Introduction

Sweden has been widely regarded as a model for social welfare and economic prosperity, and its housing market, GDP, and inflation rates are key indicators of its economic stability. However, the Swedish housing market has been a source of concern in recent times, with some claiming that rally in real estate was unsustainable. In fact, the rally did end early last year when Sweden faced challenges in balancing the sharp decline in its property sector with its economic growth and keeping inflation rates in check. The outlook for 2023 might be even worse. Sweden is the only European economy expected to contract during the year. With the inflation rate still hovering above 10%, the central bank does not have anything else left to do but continue hiking rates. In this article, we will explore the interconnections between Sweden’s housing market, GDP, inflation, and monetary policy, and how they impact the overall economy.

Housing

It has not been an easy year for the Swedish housing market. Since March of last year, the Swedish housing price index has declined by around 13%. To understand why this is happening, we first need to explore the reasons for the boom in property prices before the current decline.

Source: Statistics Sweden

The current housing system started to develop after the Swedish housing bubble popped in the early 1990s. Before that, the aim of the government was to achieve equality in housing through subsidies, rent control, and a large public housing sector. However, in 1992, ownership was encouraged by legalizing conversions from public housing to cooperatives. Subsidies were also largely reduced.

To fuel this transition, there was a need for easier access to credit. That is where the government mortgage bank (SBAB) comes in. It was set up with the aim of encouraging competition and thus lower interest rates for mortgage loans. It has been in the forefront of lowering credit standards. For example, before the 2000s, there was a differentiation made between single family houses and co-ops. Borrowers with co-ops were given less favorable terms for their mortgage loans because they did not actually have tangible property, but just a membership to the co-op. This included higher interest rates and lower Loan-To-Value ratios. Another reason for this is that the co-op itself is often levered, which is an off-balance sheet liability for the member of the association. SBAB was the first bank to ignore the differentiation between co-ops and single-family houses, and the other banks soon followed. SBAB was also responsible for allowing higher LTVs from 70% in 2003 to 95% in 2005, while at the same time lowering the interest rates.

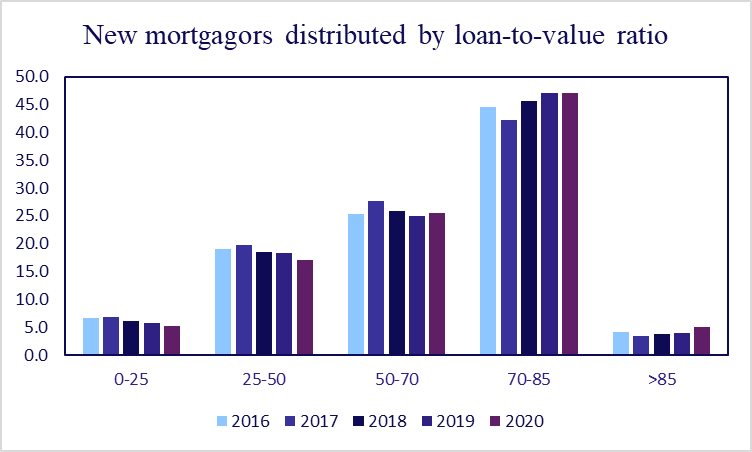

In 2010 an LTV cap of 85% was set in place, but you could still borrow the remaining 15% uncollateralized. In 2020, 3.6% of borrowers supplemented their mmortgage loan with an unsecured one.

Source: Finansinspektionen

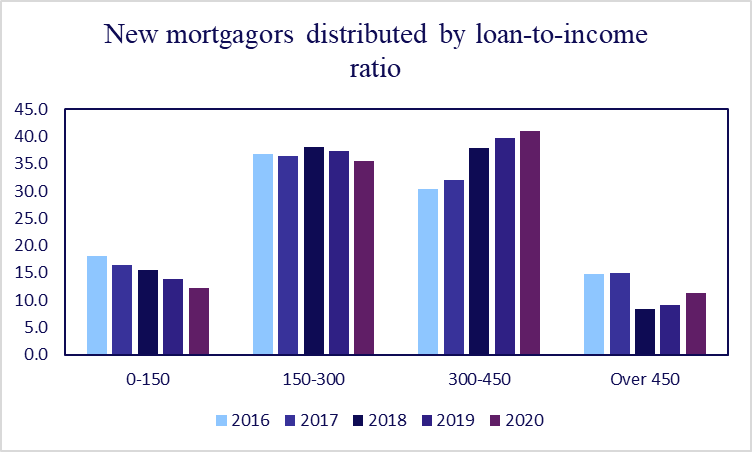

Household budgets were becoming increasingly stretched with more than 50% of households having a debt-to-income ratio north of 300%. The banks did not seem to care. To combat the excessive household debt, the Finansinspektionen introduced stricter amortisation rules to deleverage households faster.

Source: Finansinspektionen

There is another reason Swedish banks are willing to lend so aggressively, and that is the comparatively minimal risk of default. Unlike most countries, in Sweden mortgages are not only secured by the collateral, but also guaranteed by the borrower personally. Since in Sweden it is easy to track a borrower by their personal ID, banks can theoretically pursue them forever. Additionally, the Swedish Enforcement Authority is one of the most efficient institutions in Europe when it comes to collecting debts through liquidation. The average liquidation period is 1 year, and the cost is 9%. The agency can even collect money from the company paying the debtor’s salary.

Taking all these factors together allow banks to lend aggressively with low interest rates, and without considering high risks of default. As a result, housing prices rise.

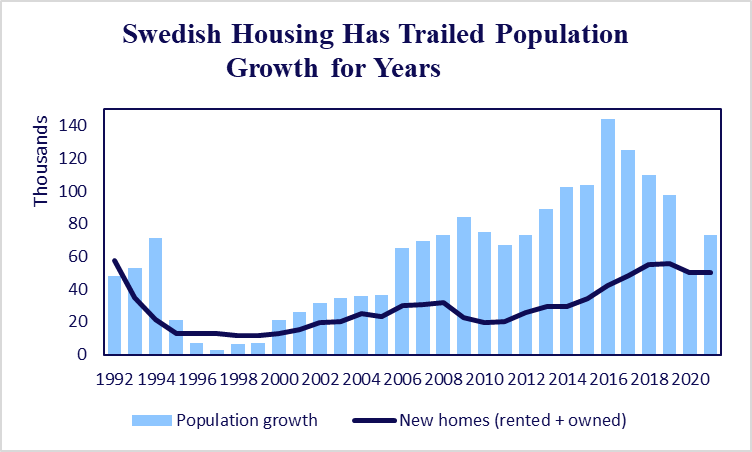

It seems to be a widespread opinion that house prices will be supported by a supposed housing shortage. As evidence for this, usually people share this graph, showing that new-construction in Sweden has been trailing population growth for a very long time now.

Source: Statistics Sweden

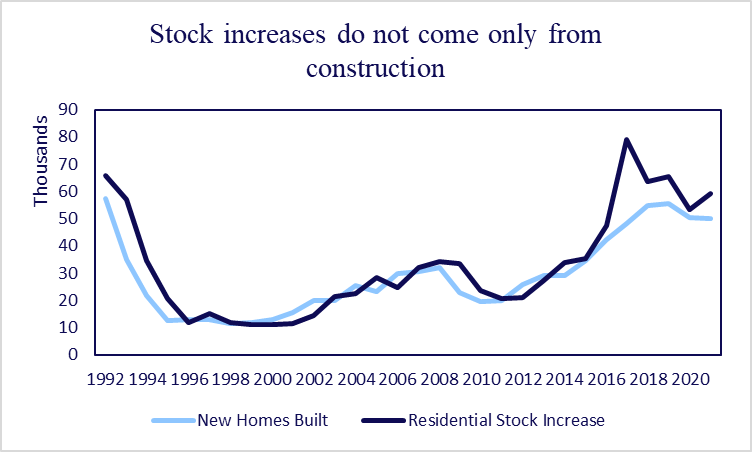

That is true, however it is important to understand that new construction is not the same thing as housing stock, and that is a very important distinction when we are looking at the Swedish housing market.

Source: Statistics Sweden

As we can see from the chart, the increase in residential stock outpaces new builds by a lot. That is because many unusable industrial buildings are converted into residential homes. These conversions do not count as new builds, but increase the residential stock significantly.

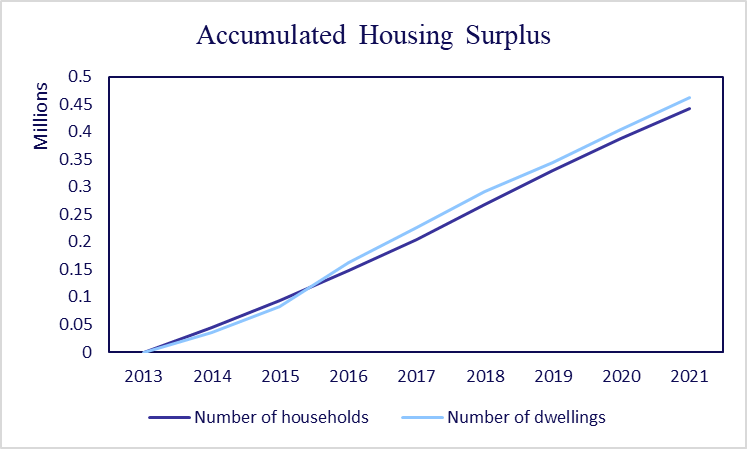

Source: Statistics Sweden

As we can observe from the chart above, from 2013, the number of dwellings has increased faster than the number of households, meaning that there is an accumulated housing surplus, rather than a shortage. The Swedish housing market is said to have been in balance in 1975 when the “Million Homes Programme” was completed, and since then, the accumulated housing stock has increased much more than what can be seen on the graph. Stockholm is the only exception to this rule, since there people outnumber available beds. One reason for the shortage in Stockholm is rent control. People have to wait on average around 9 years to get an accommodation contract, which lasts for life, and as more people move to Stockholm, it becomes more difficult to acquire one.

Even though credit standards are not very high, the recent slump in the property sector is not really caused by a banking failure, or people defaulting on their loans. Rather, it is caused by the type of financing chosen by borrowers.

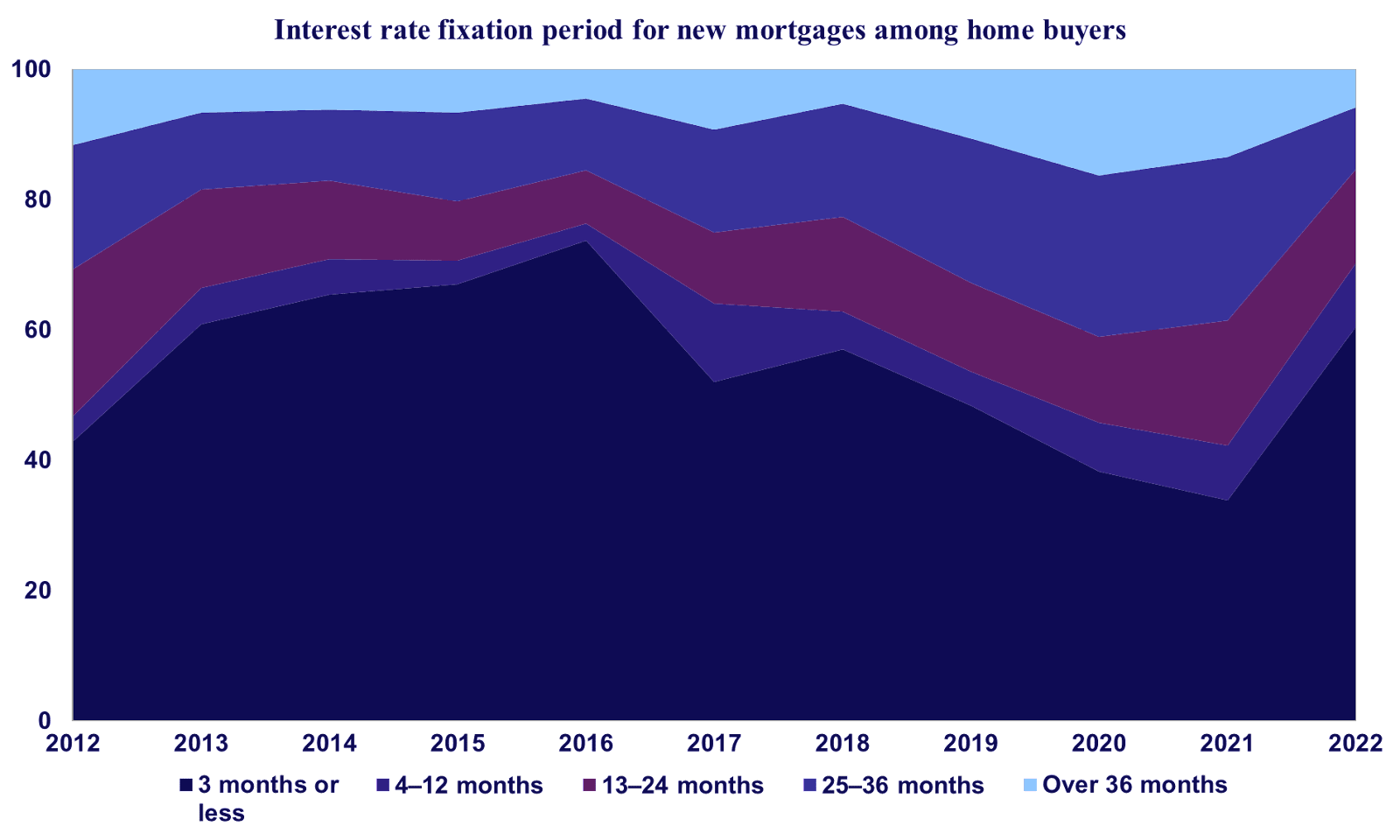

Source: Finansinspektionen

Close to 70% of Swedish mortgages are financed through loans with fixation periods of less than 1 year. The reasons for choosing this option are quite simple. First, fixed rates demand an “insurance” premium by the bank that will cover potential losses in case of interest rate hikes for example. This means that fixed rate loans generally have a higher interest rate in times of low rates volatility. Second, Sweden offers one of the lowest variable-rate mortgages in Europe, and thus it seems more attractive for its citizens to choose it. As we can see from the chart above, the share of loans with a fixed interest rate for 1 year or less increased significantly during 2022. The Riksbank explains this with the fact that the yield curve was still upward sloping at the front end at this time. The third reason is that in the low rates volatility environment of the past decade, people were not expecting rate hikes. Consequently, when the Riksbank started raising rates to contain inflation, the housing sector started a yearlong decline.

That is a big problem for both households and banks. As we saw earlier, Swedish households have remarkably high debt to income ratios, so even slight changes in the interest rate they pay can lead to large effects in their budgets. This can seriously eat into savings and put more stress on already struggling families. Depending on how households adapt to the decrease in saving, this can have varying effects on consumption, but they will be negative.

Banks mostly use covered bonds to finance their mortgage books. Covered bonds are a type of security that is guaranteed by the bank, where the investor also gets a first lien on a pool of mortgages. This makes covered bonds safer than unsecured investments in banks and thus have a lower interest rate. They are like an asset-backed security, but the bank is liable for any losses. Swedish law requires covered bonds to meet certain criteria. First, the mortgages making up the pool must exceed 102% of the value of the bond, and second, the LTV of those mortgages must be under 75%. This is a cheap way to finance mortgages as long as housing prices stay constant or rise. The problem is that when prices fall, the LTV rises, and to keep it under 75%, the bank needs to cut loan notional from the covered bond pool and fund it in another way. Looking at Swedbank as an example, the average LTV in the cover pool is 50%, and their overcapitalization is at 208.9%. As we can see this is far from the limits. The bank started to increase its overcapitalization level in March last year when it was only 129.9% and has been trying to defend the 50% LTV as well by moving SEK100,000m from the covered bond pool. This means that a larger amount of the mortgage book is funded in another, more expensive way. Some of that is transferred onto the borrowers through the floating rate, but the bank absorbs the rest and eats into its margins. Both of those things do not aid recovery in the housing market.

House prices stabilized in the first 2 months of the year, reflecting lower expectations for mortgage rates, and improved housing price expectations. We believe that this stabilization is only temporary and is unlikely to stop prices from falling even further. Even though construction has slowed down, there is still an oversupply of housing, which does not support a stabilization of prices. Also, the interest rate is likely to increase even further because of more central bank rate hikes and higher funding costs for banks, as a result of them being forced to reduce their loan notional from the covered bond pool. These factors lead us to believe that a larger than 20% decrease in housing prices is to be expected from their peak last year. This will have a negative effect on consumption and consequently slow down GDP growth.

Outlook on GDP and Inflation

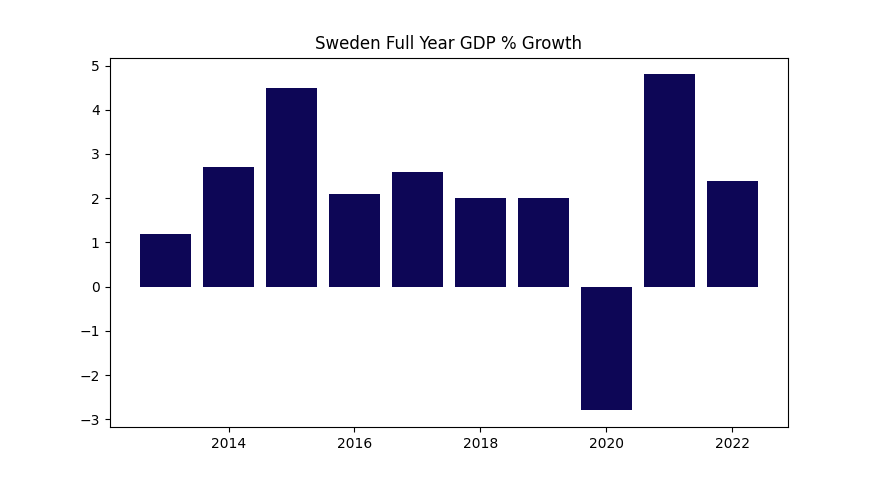

The Swedish economy has grown by 2.4% in 2022, supported by a powerful carry over from the strong 4.8% expansion recorded in 2021.

Source: Statistics Sweden

In the context of a large trade shock with import growth driven by an increase in investments, net trade has outpaced export growth, and total fixed capital formation has been well maintained thanks to strong company balance sheets. However, over the end of 2022, private consumption has been constrained by high inflation, as we are beginning to see a loss of disposable incomes, and rising mortgage debts, amidst monetary policy tightening. Because of this Sweden’s GDP contracted by 0.9% in Q4, exceeding the flash figure of a 0.6% fall, and reversing the 0.2% increase recorded in Q3.

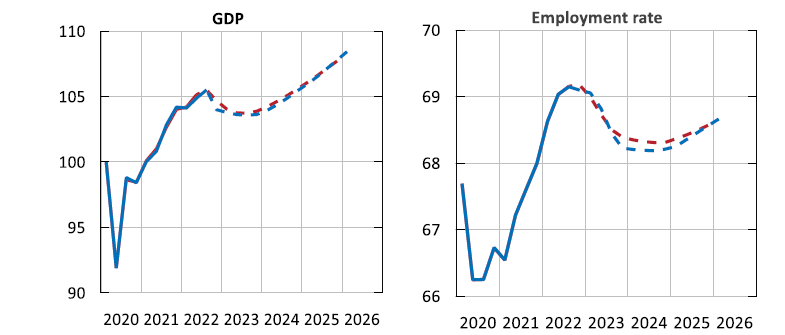

Source: Statistics Sweden

The economy is expected to continue contracting in the first half of 2023, before accelerating later that year, as Sweden’s central bank is committed to keep raising policy rates, until inflation is brought to its original target of 2%. In the Swedish economy, sensitivity to interest rates is higher than before as a result of households’ increased indebtedness and the short interest-rate fixation periods on their mortgages. Even from an international perspective, it appears that sensitivity to interest rates is higher in Sweden than in many other economies, which further increases the impact of interest rate adjustments to disposable income. Because of that households would need to further decrease consumption spending in response to the loss of disposable income, and rising unemployment. From the third quarter of 2023, consumption growth is expected to moderate as inflation shocks subside, real disposable income recovers and the housing market slows. Construction activity is expected to decline sharply in 2023 due to lower demand, and higher costs.

Source: Riksbank

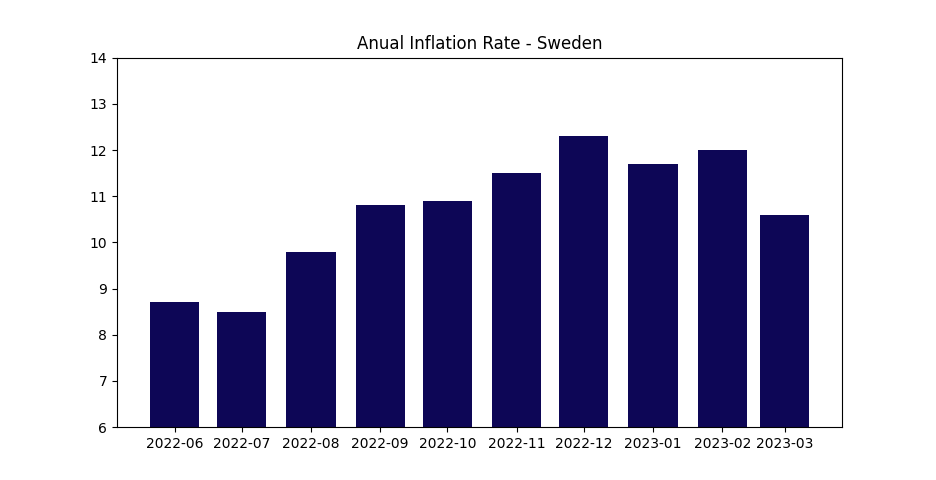

Taking a closer look at inflation, Sweden’s CPI eased to 10.6% in March 2023 from the 12% rise in the previous month, beating market expectations of a 11.1% increase, making it the lowest reading since August last year.

Source: Statistics Sweden

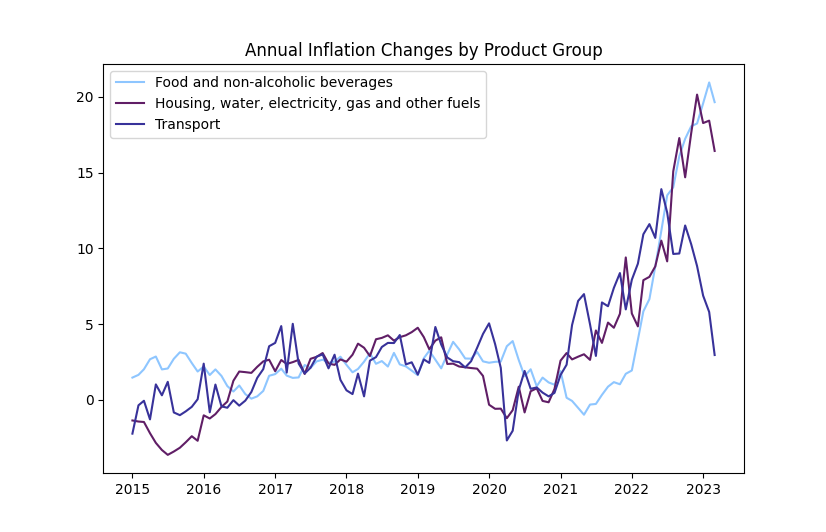

Prices slowed for almost all sub-indexes, mainly due to falling electricity prices which declined by 2.2% MoM, driving down costs of housing & utilities (16.4% vs 18.4% in February), and transport (3% vs 5.8%). CPIF excluding energy marked its first decline since the end of 2021, with slowing costs for food & non-alcoholic beverages (19.7% vs 21%), and a decline in apartment rents. It should be noted that food and housing are the two most important categories when it comes to the calculation of Sweden’s CPI since together, they represent 38% of the total weight of the index (14% and 24% respectively).

Source: Statistics Sweden

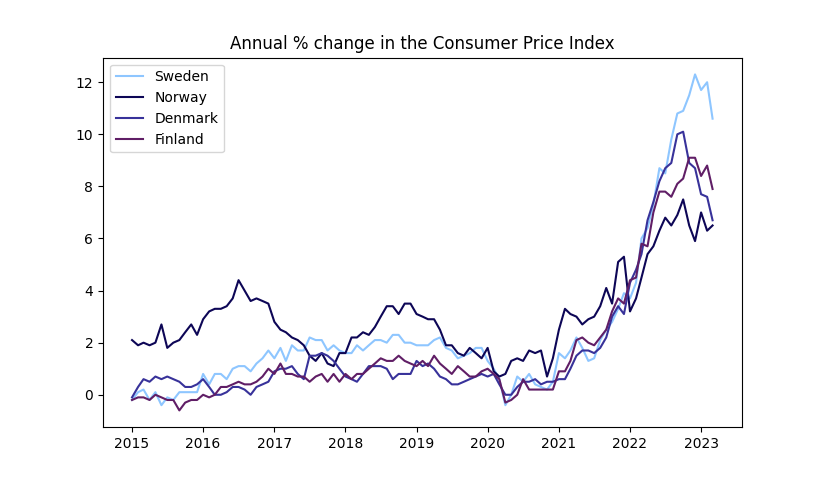

Inflation was also lower in furnishings & household goods (12.9% vs 13.2%), recreation & culture (7% vs 8.3%), and miscellaneous goods & services (6.9% vs 7.4%). On a monthly basis, consumer prices rose 0.6%, down from a 1.1% jump in February and below market estimates of a 1% gain. Compared to the other Nordic countries in the EU, Sweden’s inflation is currently the highest and is the only one without clear indication that a peak has been reached.

Source: Statistics Sweden, Statistics Finland, Statistics Denmark, Statistics Norway

These high rates of inflation can be partly explained by the rapid increase of energy prices. However, CPIF ex energy has also remained elevated as a result of pandemic-related supply shortages, and failure to satisfy the rising demand. In addition, due to the high energy prices a lot of companies needed to raise their sales prices, further pushing inflation throughout the EU. What was different about Sweden however, was the remarkably resilient demand caused by an excessive expansionary economic policy, and a strong labor market. Despite the fact that large parts of the Swedish economy bounced back substantially at the end of 2020, fiscal and monetary policy added almost SEK 600bn, or more than 10% of its GDP, in 2021 alone. QE of numerous central banks led to surges in the stock market causing Swedish households’ financial wealth to increase by SEK 3,100bill during the course of 2021. At the same time, house prices rose by 11% and household debts grew by SEK 300bill. It is not only certain product groups which might have struggled with supply problems, rather, high inflation is observed among all goods and services. On top of that the employment rate in Sweden is at the record-high level of 69.3%, but unemployment is not so low from a historical perspective currently sitting at 7.4%.

Source: Statistics Sweden

This is because the labor force in Sweden has strengthened during and after the pandemic, more than it did in the EU and the USA. Also, unlike other countries where wages are set directly in negotiations between employers and employees, and thus wage-setting is more flexible, in Sweden, due to institutional factors, wage formation is largely centralized and sometimes even indexed, which makes subduing the still strong demand even harder.

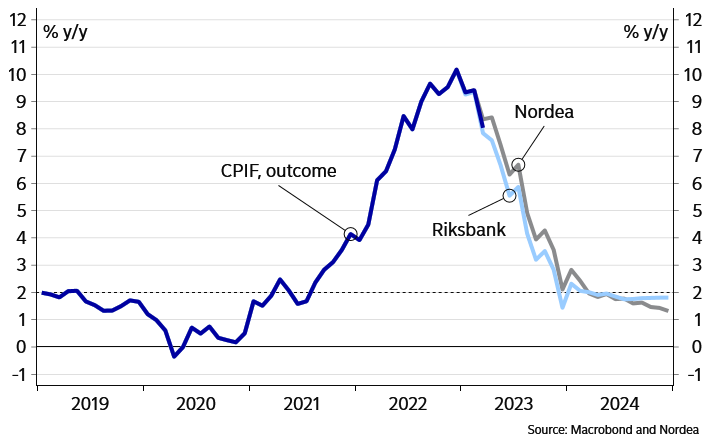

Over the past year, the policy rate has been raised rapidly, and although it may not appear high historically or compared to other countries, the effects on the economy and inflation will occur with a certain time lag, becoming more apparent later this year. Households and companies would continue to face escalating costs, leading to a projected decline in demand and inflation, which is predicted to stabilize back to the 2% by the beginning of 2024.

Source: Bocconi Students Investment Club, Nordea

Economic activity is expected to slow this year, as weaker international demand will reduce Swedish exports, while rising prices and higher interest rates will undermine households’ purchasing power, eventually leading to weaker consumption. The crashing housing market will cause a stall in housing investment, which will further reinforce the economic downturn, as companies’ declining investment are also going to contribute. All in all, economic activity will slow down even further in 2023, weakening the labour market.

Monetary Policy

Alongside other central banks, the Swedish Riksbank (RB) started aggressively hiking interest rates last year to fight the inflation shocks due to the economic recovery from the Covid pandemic, as well as rising energy and food prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. So far, the central bank raised its repo rate from 0% to 3%, including an unprecedented 100bp hike in September 2022. Most recently, the Riksbank raised the policy rate by 50bps after their preferred inflation measure (CPIF) printed at 9.5% and 10.2% for November and December that exceeded the bank’s forecast by 0.8% and 1%, respectively. Further, it announced that starting from April it would start selling government bonds with notionals of SEK3.5bn per month and offer one-week certificates to absorb excess liquidity from the financial system. Finally, depending on incoming data, it indicated that further interest rate increases of 25 or 50 basis points would be necessary at the upcoming meeting on 26 April.

A substantial pivot in the central bank communication within the meeting minutes concerned the commentary on the weakness of the Swedish Krona (SEK). While the importance of the exchange rate channel was seen as having a minimal impact on inflation, several members of the Executive Board expressed a preference for a stronger SEK, citing concerns over changed pricing behavior if the weakness persisted. In this regard, the increased supply of government bonds and the absorption of excess liquidity as potential drivers of a stronger domestic currency.

The implications of the announced quantitative tightening (QT) seem to be significant for the Swedish bond market. Due the comparatively low level of indebtedness of the government (2022: 33% Debt/GDP), the Swedish market for government bonds is substantially smaller than other European countries. This scarcity is also cited as one potential reason for the structural weakness of SEK. Danske Bank estimates that the RB’s QT operation will lead to a net increase of SEK44.5bn in free float compared to 2022 (-23.5bn purchases, 21bn sales). Together with the expected issuance of the Swedish National Debt Office (SNDO) this is expected to increase the free float almost threefold from SEK22.5bn in 2022 to SEK61bn in 2023 and SEK80bn in 2024.

Despite the high realized inflation rates over the last months, data indicates that inflation expectations in Sweden are still anchored close to the central bank’s 2% target. While survey data indicates constant expectations close to but slightly above the target, market-implied expectations dropped off significantly during the year as a stronger economic downturn was being priced in. This factor should support the Riksbank’s job to bring inflation back to target, even though several board members pointed out that this has to be achieved within a short time period to avoid a de-anchoring in the future.

Looking ahead at the next meeting on 26 April, the market is currently pricing in 44bps and further 18bps for the meeting in June. After February’s meeting, the inflation rate continued to exceed the Riksbank’s forecasts with the CPIF ex energy numbers for February and March coming in at 9.3% and 8.9%, respectively. These numbers were 1.3pp and 1.4pp higher than February’s forecast. Further, the SEK continued its weakness with the krona index (KIX) still trading close to its highest level since the financial crisis. Although an apparent peak in headline might have been reached, the pressure on the Riksbank to continue hiking interest rates are likely to persist.

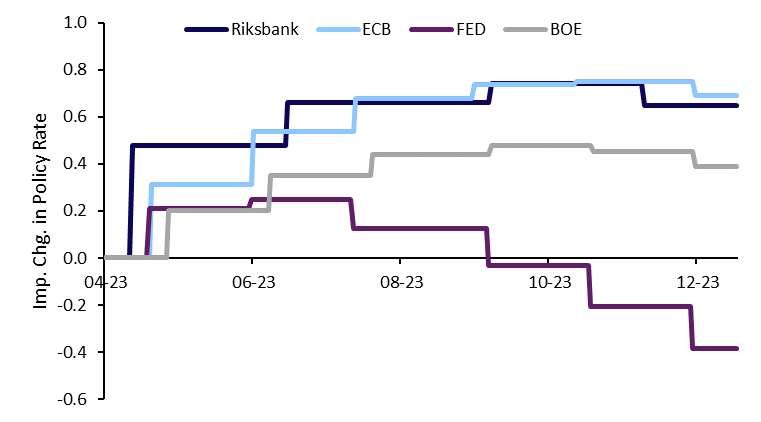

Comparing the current market pricing between with other major central banks, it is evident that the Riksbank is expected to be among the most hawkish over the remaining year. This seems to be consistent with the continued inflationary pressures, as well as the continued weakness of the krona. Further, as the stress in the financial system eased over the course of the last weeks, the fragility of the banking system is unlikely to substantially impact the decision making by the executive board. Finally, the economy showed resilience at the beginning of the year with a strong labor market despite the negative shock to disposable income. Nevertheless, SEK FRAs already imply rate cuts starting from the last of this year’s meeting.

Source: Bloomberg, Bocconi Students Investment Club

Although, it is expected that the Swedish economy will slide into a recession later this year this exemplifies a clear misalignment between the Riksbank communication and the market. Members of the executive board have repeatedly emphasized the importance of bringing inflation back to its target within the shortest feasible time period to avoid a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. In the February meeting, First Deputy Governor Anna Breman stated that “monetary policy needs to be significantly contractionary for a considerable period” and that “[a] policy rate path indicating that interest rates will soon be cut [was] associated with major risks”. Given that inflation numbers since then overshot the Riksbank’s forecast it seems unlikely that this assessment fundamentally changed in the meantime.

Trade Idea: SGB-Bund Spread

Over the course of 2022, the spread between the 10y SGB and 10y German government bond tightened substantially and is still currently trading at negative levels. This constitutes a historically low level with negative spreads not seen in almost ten years.

In our view, there are several factors which should lead to a widening of the SGB-Bund spread. First, inflation continued to exceed the Riksbank’s forecast. In connection with the commitment by members of the Executive Board to bring inflation back to target within a reasonably short time to avoid the de-anchoring of inflation expectations, this should set the stage for a substantial further tightening of financial conditions. In our view, the current market pricing implying rate cuts in the second half of the year appears to be overly optimistic given the broad-based inflation pressures in Sweden. Besides, a “higher for longer” view on the policy rate this could also include a broadening of the QT operations, as long as the Swedish bond market is still robust.

Second, the functionality of the Swedish government bond market is hampered by the low indebtedness of the country’s government. The extensive QE operations during the Covid pandemic led to the Riksbank holding almost 50% of some long-term issues that are eligible for the sale within QT. The described net impact on supply as QT goes live and the disappearance of QE together with the continued new issuance should push up yields substantially.

Although the banking turmoil eased over the last few weeks, we want to avoid taking a view on the further development at this point. The long Bund position therefore should neutralizes the exposure to further shocks to the global banking system with the spread being largely unchanged as both Bunds and SGBs rallied during the latest episode of turmoil.

Source: Bocconi Students Investment Club, Bloomberg, Danske Bank

References

[1] Riksbank. “Account of Monetary Policy.” 2022.

[2] Tresor-Economics. “Lessons for today from Sweden’s crisis in the 1990s.” Sept. 2012.

[3] European Commission. “European Economic Forecast Winter 2023.” Feb. 2023.

[4] Nordea. “Economic Outlook.” Mar. 2023.

[5] Nordic Credit Rating. “Sweden’s real-estate sector faces growing challenges.” 13 Dec. 2021.

1 Comment

Kostadin Kotsev · 17 April 2023 at 1:07

A very well composed and researched paper. I bet whoever wrote it is also extremely handsome.