Introduction

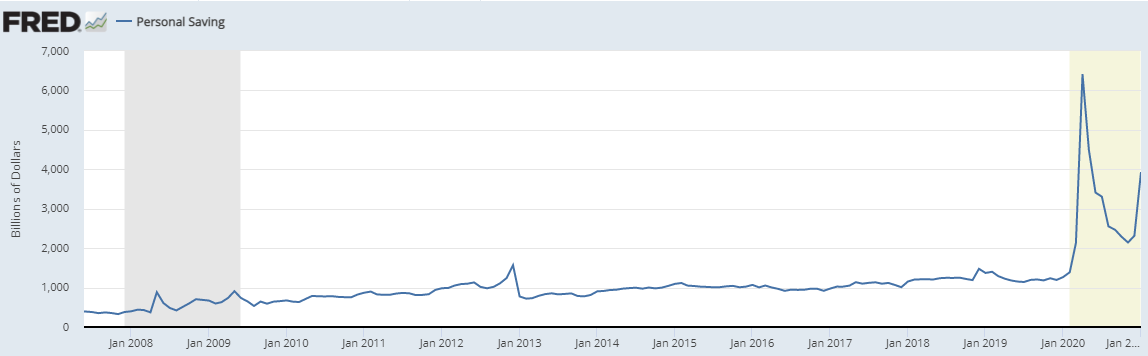

A specter is in the horizon for US investors: the specter of inflation. As the fed policy objectives shifted toward allowing a brief term inflation “overshoot” the 10-year and 5-year breakeven inflation rates, the differential between TIPS and nominal bond yields, have reached new heights in the last few months, with the 5-year breakeven rate in particular reaching levels not seen since the great financial crisis. Breakeven inflation rates do not necessarily reflect the market expectation of inflation, they include an inflation risk premium, which is likely itself to vary overtime and may push breakeven rates above or below “real” expected inflation rates, but the recent increase is still very much notable.

Source: FRED

Most pundits have given 2 main interpretations to this event:

- That the expected inflationary effect will be temporary and caused by the quick recovery of the economy, that the Fed won’t have any issues in controlling the phenomenon

- That inflation won’t be effectively controlled by the Fed and might even result in a resurgence of 1970’s style super-inflation or force a strong tightening of monetary policy

In this article we will analyze these two points of view, as well as provide an overview of the forces that might cause an inflation spike (in a context in which the Philips curve and quantity theories of money are mostly failing) and what asset classes might be the winners in such a scenario

The post-pandemic reflation and causes of inflation

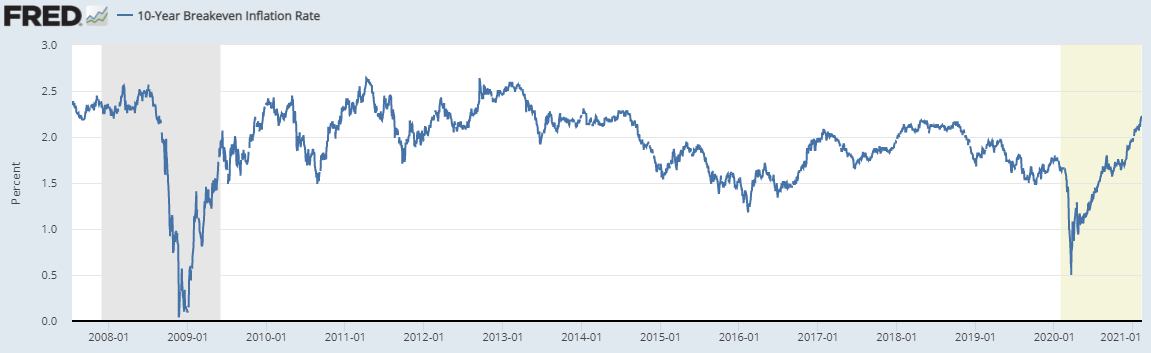

The Covid pandemic generated multiple unprecedented macroeconomic conditions. Predictably, while not dipping in deflationary territory, US inflation indexes in 2020 greatly slowed their growth. One of the main drivers of this decrease was the lack of consumer expenditure as a result of global lockdowns. This same lack of consumer expenditure significantly increased the personal savings of US citizens

Source: FRED

Following an ease in US lockdown restrictions, in August the monthly inflation rate hit a 30-year height as savings sharply dropped. (past sharp drops are mostly explained by tax issues ex. Jan 2013) due to massive increases in expenditure. It is reasonable to assume hence, that when coronavirus policy restrictions will ease globally (and consumers are confident that the crisis has been solved), there might be a brief, demand driven, inflation spike, even at a global level, as savings are rapidly depleted. This assumes that the savings rate is not permanently settled at this “new normal”

Yet such an effect alone is not enough to explain increased inflation expectations (which as we have seen persist beyond the 2-year level). The elephants in the room are the expansionary policies that are being adopted by governments and central banks globally as a response to the pandemic. In the US the fiscal response has been extremely strong, even compared to other countries: Amongst the G7 the US had the largest %GDP budget deficit in 2020 at -18.8%

Fears of hyperinflation due to expansionary policies are not new: following the GFC the idea that QE might cause massive inflation was quite widespread in the public (if much less so amongst economists, and absent from market indicators). This did not materialize: the money that was “created” went all into bank reserves which increased exponentially, the monetary base expanded, but M2 stock lagged behind, as reserves were not lent out. Hence following 2008 monetary policy assumed a new more controlled form, based on setting floors on rates on reserves. Reserve requirements where eventually abolished in March 2020, not only because of regulatory easing due to the pandemic, but mostly because they had become pointless due to their massive amount.

It seems indeed that in post QE economies the monetary base does not influence CPI or core inflation. Instead, the main contribution that monetary policy is likely to give is expectation management and anchoring. This is noticeable even in market indicators: as we can see from the graph below, the spread between forward breakeven inflation rates became essentially zero since 2014 (2 years after inflation targeting was explicitly adopted by the fed, although implicitly it was accepted since the early 90’s, and immediately after the taper tantrum in 2013). This suggests that inflation anchoring has become much more ingrained in investors, with decreasing inflation risk premia for long run break evens and a flattening curve in general for inflation expectations.

It is hence unsurprising that the markets would expect reflation following “pro-overshoot” statements from the fed, given the great credibility of the institution.

Ultimately the discriminating factor for long term inflation is hence fiscal policy. We have already seen that in the USA, where the fiscal response was quicker and stronger than in Europe, inflation (and growth) rates have picked up quicker. In 2021 the US is expected to have a budget deficit of -10% (without including potential infrastructure packages), the second largest (the first position being 2020) since WW2. The effects of this stimulus are in addition likely to be more broadly shared across society compared to Trump’s tax cuts. This presents unique inflationary risk: as lower classes of income spend marginally more on consumer goods/services, this stimulus will almost certainly have a more than proportional inflationary effect compared to the tax cuts, assuming that there is no uncertainty about the future to incentivize saving. This would be compounded by the “savings consumption effect” which was previously discussed.

As a short-term inflation spike appears inevitable, the question moves to its sustainability in the long run.

A longer-term reflation?

As mentioned before we have two conflicting views: Inflation will be transitory during the recovery or it will persist and force the Fed to tighten monetary policy. Which of these two scenarios will prevail is speculative territory, but we can guess how and why one of these scenarios will assert itself.

Currently the market is clearly expecting scenario 1 to come to fruition: While shorter term breakeven inflation rates have hit decennial record levels, longer term measures have not risen as much, as can be seen from the graph below.

Source: FRED

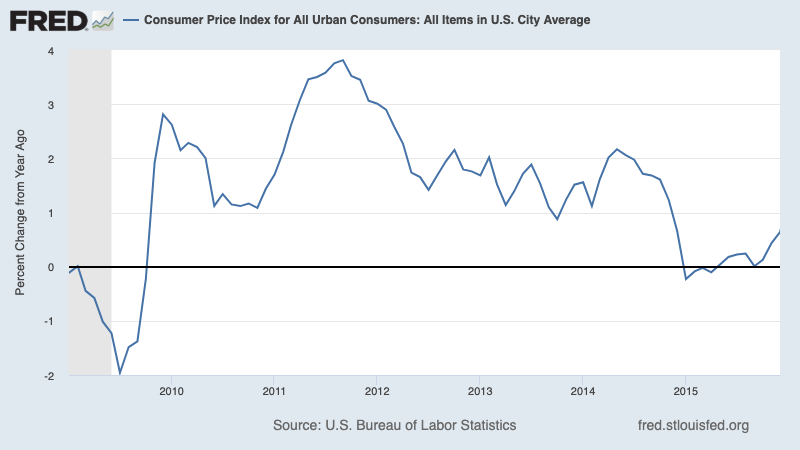

Additionally, as mentioned before, breakeven inflation does not exactly match with realized inflation, as it includes the inflation risk premium. Lacking exogenous factors, which we will analyze later, whether inflation keeps up depends entirely on the credibility of the fed. Allowing inflation to overshoot posits a “legitimacy” issue: used to many years of stable and low inflation a sudden spike, even if short lived, might spook investors and the general public alike, making businesses set prices in expectation of sustained inflation. Yet historical evidence points to the ability, even in these conditions, for the fed to keep control, even without rising rates. The example, pointed out by Paul Krugman, comes straight from 2010/2011

Source: FRED

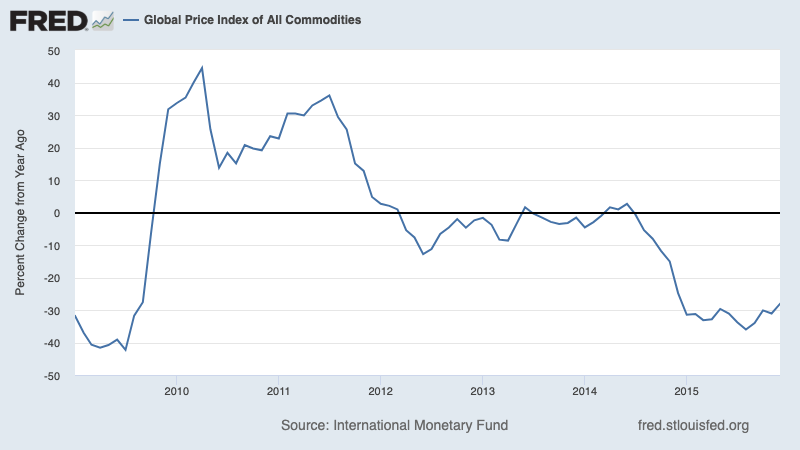

CPI rose by nearly 4% in 2011, yet inflation quickly went down with no rate hike at all from the fed. The same could be said for the trend of prices in commodities, which similarly have experienced a boom in Q1 of 2021, reaching 6-year nominal price records.

Source: FRED

Reasonably we can hence expect that the anchoring of expectations should easily resist a short blip in inflation, although we lack a large enough historical sample size to conclude this with certainty (it is useless to use this kind of data prior to 2009, given all the changes in the structure of monetary policy).

Yet we need to account for additional exogeneous risk factors that might come with the post pandemic recovery and were previously absent in 2010/2011. The Alaska meetings did not show a thaw in Chinese-American relations, in fact the two countries issued reciprocal targeted sanctions to each other only a few days after. An even more intensified trade war, in such a vulnerable moment for CB credibility, could mean a sustained inflation push, as a lack of a large enough domestic investment in manufacturing in the USA or its sphere of influence translates into a supply side shock. While the Trump administration was capable of decreasing trade imbalances towards China since the start of the trade war in 2018, approximately half of the lost deficit was absorbed by countries in south east Asia: a region of interest for China, which seeks to slowly transfer its manufacturing base there. If the United States loses its foothold in the area as a result of heightened trade tensions and an unsuccessful China containment policy, it would result in potential supply chain disruptions. In fact, if tensions persist, this region will certainly be the first true battleground between the two great powers.

Another exogenous source of sustained inflation risk is trickier, and much less likely to manifest itself during the Biden presidency, but is still worth mentioning. Governments across the globe have to enact environmental policies aimed at completely curbing carbon emissions. If these policies were quite successful in the past, it is likely that the cost of the same will increase in the future (by proxy, generating inflation due to supply chain pressure), especially as a required improvement in greenhouse emission performance will have to come from heavy and light industry rather than the energy production industry which has responded with far more ease. Carbon prices in the ETS market in Europe for example, have reached new records, far above previous projections.

If the ecological transition in non-energy industries proves harder than expected, we might witness another source of inflationary pressure, especially if provisions are undertaken to avoid carbon leakage (either in a multilateral or unilateral way). Overall, considering the pro-environment stance of Biden-Harris, the administration might set the stage for these issues in the future.

Both scenarios seem unlikely as of this time, indeed markets do not point to these things being an issue at the moment, nor did they react significantly to the Alaska meetings, perhaps expecting that ultimately China-Us relations will ultimately have little effect on markets, as in 2018-2020.

Winners and losers of reflation

We conclude that scenario 1, a brief spike in inflation followed by normalization, is the most likely scenario in the absence of exogenous effects, while scenario 2 is unlikely, but the chances increase if the risk factors mentioned manifest themselves. Yet, what asset classes might be the winners in both these scenarios?

First, we need to consider the fact that the massive expenditures of the US will result in an exportation of both growth and inflation, especially in favor of emerging markets. Indeed, a stronger EM equity performance appears to already have been priced in by markets, as the MSCI Emerging Markets ETF reached new records not seen since before the financial crisis.

Research published in the Silver Bullet of Algebris points to the contagion effect which an increase in long term rates due to inflation expectations would have on the yield curve of the German Bund (which obviously is the benchmark for Europe as a whole). Not only would it change as a result of increased inflation in the US, but FX hedged spreads between 10Y’s in the US and Germany appear to have reached new heights

Source: Bloomberg, Algebris Investments

Meaning that a likely inevitable tightening of the spread should push up longer term bund returns, as they follow the increased yields of US treasuries.

A steepening yield curve would go in the advantage of European banks, improving their NIM and of life insurance firms, due to balance sheet effects. Worth mentioning is the fact that European bank P/E are still far below historical averages, meaning that they may present a potentially undervalued opportunity.

Obviously, commodities and “hard assets” such as real estate (and potentially cryptocurrencies) are positioned, as history suggest, to be great winners in a reflationary environment. In particular, investors suggest focusing on pro cyclical commodities (such as oil) rather than anti cyclical ones such as gold. Indeed, the performance of gold would be very much dependent in a scenario of persistent higher inflation on the reaction of the fed (rate hike or setting a permanently higher inflation target?). In addition, the two exogenous risks that we mention (which essentially boil down to supply chain disruption), enhance this pro cyclical stance.

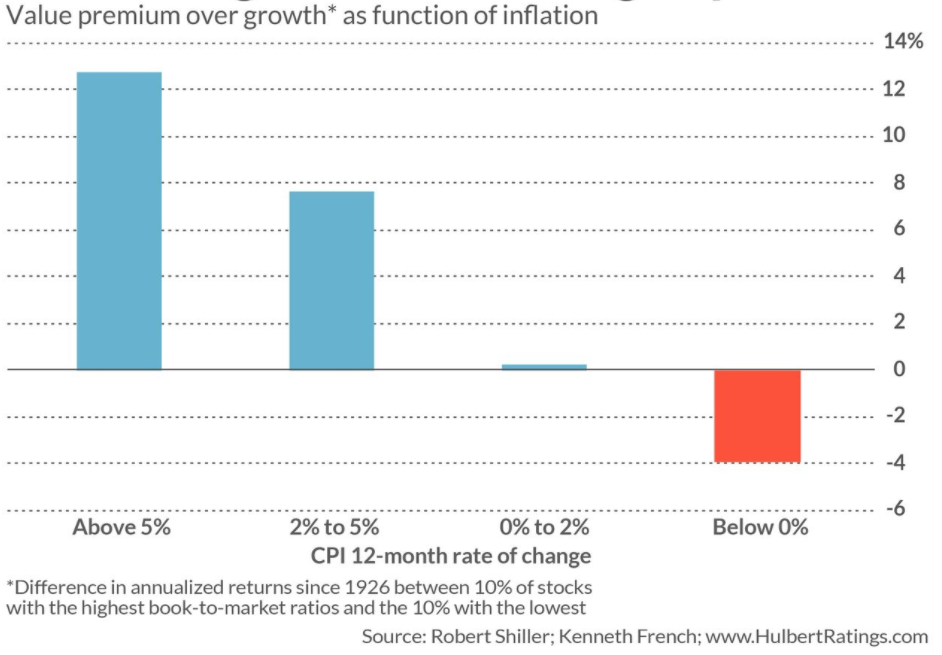

Source: Robert Shiller, K. French

Finally, investors might want to rotate into value equity from growth equity: Historically, inflationary environments have compensated value stocks over growth stocks (above we see average value premiums in HmL). This may be attributable mostly due to increasing interest rates (due to expected inflation) lowering the PV of long-term cash flows in a much more than proportional fashion to shorter term PV’s.

0 Comments