In the last article[1], we explained the three arrows (measures) of Abenomics stimulus. In this article instead we will take a look at the most recent data about the Japanese economy and then focus on the structural reforms. In particular, reforms that are supposed to tackle the labour market and secure the growth of Japanese economy in the long-run.

GDP & Inflation

On Monday (15th February 2016) GDP growth data was published and it represents (another) blow to Shinzo Abe and his Abenomics stimulus. In fact, Japan’s economy shrank at an annualized rate of 1.4 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2015, below expectations of -1.2%. This contraction was again driven by a sharp decline in consumption (-0.8%), showing the fragility of Abenomics approach and seriously damaging Shinzo Abe and Haruhiko Kuroda’s (Governor of the Bank of Japan) credibility.

Headline consumer prices rose at an annual pace of 0.2 per cent in December, in line with expectations, but down from November’s 0.3 per cent advance. So-called “core-core” inflation, the BoJ’s preferred measure that excludes both food and energy prices, rose by 0.8 per cent year-on-year in December, slower than the 0.9 per cent pace in November.

Labour Market

Japanese labour market, at a first glance, might appear to be in excellent conditions; in fact, as a matter of fact, it is hard to find an economy with a lower unemployment rate than that of Japan (3.3%). Furthermore, since the start of Abenomics in December 2012, 1.82 million jobs have been added. A reasonable question therefore arises: “What is wrong with the labor market?”

The answer is: Aging population.

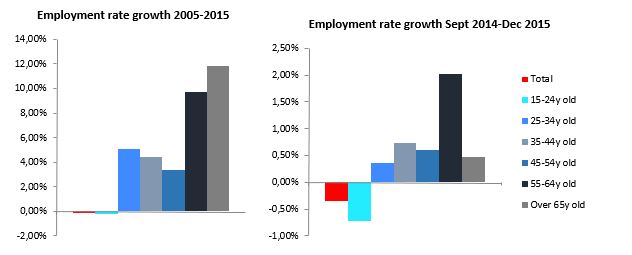

As we can see from the graph above, people over 65 years old, along with those in between 55 and 64 years old, were the ones experiencing the biggest proportional increase in employment rate from the 2005 and 2015, respectively by 11.86% and 9.72%.

More than half of the new jobs, which have been created since December 2012, have been filled by people older than 65 who often work to stay active and supplement inadequate incomes – also, the great majority of the new jobs are part time.

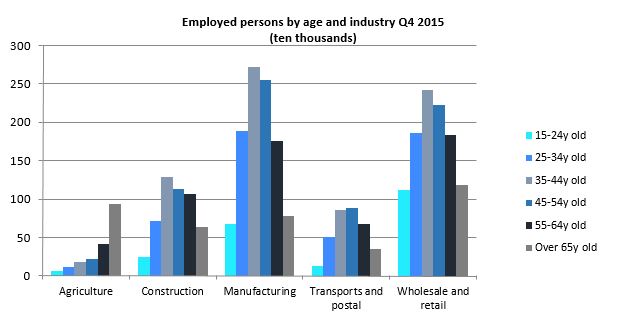

As the figures below show, as of the last quarter of 2015, people over 65 years of age are the most represented category among the agricultural workforce. This data is partially worrying as agriculture in itself is an activity requiring strength and energy and therefore productivity is strongly inversely related to age; however due to the fact that most farms are family-managed, it is also the sector where the passage from being out of the labour force to being employed is easier for the older members of the family. Japanese agriculture contributes only by almost 2% to the national GDP, partially because of the lack of arable land (only 20% of Japan can be cultivated) but also because of the lack of competition in the sector, characterized by cooperatives and high protectionism. The full potential of agriculture is therefore not currently exploited and a deep restructuring of its organization and workforce would be beneficial.

What is the solution?

A relocation of the different age segments of the population to their most suitable sectors, in order to maximize the overall productivity (this is of course possible and not extremely costly for jobs not requiring highly specialized skills) would lead to a genuine increase in wages backed by enhanced productivity, which might be exactly the positive boost to inflation Abe and Kuroda are so desperately looking for. This could only be achieved through a system of incentives within a wider reform of the labour market.

Currently Shinzo Abe and his government have started to tackle the labour market through “Womenomics”, a women-friendly policy that includes measures ranging from efforts to expand childcare places to creating a scheme of rewards for companies that provide a more welcoming workplace for women.

Another measure often neglected but at least as equally important as “Womenomics” relates to changes in immigration laws making them more favourable for skilled foreign workers.

Currently the most part of immigration comes from Brazil and Philippines, which both show GINI coefficients higher than that of Japan and, in accordance with economic theory, supply the country with workers laying in the lower tail of their local skill distribution.

This reform should therefore try to divert the sources of immigrants to other countries showing lower inequality and thus resulting in a positive influx of skilled migrants, able to take the place of an increasingly aging population. However, the issue is not just economic but also political.

This reform has often been contrasted by the most part of Japanese asserting that immigrants would alter significantly Japan’s homogeneous population with its shared values and harmonious consensus, in the same way as Nikkeijin (Brazilian immigrants of Japanese origins) do.

Lining up with people’s sentiment, the country’s minister for the empowerment of women describes immigration measures as “Pandora’s box.” However, if Japan succeeds in attracting foreign skilled workers, the reform might act actually as a complement to “Womenomics” placing women in highly automatized sectors and skilled immigrants in sectors most affected by the overall aging. As the time passes, consequently, it seems that foreign workers are the missing factor that would accelerate the economy and bring inflation and growth to desirable levels.

Is it time to open the Pandora’s Box?

Monetary stimulus has been the mostly used measure of Abenomics, but it has not improved the economy in the way that policy makers and central bankers expected.

The BoJ intervention from December and January did not cause a further depreciation of Yen due to the global turmoil in the financial markets which raised demand for safe havens. In fact, Yen is on the highest level recorded in 16 months, trading at around 112-114 per Dollar. The figures put pressure on the Bank of Japan for even more monetary stimulus to encourage a strong round of wage rises this spring.

Although Kuroda denies that, there is a growing number of market participants who believe that liquidity in the fixed income market is drying up. In fact, the last two interventions of the Bank of Japan) are perceived, among certain economists, as the BoJ is avoiding to expand the current level of QQE.

In any case, monetary stimulus is not sustainable and cannot drive the economic growth in the medium and long run. Hereinafter, structural reforms are needed. Considering that Japanese general elections are approaching (they should take place by December 2018) and that Abenomics policy has not yet achieved any significant success, structural reforms should be implemented now or never. Reforms operate with a wider time lag than monetary policy and if Abe wants the Japanese population to see the results before voting, he will have to implement them really soon.

[1] published on the 7th of November

[edmc id= 3441]Download as PDF[/edmc]

0 Comments