Introduction

February 26th 2007 marked one of the peaks of the pre-financial crisis exuberance: KKR [NYSE: KKR] and TPG [NASDAQ: TPG], together with a number of banks including Goldman Sachs [NYSE: GS] and Lehman Brothers, announced the acquisition of the Texas power company TXU for an astounding $44.3bn in Enterprise Value, the largest LBO in history at the time. Soon, however, this transaction came back to haunt the financial sponsors: instead of the steady cash flows that you might expect from a utility, TXU saw its revenues fall in the following years, as the advent of fracking led to lower energy prices in the unregulated Texas energy market. Despite keeping up with interest payments, the debt load was far too large for TXU to be able to repay the principle, leading to its bankruptcy in 2014. In this article, we will try to understand what it was that made the sponsors eager to do this deal, why the deal ultimately failed, and what learnings can be derived from the deal’s underwhelming outcome.

Background

At the time of the buyout, TXU was one of the most profitable utilities in the US and the largest coal power plant operator in Texas, serving 3 million retail utility customers. The century old Dallas-based energy company managed a portfolio of both competitive and regulated energy businesses primarily in Texas.

TXU’s subsidiaries fell under the TXU Energy Holdings segment, a holding company which included TXU Energy, TXU Power, TXU Wholesale, and TXU DevCo. Despite operating as a single integrated business, the four distinct legal entities were established to facilitate operational, accounting and performance management functions. TXU Energy provided electricity and other services to 2.1m customers in Texas. At the time, TXU Energy’s share of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) retail residential and small business markets was 37% and 26% respectively. The ERCOT region accounted for around 85% of electricity consumption in Texas and was TXU’s main operating geography. TXU Power possessed a total generation capacity of 18,100 MW in Texas, including 9,500 MW from natural gas power plants, 5,800 MW from coal-powered facilities and 2,300 MW of nuclear generation. TXU Power’s fleet of 19 plants consisted of 14 natural gas power plants, 4 lignite/coal power plants, and one nuclear power plant. TXU Wholesale provided wholesale energy sales and purchases and stood as the largest purchaser of wind-generated electricity in Texas at the time. TXU DevCo was established to develop new lignite/coal-fuelled generation facilities. The combined TXU Energy Holdings business also engaged in commodity risk management and trading activities. TXU’s regulated business, TXU Electric Delivery, operated the largest distribution and transmission system in Texas, powering 3m delivery points with over 110,000 miles of distribution.

The events leading up to the deal began in 2006, when regulators in Texas were worried about a lack of supply in the state’s grid. In the same year, TXU announced its intention to construct 11 lignite/coal-fuelled generation units in Texas, with a combined estimated capacity of up to 9,300 MW. This would make the firm one of the largest carbon emitters in the US. This decision drew significant attention from environmental advocacy groups, with TXU and its CEO at the time, John Wilder, coming under the scrutiny of their concerns and criticisms. Not only were environmentalists opposed to the plans, but even regulators and some investors were worried about the environmental impact of the plants and the financial risks brought about by such a significant capital expenditure. In addition to scrutiny over environmental concerns, Wilder angered both legislators and consumers when TXU kept electricity prices unjustifiably elevated after hurricanes had led to what should have been a temporary spike in prices.

On February 26th, 2007, the consortium of firms led by TPG and KKR announced their intentions to take TXU private. The deal was contingent on the commitment to address environmental concerns, and agreements were later made to reduce the number of new coal facilities from 11 to 3 plants. In addition to scaling back the construction of coal-fired power plants, the proposed buyout included plans to cut TXU’s carbon emissions and double spending to promote energy efficiency. These concessions were seen as a key driving force to attempt to conciliate environmental concerns and secure regulatory approval. This proved to work, as by the time the deal was first announced it had already been endorsed by two environmental groups: Environmental Defense and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Due to TXU being an essential utility firm and a key part of Texas’ infrastructure network, the sponsors had to charm legislators. Both KKR and TPG had failed to acquire utility companies Unisource (Arizona) and Portland General (Oregon) respectively in the early 2000’s after being blocked by regulators, further fuelling their determination to get this deal through. According to Texans for Public Justice, an advocacy group, the buyers spent a total of around $17m in attempt to win over legislatures and prevent the deal from being vetoed. This included $11m on advertising, $6m on lobbyists, and $180,000 to entertain lawmakers and their staffs. Consumers, however, were mainly concerned with the substantial cost of debt brought about by the deal impacting residential electricity prices. The sponsors, therefore, included terms in the deal to reduce electricity prices by 10% for residential customers not already enrolled in low-price plans. These price protections, which were promised out until September 2008, were meant to result in $300m of annual savings. As will be seen later on, however, consumers didn’t experience the burden of higher prices as increased competition and falling demand depressed prices on their own.

The $44.3bn deal between TXU and the financial sponsors offered shareholders $69.25 in cash per share at closing, representing a 25% premium over the average of the 20 days leading up to the announcement of the deal. This represented an EV/EBITDA multiple of 8.5x. This stood higher than the utility industry average of 7.9x at the time. It was also on the lower side of an in-depth valuation done by Morgan Stanley and Blackstone around the same time, which valued the firm 8-13x EV/EBITDA. Citigroup [NYSE: C], Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan [NYSE: JPM], Lehman Brothers and Morgan Stanley [NYSE: MS], all committed LBO financing towards the deal at the proposal date. The takeover was financed by a $24.5bn senior secured bank loan and $11.25bn of senior unsecured bridge loans. In total, the sponsors paid over $8bn in cash and $36bn in debt. TXU, renamed Energy Future Holdings, was advised by both Credit Suisse and Lazard [NYSE: LAZ] on the deal. In addition to the aforementioned price cuts and environmental terms, the merger plan included the reorganization of the group into three separate and distinct companies: Luminant Energy, which wass focused on generation, Oncor Electric Delivery, a transmission and distribution company (previously TXU Electric Delivery) and finally TXU Energy, which retained its name and operations as the retail business.

Investment Rationale

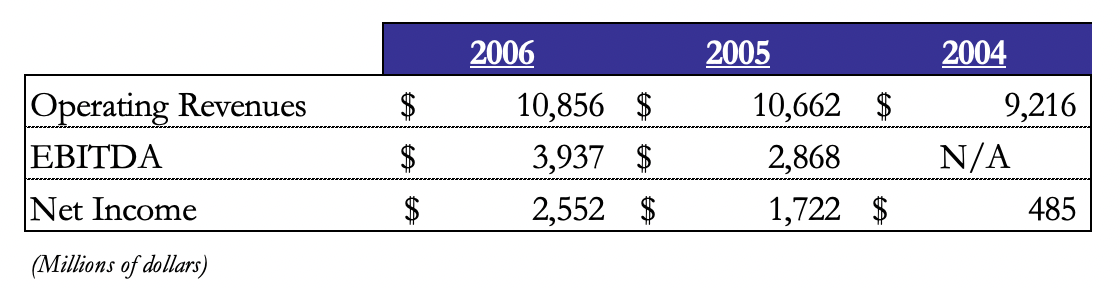

Source: Company’s Financials, Bocconi Students Investment Club

In 2007, buying out TXU may have looked like a great investment. The firm was the fifth largest energy company in the US and one of the largest electricity providers in Texas. With natural gas prices close to their peak, the firm enjoyed large margins on the energy produced by their nuclear and coal-power generation facilities. Furthermore, 5-years prior to the deal, Texas deregulated its electricity market, opening it up to competition. Prior to deregulation, TXU held a monopoly in Texas, particularly in the Northern part of the state. The vast network of infrastructure the utility firm possessed provided steady foreseeable revenues, even when faced with competition from other firms. Furthermore, the deregulated and expansive Texan energy market provided the buyers with visions for future growth of the acquired firm. Moreover, the steady cashflows provided by utility companies generally make them attractive investments. At the time of the deal TXU was posting strong financials, with a net EBITDA of nearly $4.0bn in 2006 according to the group’s financial statements.

One of the key motivations for acquiring TXU was the expected increase in natural gas prices. This assumption is ultimately what led to the firm’s downfall. The sponsors had a strong belief that the high natural gas prices mentioned previously would persist in the future, with the consensus at the time being that the demand for energy was expected to exceed generation capacity. This would have proven to be especially fruitful for TXU, which was heavily exposed to coal and nuclear generation. Since electricity prices tended to correlate with natural gas prices, the grid’s electricity prices were expected to continue increasing, inflating TXU’s margins on their electricity generation from coal and nuclear plants.

Alongside this play on future commodity prices, the sponsors saw an opportunity to easily gain support by pledging to solve the firms environmental and customer concerns. This included appointing figures like William Reilly, Chairman Emeritus of the World Wildlife Fund, to the board of directors, and the other climate commitments discussed previously.

The Road to Bankruptcy

As EFH’s outlook was worsening by the day, it entered a restructuring phase. This plan split into three divisions: Luminant, its merchant power unit, TXU Energy, its retail electric unit, and Oncor’s, its power delivery business. Consequently, lenders’ worries increased, and banks attempted to renegotiate terms as they wanted investors to “share the pain”. However, disputes arose as senior KKR deal makers refused and JP Morgan’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, described it as a “one-way relationship”.

By early 2009, EFH had barely enough operating profit to cover $3bn in annual interest payments and the repayment of its $22bn debt maturing in 2014 was unthinkable. Carl Blake, analyst at Gimme Credit, stated at the time that “EFH’s capital structure is untenable.” Clearly, EFH’s poor ability to produce earnings was not in line with its burdensome balance sheet obligations. As a result, in August 2009, Moody’s downgraded its credit rating from B3 to Caa1. Furthermore, after a goodwill write off, the book value of the company was now worth a negative $3.2bn and, subsequently, KKR wrote its initial $366m equity investment down by 50%.

EFH’s initial operational struggles were due to the 2008 recession, which led to a 7.6% fall in energy consumption in Texas. Thus, one of the key investment rationales, steadily increasing energy demand, turned out not to be true. Subsequently, H1 revenues in 2009 were down 15% YoY, and this negative shock further reduced the probability of meeting obligation payments. Therefore, EFH started to exercise PIK toggle, a financial engineering technique consisting in paying debt by taking on more of it, here $250m, rather than in cash. However, EFH still had $3.9bn in cash and untapped borrowings, which would be sufficient to survive the next couple of years. A feasible solution at that point was to sell power plants in a search for opportunities to deleverage. Possible bidders were Houston power producer Calpine or NRG, but talks did not prove successful. Ironically, while navigating through this storm for EFH, the invested PE firms were still making incredibly high fees: KKR, Goldman Sachs, and TPG, split $300m in fees for the brainwork behind the takeover.

By fall 2009, EFH had already paid financial sponsors $370m in management fees, hence a discussed option was for the sponsors to inject additional equity. In addition, EFH asked its bondholders, whose bonds were trading at steep discounts, to consider swapping some of their loans and bonds for new ones. This meant losing 25-50% of the value and thus, few investors accepted the offer. In 2010, EFH raised $3.5bn to pay down old debt and hopes was starting to arise. Indeed hedges were in places to protect from declines in gas prices, cash on hand, new plants promised additional future capacity, and the big tower of debt wouldn’t come until 2014, until which natural gas prices could always rise. However, prices wouldn’t bulge, and in January 2010, the price in North Texas was around $40, versus the mid-$60s per megawatt per hour expectations in the investment’s “original thesis”. This marked another failure in the financial sponsors’ rationale, and with gas prices so far off, they were only left to accept that they wouldn’t make anything close to the hoped returns on their EFH bet.

In 2012, America’s most famous investor, Warren Buffet, highlighted in his annual shareholder letter that his $2bn investment in EFH bonds was a “big mistake” and that it was at risk of losing all its value. This was only a mere reminder to EFH’s owners of how bad things were going. Indeed, in 2011 the company reported a $1.9bn loss amid record low natural gas prices. Notably, a reason for plummeting prices of natural gas was the sharp rise in domestic natural gas exploration, as a result of the new fracking process. All things equal, the resulting higher gas supply drove prices down. In addition, EFH’s retail business lost about 17% of its customers to cheaper rivals. This significantly worsened EFH’s financial performance and dramatically dragged it down in its race to pay off $35bn in debt by 2014. Ultimately, EFH’s management, alongside the sponsors, was not able to turn this negative spiral around and was forced to file for bankruptcy in April 2014.

What can we learn?

A first key lesson from the TXU investment is that it is not wise, as a financial sponsor, to expose yourself to commodity prices. They are notoriously hard to predict and very cyclical. If you pair this cyclicality with a highly levered capital structure, a bust in commodity prices can soon lead to bankruptcy (if you are selling commodities), as was the case for TXU. At the time of investing, the investment rationale behind buying TXU felt strong: gas and oil prices had historically been linked. Given that oil prices ‘would only continue to rise’ (according to the ‘peak oil’ theory, which was very popular at the time of the LBO), gas prices should also increase. This would increase the price of energy derived from burning gas, which would then boost TXU’s EBITDA, as it produced a large part of its energy using coal power plants. However, as we all know, the exact opposite happened. Energy prices in Texas fell by 7.6% in 2008 and continued this decline in the following years, largely driven by the fact that gas prices reached record lows in 2011, which led to sharp falls in TXU’s EBITDA. In defence of the financial sponsors, one could argue that they could not have necessarily predicted that fracking would lead to such a large increase in gas supply. On the other hand, we feel that the historic volatility of commodity prices implies that it is best to stay away from doing LBOs of commodity vendors.

The next learning pertains to leverage. When credit markets are willing to finance pretty much everything, it is of course tempting for a financial sponsor to do big deals. However, in moments where one can borrow as much as one wants, one should probably remember what that has historically meant. If we look at history, banks were always most willing to underwrite gigantic transactions at the top of economic booms, which were soon followed by recessions (e.g., RJR Nabisco in 1989). Therefore, an extreme willingness of banks to finance deals could suggest that one is at the market top, meaning that the amount of leverage that one can take on will likely exceed what is viable in the coming worsening economic environment. Thus, even though it is hard to stick to that rule, when banks are too eager to lend you money for buyouts, you should probably not do as many deals, or at least not borrow as much as the banks want to lend you. In the case of TXU, the issue of slowing revenues was compounded by an overlevered capital structure.

Finally, we can learn from the TXU deal that just because a similar deal worked in the past, it does not mean that it will work in the future. In 2004, TPG and KKR were part of the consortium that purchased Texas Genco, the then second-largest power generator in the state for $3.7bn. Just two years later, they sold the business to NRG Energy for $5.8bn, likely more than doubling their equity. It was easy to think that because this investment in a power generation company worked well, the next one would as well. After all, isn’t investing all about pattern recognition? Whilst this is true, we argue that this pertains more to the circumstances of the deal rather than the specific companies. In 2004, the US was emerging from a recession, meaning energy prices were rising, whilst the exact opposite was the case in 2007. Therefore, it is essential to not simply repeat the same deal in a different time, as the circumstances likely have changed. Rather, the key is to repeat a deal with similar circumstances that is not necessarily in the same industry.

Conclusion

The TXU story, despite ending in an unpleasant way for the investors, provides us with multiple important learnings, including the importance of staying away from cyclical industries, not overleveraging yourself, and remembering that just because a certain type of company peformed well in the past, it does not guarantee that the same will be true for a new investment in a similar company. It is likely that the investors that underwrote the TXU acquisition knew the aforementioned learnings; after all, they were experienced investors at some of the most respected firms in the industry. Therefore, the real challenge is remembering these learnings when faced with the opportunity to do a large deal, which brings with it a certain amount of prestige, and when the environment feels as though everything can only go well. Today, financial markets are somewhat constrained, meaning the risk of ignoring prior learnings is smaller. When, however, the next bubble inevitably comes around, it will be essential for investors to remember these learnings.

1 Comment

Maavo Sri · 4 August 2024 at 7:12

It is a great article. I loved reading it