venture capital deals were still counted in millions and the growth in the industry remained limited.

Early 1990s brought a change as investors saw companies with huge potential being formed. The well-known giants such as Google, Netscape, Amazon and Yahoo! were all funded by venture capital before any of them turned a profit and IPOs of AOL, Netcom, Spyglass, CompuServe and Amazon among others, generated enormous returns for their venture capital investors. Following these successes, the amount of money committed to the sector climbed from $1.5bn in 1991 to more than $90bn in 2000. Unfortunately, the bursting of the Dot-com bubble in 2000 impacted the entire venture capital industry as valuations for technology startups collapsed causing many venture capital firms to fail.

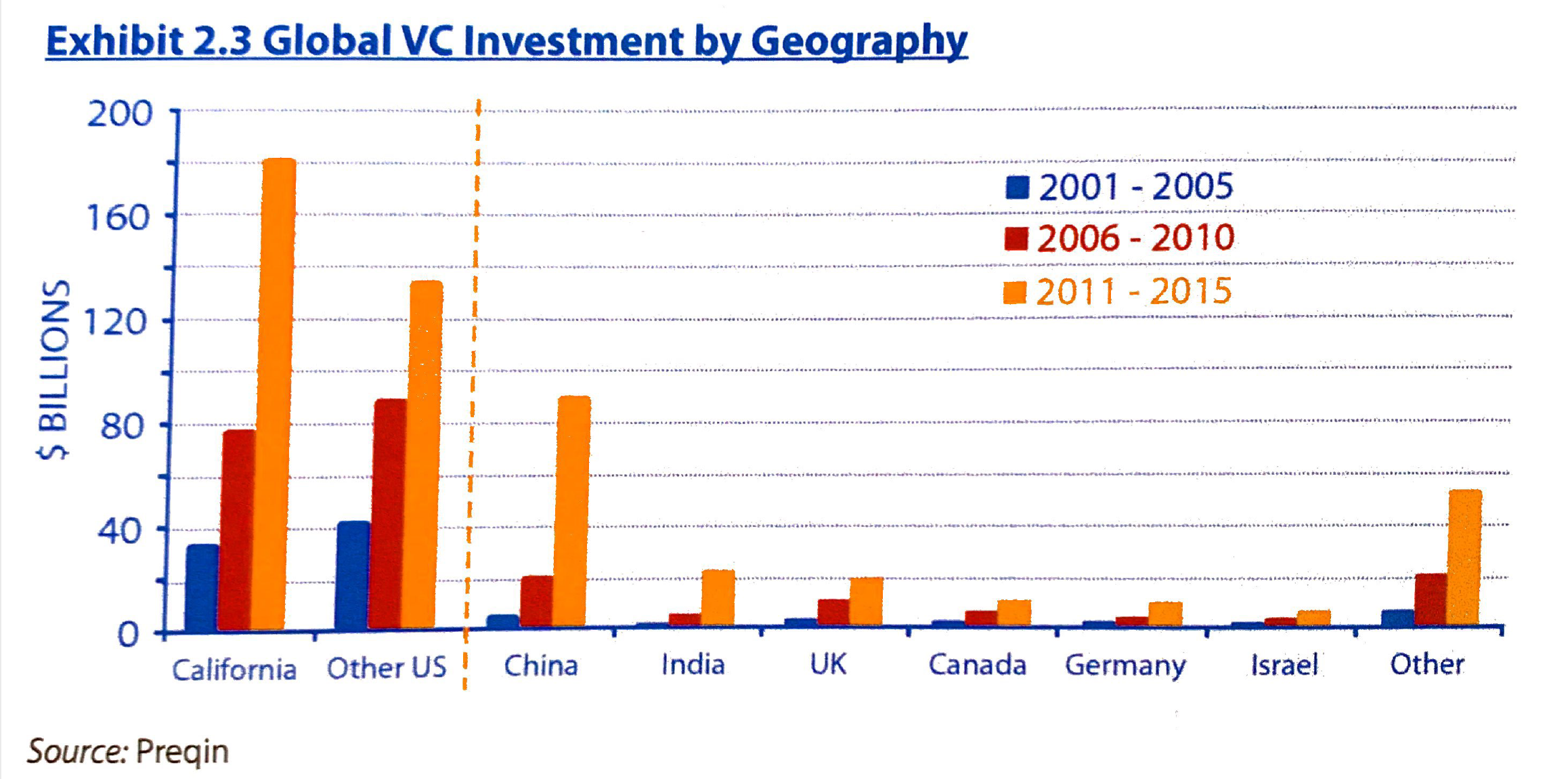

The 21st century saw the global development of venture capital which can be observed on the graph below. The deepest and most developed VC ecosystems can still be found in the US, Silicon Valley in particular, but other parts of the world such as China, India, Europe and Israel have seen active clusters emerging. On the other hand, in the US, part of a growing wave of VC professionals began leaving the congested, costly coasts for quieter, less expensive locations in Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico and North Carolina. This comes as a result of entrepreneurs not being forced to relocate to California or New York to build their businesses as startup ecosystems have experienced a surge in small businesses spread more evenly across the US. Yet, as for now 67% of VC firms are still located in the San Francisco Bay Area, New York and Boston metro areas and cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Washington. These combined hold 85% of US assets under management.

Source: Preqin

However, despite the increase in megadeals in the last five years, the total investment volume has never reached the late 90s/early 2000s peak so far. At the height of the tech bubble at the beginning of the millennium, VC investment in the US amounted to more than $180bn which is twice that of 2017. In fact, at the beginning of 2020 the volume of global VC deals declined by 27% in respect to Q4’19 hitting its lowest point since Q3’13. VC investment in the Americas rose slightly from $33.5bn in Q4’19 to $35.3bn in Q1’20, with the US driving the vast majority of deals. Europe also saw an increase in investment from $7.9bn in Q4’19 to $8.8 billion in Q1’20. However, Asia experienced a 31% decline in funding in the same quarter, dropping from $23.8bn to $16.5bn.

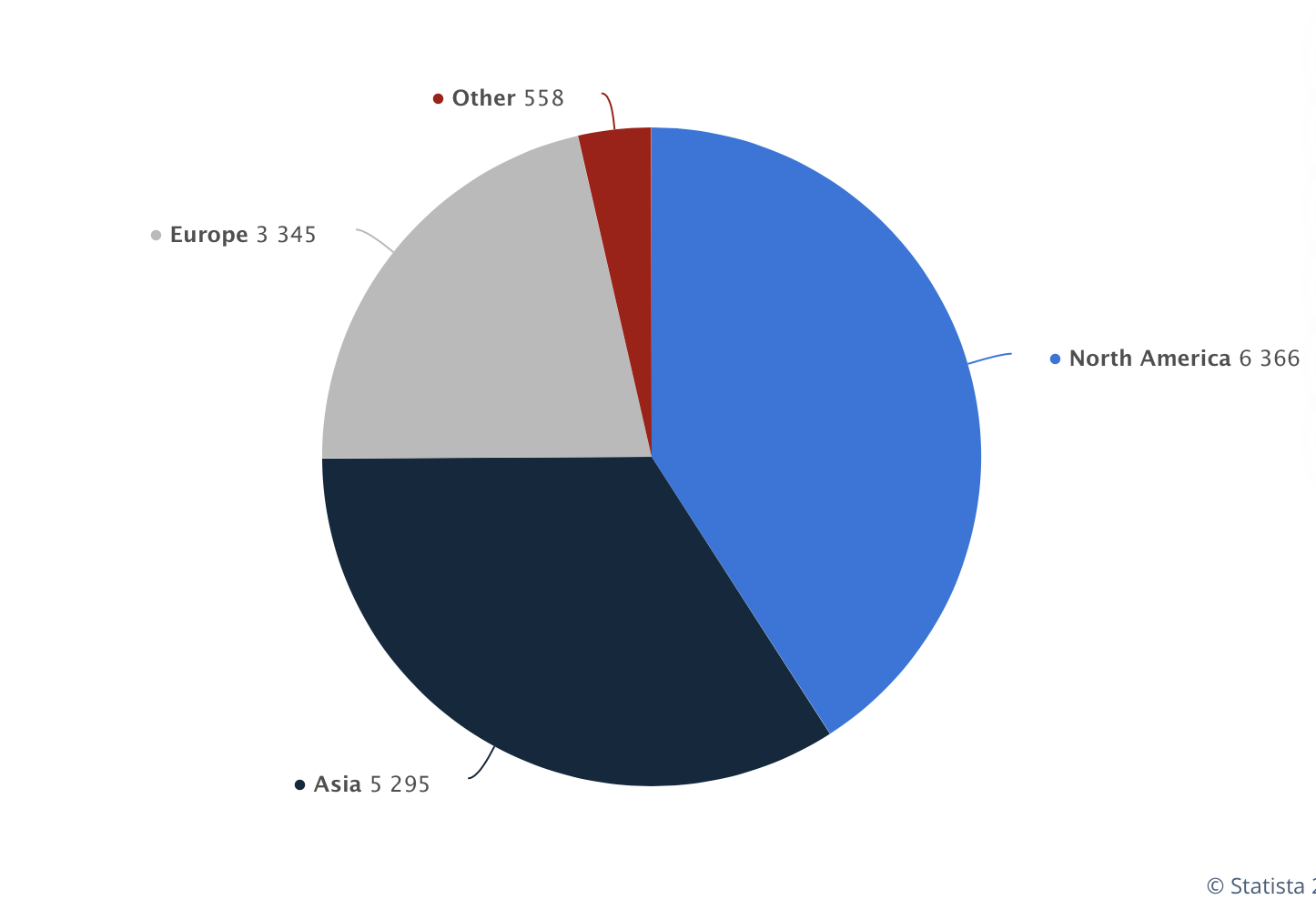

When it comes to the number of venture capital deals worldwide, North America remains the leader, as it can be seen on the graph below representing the number of 2019 deals by region:

Source: Statista

Important startup characteristics

There are various important startup characteristics that a potential investor takes into consideration before investing and, generally speaking, these characteristics can be divided into 2 broad categories:

Qualitative characteristics

1.Team and clients location:

Team location might matter less in the post-pandemic world when most of the tech startups around the world are working remotely, however client location is still very relevant as this characteristic ultimately influences the most important parameters for any investor: exit opportunities and potential exit valuation.

2.Market conditions:

Investors consider both general trends and time-specific particularities. For instance, during the pandemic travel and online education startups obviously experience quite a different outlook from investors, but before Covid a startup in a “hot” industry was much more likely to attract investors and have a higher valuation than a one in a less attractive industry.

3.Competition:

In general, the stronger a startup’s rivals are, the worse it is from the funding raising standpoint (it is hard to build a new social network or browser when Facebook and Google already exist). However, indirect rivals should also be taken into account, as the lack of competition is often a sign of either no need for a product on the market or that the business model (unit economics) does not work.

4.Team composition:

This is simple and understandable – the more relevant experience founders have, the better. VC investors usually prefer to invest in founders with previous startup experience, either as a founder or an employee. One founder is usually considered as a bad sign both in terms of competency (it is highly unlikely that a single person possesses every skill essential to build a successful startup) and risk management (if something happens to the individual founder, the startup is practically over). Hence, VCs prefer startups with 2-3 co-founders who together have all the necessary skills (business sense, coding, sales & marketing etc).

Quantitative characteristics

Market metrics

- TAM (Total Addressable Market): total market demand for a product or service. In other words, it is the aggregate demand in the whole world, without taking any boundaries into consideration.

- TOM (Total Obtainable Market): a special segment within TAM that can be reached by the product or service. For example, geography or price can be the filters that separate TOM from TAM.

- SOM (Serviceable & Obtainable Market): a realistically attainable part of the overall market within reach, i.e. TOM. Meaning that even if the obstacles preventing potential clients from becoming real clients are not too pronounced, they will still most likely stop a portion of the potential clients, and thus differentiate SOM from TOM.

A good example that can help to understand the difference between TAM, TOM and SOM is a so-called “dark kitchen” business. “Dark kitchens” are restaurants working only for delivery, without the option of dining in. The TAM for a “dark kitchen” startup would be the whole market of ready meals worldwide. However, as a new company usually enters the market in a single country and in many cases in a single city, its TOM becomes much smaller (only the ready meals market of the cities it operates in). Furthermore, as it usually starts with a few locations around the city, the “dark kitchen” startup’s SOM narrows down to the districts where the operations already exist.

Unit economics metrics

- Recurring revenue: usually calculated on a monthly (MRR) or an annual (ARR) basis, especially relevant for subscription businesses (eg. SaaS).

- Revenue growth: usually calculated on a month-on-month (MoM) or year-on-year (YoY) basis. Revenue growth is one of the most relevant metrics, as it is what investors primarily seek in startups.

- LTV (Lifetime Value): a characteristic that shows the expected amount of revenue a single customer will generate over the whole period of interaction with the company. Particularly important is its comparison with the CAC metric.

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost): a characteristic that shows how much it costs to attract a single customer and that is calculated by dividing the total amount of money spent on marketing by the number of customers acquired through paid marketing. The ratio LTV/CAC is usually closely looked at by VC investors, and as a rule of thumb 3x is a good result, though it might materially depend on the industry the startup is operating in.

- Retention: a characteristic that shows what is the percentage of customers that stay with the product over time. Retention is usually calculated for cohorts, that is for groups of customers that share some common characteristics (the most widely used is sign-up date).

- Churn: basically a characteristic opposite to retention, that shows what is the percentage of customers that leave the product (might be calculated as 1-Retention).

- Burn: a characteristic that shows how fast the cash is being used. Basically, the amount of cash left divided by the burn rate indicates the number of days/weeks/months left until the cash is depleted, which shows how fast the startup should be raising funds or become profitable in order to survive.

Investment stages

Once the characteristics explained above are analyzed by a VC it is time to invest. In venture capital there are five main stages of investment that differ by the metric numbers required to raise funding.

Funding providers

Stages of investment differ, and so do funding providers in each of them.

When at the pre-seed stage, the startup does not differ materially from simply an idea, the main source of funding is the founders’ own money, FFF (friends, family, and fools), and sometimes angel investors that invest on such an early stage. Accelerators are also available at this stage, with the main goal to help startups grow.

On the seed stage, while there already is a product and first customers, more funding options are available. Venture capital funds start investing at this stage, as well as angel investor syndicates. When the lead angel syndicates the deal, other angels follow if they trust the syndicator. Additionally, it helps angel investors to reduce the risk by diversification as there is no need to invest a large amount of money in a single startup. Lately, equity crowdfunding has become another option to raise a seed round, however a huge list of smaller shareholders can distract professional VCs from investing in later stages.

From Series A onwards, the main investors are VC funds and corporate VC funds, with the latter investing mostly in industries related to the main business of their enterprise.

The term sheet

If a VC fund is ready to invest they send a term sheet to the startup. In the term sheet, specific conditions are usually used as a risk management tool for the VC fund. The most widely used are vesting, liquidation preference, pro rata clause, anti-dilution clause, and drag along and tag along clauses.

1.Vesting:

The process where an employee or founder earns shares over time. This means that founders will not get their shares immediately but according to a predefined schedule which is included in the term sheet. A popular type of vesting is cliff vesting, when a founder first has a period (often 1 year) when if he leaves the company, he would not get any shares, and later a period when shares are accrued in equal proportions for the remaining duration of the vesting. Another type of vesting is accelerated vesting, when the longer a founder stays with the startup, the more substantial the proportion of shares he gets. VC investors apply vesting to reduce the probability of founders leaving the startup early after the investment.

2.Liquidation preference:

A clause fixing how much investors will get before founders get paid in case of an exit or company liquidation. The two important parameters of the liquidation preference are the multiplier and whether the liquidation preference is participating or non-participating. The multiplier is how much of the initial investment investors get back before founders are get paid (1X is the standard, which means that only the sum invested is guaranteed if the exit value outweighs initial investment, though higher multipliers are sometimes used as well), Whether the liquidation preference is participating or non-participating means that, if it is participating, after the initial investment times the multiplier has been paid, investors are still getting some of the money left pro rata with their shares in the company (non-participating is the standard in the industry).

3.Pro rata clause:

An agreement which gives the investor the right (but not the obligation) to participate in one or more future financing rounds to maintain their percentage stake in the company.

4.Anti-dilution clause:

Used to protect previous investors from dilution in down rounds, that is in the rounds where the valuation is lower than the previous one in which the investor participated.

5.Drag along and tag along clauses:

Opposite clauses, both used to protect investors from an unsuccessful, full or partial acquisition by another company. A drag along clause allows a majority shareholder of a company to force the remaining minority shareholders to accept an offer from a third party to purchase the whole company. The majority shareholder who is ‘dragging’ the other shareholders must offer the minority shareholders the same price, terms and conditions that the majority shareholder has been offered. Conversely, when a majority shareholder sells their shares, a tag along right will entitle the minority shareholder to participate in the sale at the same time for the same price for the shares. The minority shareholder then ‘tags along’ with the majority shareholder’s sale.

VC fund life cycle

Stage A: Development Fund Concept

The first stage of the life cycle of a VC fund is raising capital. This requires roadshows with potential investors and the communication of a fund’s proposed minimum assets under management (AUM), investment strategy, industry focus, ticket size, and fee structure. In particular, at the start of the fundraising process, most funds assign a minimum threshold of capital that they have to raise for the fund to be viable. If this threshold is not met, the fundraising process is aborted. On the other hand, if the fund is successfully raised, most fund managers ask their LPs for a first call of capital, which is usually around 40% of the total capital committed. The remaining capital is called by the fund whenever it needs to make more investments. It should also be noted that even if this threshold is reached, most VCs spend over a year afterwards continuing to fundraise to raise the largest fund possible. After all, the bigger the fund, the greater the management fees and the larger the potential carry.

What makes this part tricky, especially for first time GPs, is that most LPs prefer to invest in funds that have a pipeline of potential investments lined up. What this means is that GPs have to be engaging with startups and negotiating potential deals while raising money at the same time. Such a process can be extremely difficult for GPs, as investment targets may not consider them credible enough without a fully raised fund. In addition, if a GP promises financing to a startup but is unable to raise the fund in time, it can suffer significant reputational damage.

Stage B: Investment Execution

The first part of the execution process for deals in the VC space is origination. Deals can be originated through a VC’s network, various startup-oriented events, or cold calling/pitching by startups.

What follows is business plan analysis and operational/financial due diligence. This usually requires the startup to provide significant information regarding its historical financials, growth projections, operation model, and management team.

Afterwards, if a VC would like to invest in a startup, it sends a term sheet to the company. An important consideration is that a term sheet is non-binding and a VC could drop out of the deal at any point. That being said, it can still have several procedural promises on the part of the startup. This can include confidentiality of the terms of the term sheet or no shop clauses, which prevent the startup from seeking funding from other investors for a period of time.

After a term sheet has been sent and negotiated, a VC moves into the legal due-diligence phase. This includes validating the accuracy of all the claims and disclosures made by the company during the business due-diligence phase. For example, if a company claims to be the first to develop a certain type of technology, this phase will allow the VC to check whether the company actually has a patent for the technology and how long it will last. This process also allows for the correction of a number of legal details such as the reporting of financials, cap tables, and vesting schedules.

Finally, if both parties agree to the terms and the legal due-diligence goes smoothly, a deal is closed. The structure of this entire process can be very flexible, with some VCs preferring to conduct both business and legal due-diligence before a term-sheet is drafted, while others preferring to only do business due-diligence before this stage.

In terms of the valuation of target companies, there exists a range of different methods that can theoretically be used to come up with a valuation. That being said, in practice, it is the three main valuation methods that are most often used across the spectrum of stages for VC investments.

For early stage to growth stage companies, public comps and precedent transactions are the most used valuation methods. This is inevitably because when a company is so small and is growing at such high rates, it can be impossible to accurately estimate its future cash flows. Thus, comparing multiples like EV/revenue and EV/EBITDA (assuming EBITDA is positive) with a peer group is far more practical. In particular, conducting a precedent transactions analysis of multiples paid during funding rounds of similar companies is a method that VCs specifically focus on. It should also be noted that the range of multiples used is not limited to revenue or EBITDA based multiples, as you often pair a company’s EV with an operating metric or an industry-specific financial metric. For example, for companies focused on mobile applications, you may use EV/Users, EV/Average Revenue per user, EV/Downloads. For SaaS companies, you may use EV/Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) or EV/Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR). For e-commerce companies, you may use EV/Gross Merchandise Value (GMV).

For late stage companies, many VCs use traditional DCFs in addition to market based multiples. After all, it is much easier to accurately project a company’s free cash flow once it matures and starts growing at slower rates. For seed rounds, on the other hand, most investments are done using convertible notes specifically because it is hard to come up with a reasonable valuation, especially when a company’s product and business model is not fully fleshed out. These convertible notes are then usually converted to equity in a company’s series A financing based on the valuation of the round.

Stage C: Investment Monitoring and VC’s “Value Add”

This stage can be either passive or active, depending on the strategy of the VC. For more passive funds, GPs usually have minimal contact with portfolio companies post-investment, with the extent of their involvement limited to attending company board meetings. More active funds, on the other hand, are far more likely to engage with portfolio companies. This includes, but is not limited to, the following activities:

- Marketing the company to other investors and leading/contributing to new rounds of financing

- Aiding the firm with recruitment of key hires, especially for management positions

- Strategic planning and optimization of operations

One interesting trend within this stage is that most VCs are now trying exceptionally hard to play an active role in the value creation process of portfolio companies. This is because, given the consistently large inflows into the VC asset class over the past decade, many VC financing markets have become overcrowded, especially in hubs like San Francisco or Singapore. This has led to a shift in the power dynamic between VCs and targets, as startups now have a surplus of VCs to choose from. Thus, it is no longer enough to bring money to the table, as startups want to partner with VCs that have deep industry experience and a strong base of connections which they can leverage.

Stage D: Exits and Distributions of Cash

Hopefully, by the end of a fund’s life, the company will have exited from its positions so it can distribute cash to investors. The most common exits are inevitably through IPOs or acquisitions by strategic players/PE funds. Most of the time, an acquisition/trade sale is preferred to an IPO. From a cost perspective, the underwriting and advisory costs associated with an IPO are much higher than a trade sale. IPOs also introduce significant price uncertainty, as it is only on the last day of a 6-month IPO process when you know what price a company will go public at. With a trade sale, a company has the ability to not just have price visibility from day one, but also play an active role in negotiating this price. IPOs also come with a significant lockup period (6 months in the US), with large investors exposed to significant price risk in that time. In terms of valuations, historically IPOs have provided companies with higher valuation multiples. Nonetheless, with corporate cash and PE dry powder currently at all time highs, it is likely that valuations could go either way.

That being said, oftentimes a fund can approach the end of its life but the assets in its portfolio may not be ready to exit yet. Further compounding this problem is the fact that the VC strategy usually entails taking minority positions in a number of firms. What this means is that, unlike a PE firm which holds a majority stake in its portfolio companies, a single VC cannot force a sale/IPO of a portfolio company just because it needs to liquidate its fund. This has, in recent years, led to immense growth in the VC secondary market. A very common GP-led secondary transaction occurs when a fund has reached the end of its life but several assets are not ready for exit. In this scenario, a GP gives the LPs the option to roll over these existing assets into a new fund vehicle and effectively extend the life of the fund, or sell their interests in the fund to a secondary buyer.

As the fund exits from its positions, it begins to distribute the proceeds to its investor base. These proceeds can be in the form of cash or stock. Distribution of stock occurs when a company exits via an IPO or an M&A where part of the purchase consideration includes the buyer’s stock. Assuming a 2/20 compensation structure (annual management fees = 2% of AUM, carried interest = 20% of profits), most of the time a fund needs to reach a specific hurdle rate (usually around 6% – 8%) before it can start receiving its 20% carried interest.

Future outlook and trends

The Covid-19 pandemic has proved to be an exciting yet challenging time for VC around the world, separating the good from the mediocre funds. Even though the global pandemic has not seemed to lower investors’ optimism, with VCs continuing to raise large funds and deploying capital into the Covid induced digital transformation, it poses a number of threats to be faced by venture investors.

The main challenge has been increased deal competition due to a smaller number of Covid resilient companies. Many prominent upstarts, especially in the travel and leisure vertical, have failed to endure widespread “stay at home” regulation and will have to be written down by investors. On the other hand, digital first companies are experiencing a vast increase in demand from customers and thus skyrocketing valuations. This creates a fierce battleground for funds who, having raised capital, are looking to invest in a limited pool of expensive companies.

VC which tended to rely on local networks of contact and regional expertise became a more global playing field, where investors from all over the world can get onto a Zoom call with a founder no matter the location. Local VCs are being crowded out by well-known mega funds, such as Sequoia and Andreessen Horowitz, on their own turf. Additionally, the lack of face-to-face due diligence often leads to increased investment uncertainty. Investors often have to back founders based on outdated metrics that struggle to quantify the impact of Covid and gauge a startup’s true performance, as in many cases growth and traction have stalled since the beginning of the pandemic.

This sudden change of circumstances is likely to negatively impact the performance of new VCs more, rather than established players. A 2017 study by the European Investment Fund analysed data from two decades of European VC activity and found that experience is a key determinant in portfolio performance during market downturns. One reason for established players outperforming first-timers is that during times of economic uncertainty, they are likely to benefit from the flight to quality, with both investors and startups willing to rely more on experienced professionals over newcomers.

Another reason behind the outperformance of VCs with a few funds already on their record is that first time VCs are reluctant to cut out dying companies. This is because, worried about their reputation, they cannot afford bad news for their first fund as they will be less likely to raise the second. Experienced funds know when they must cut their losses, while inexperienced ones, using bridge rounds and emergency financing, tend to needlessly prop up ventures they should allow to fold.

However, the pandemic has opened a vast array of opportunities especially for the younger funds, which tend to be more agile. As digital technology is forced to accelerate exponentially, new players focused on this vertical can capitalise on this trend, as much as experienced funds.

Besides the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic, there are other pronounced trends, the main being shifting investment principles and increased importance of AI in the VC method, that have been and will continue to shape the industry.

As investors are increasingly looking for their capital to not only generate returns but also to create a positive social impact, VCs will have to look for purpose beyond solely growth and profit. With portfolios aligned with ESG – Environmental, Social and Governance – principles recently outperforming regular portfolios both in terms of capital inflows as well as return on investment, VC funds will have to evaluate their investments accordingly in order to meet growing investor demand for such assets. In the past, VCs typically targeted disruptive business models that often do not incorporate ESG models in their operations as tech firms tend to have low direct impact on the environment. However, as these companies grow they are likely to be faced with ESG challenges, which they might fail to address in pursuit of exponential growth. A widespread ethical concern for tech companies is their approach to personal data, something that will remain in the spotlight of regulators and will carry risks which can be mitigated by incorporating ESG practices. The adoption of ESG principles in the VC investment method will help founders integrate them into the firm’s operations early on and provide a healthy framework for future operations, thus attracting the increasing number of socially conscious investors.

One of the most noticeable industry trends in the past decade have been developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) that transformed how businesses operate, and VC is no different. ML is increasingly being utilised in the VC investment method as it allows to process thousands of data points and determine a target company’s viability. The VC space can largely benefit from AI in terms of deal sourcing, due diligence, assessing the founders personality and grant the necessary analytical prowess to disburse their capital in the most profitable manner. Startups themselves have become increasingly data driven and focused on utilising their vast amounts of information to improve their operations and grow faster, which is increasingly becoming a requirement for venture funding. AI companies have attracted the highest number of venture capital investors in 2019 while big data and internet of things led in terms of investor-to-idea ratio (number of venture capital investors / number of funded companies) and average deal size. AI and ML incorporation in startups and in the investment process is particularly attractive for VCs as it allows them to automate processes and lower cost without the expense of growth, precisely what VCs are looking for when investing.

0 Comments