The Lira, inflation and COVID-19: an overview of the Turkish economy

Political context

Turkey’s political scene was recently in the news with the departure of Finance Minister Mr. Albayrak, a powerful politician and the Turkish President’s son-in-law. The departure of Mr. Albayrak was seen as favourably by investors, since it showed that Mr. Erdogan is now more willing to take the required measures to put the country’s economy back on track.

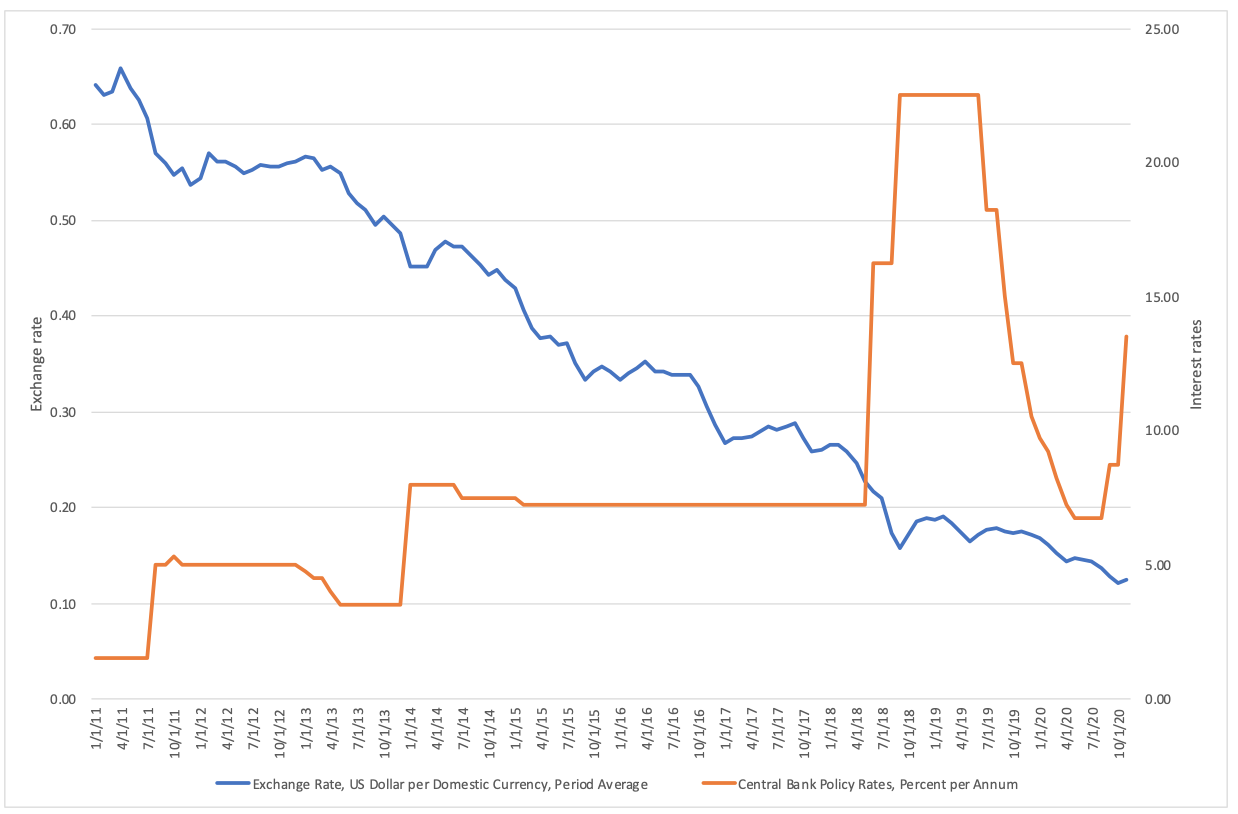

The first interest rate hike was introduced in September but has not been followed by subsequent actions in the same direction, with a much awaited further rise in interest rates being delayed. Now that Turkey has introduced the largest interest rates increase in the last 2 years (the one-week repo rate was raised from 10.25 to 15 per cent), marking the policy direction of a newly appointed head of Central Bank Naci Agbal, investors are finally able to see clear attempts to support the plunging lira. In fact, tightening measures have already been implemented by Central bank through an obscure system of multiple rates, with an average cost of funding for the Turkish financial system of 14.8 per cent, making the new official repo-rate of 15 per cent only slightly higher. Nevertheless, this decision has raised expectation about future stability and predictability of the Turkish economy, and this is a good sign for foreign investors, allowing Turkey to lure back much needed international funds.

The flexibility demonstrated by Erdogan, however, has created instability in his inner circle and supporting coalition, aggravating the difficult situation the President currently faces in trying to resolve tensions between the 2 supporting groups: ruling political party AKP and key political partner MHP, a controversial party gaining power within the system. Mr. Albayrak was seen as Mr. Erdogan’s chosen political heir, however, the appointment of Mr. Agbal as central bank governor, who was known for his criticism of Mr. Albayrak’s policy, was followed by the minister of finance’s resignation. Failure to raise interest rates and the prolonged reliance on consumption and credit has led the Turkish economy to a currency crisis. In attempts to support the lira, around $140bn in foreign reserves have been burnt during the 2 years Mr. Albayrak was in office (further evidence of the Turkish Central Bank’s lack of independence from the government). Lutfi Elvan, a new finance minister whose views are perceived as market friendly, was welcomed by the investors seeking returns in a time of global negative-yielding debt. A number of investors have already increased exposure for a range of asset classes in Turkey. However, as the pandemic turned out to be have hit the country harder than expect (after the revelation of underreporting asymptomatic Covid cases by official statistics sources) and due to Erdogan’s unwillingness to cooperate with the IMF, the recovery of the Turkish economy is still likely to be very slow.

Some degree of support from the foreign investors was already seen, with Qatar, one of Turkey’s most important financial backers agreeing to acquire a 10 per cent stake in Istanbul’s stock exchange, Borsa Istanbul, as well as a 30 per cent stake of Istanbul’s luxury shopping center. This will give a small boost for Turkey, after the country suffered a sharp fall in direct foreign investment reaching $5,6 bn, the lowest level for the last 15 years. The move signals a strengthening in the partnership between Turkey and Qatar. Qatar has previously provided support for Turkey’s foreign currency reserves in 2018, amidst a currency crisis, through a swap agreement for $5 bn. This year, it has expanded its support for the country’s Central Bank to $15 bn. Turkey in return has become an ally for Qatar opposition with its Gulf neighbours UAE and Saudi Arabia.

The macroeconomic scenario

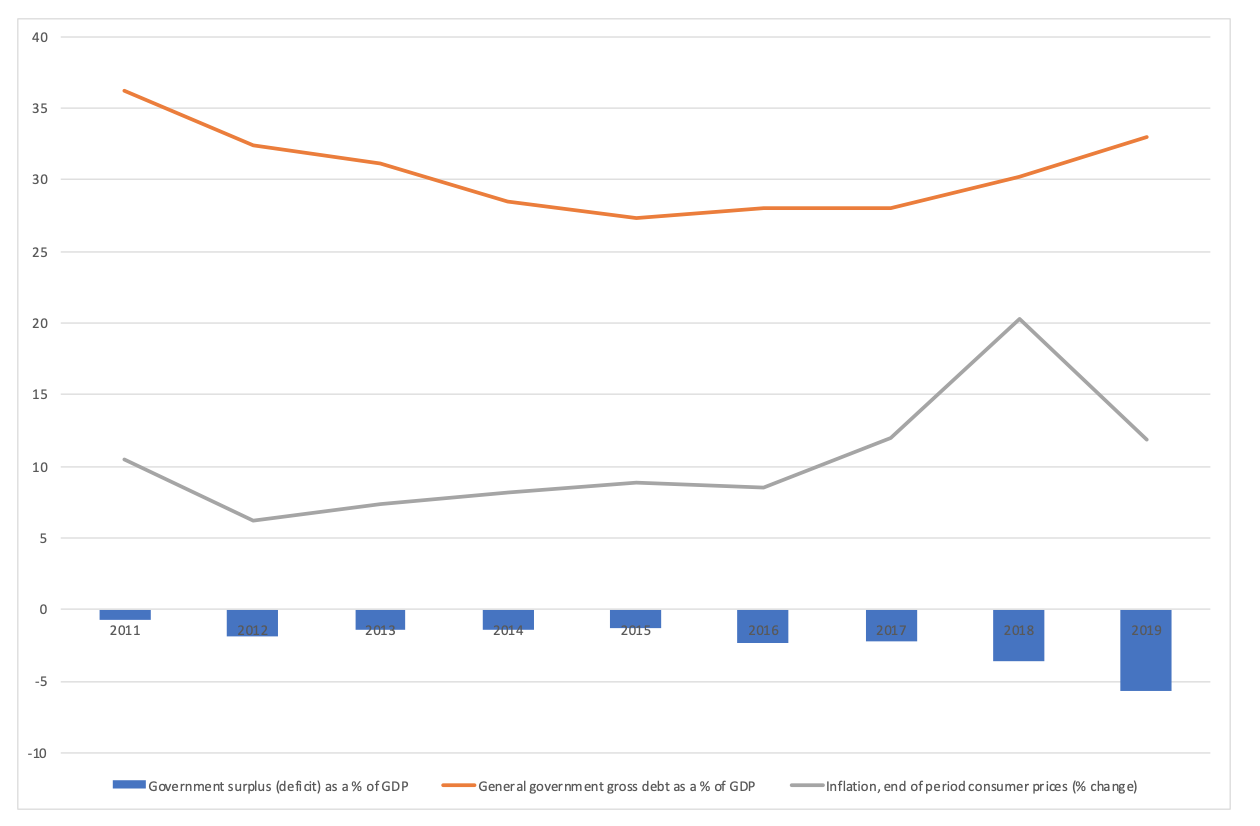

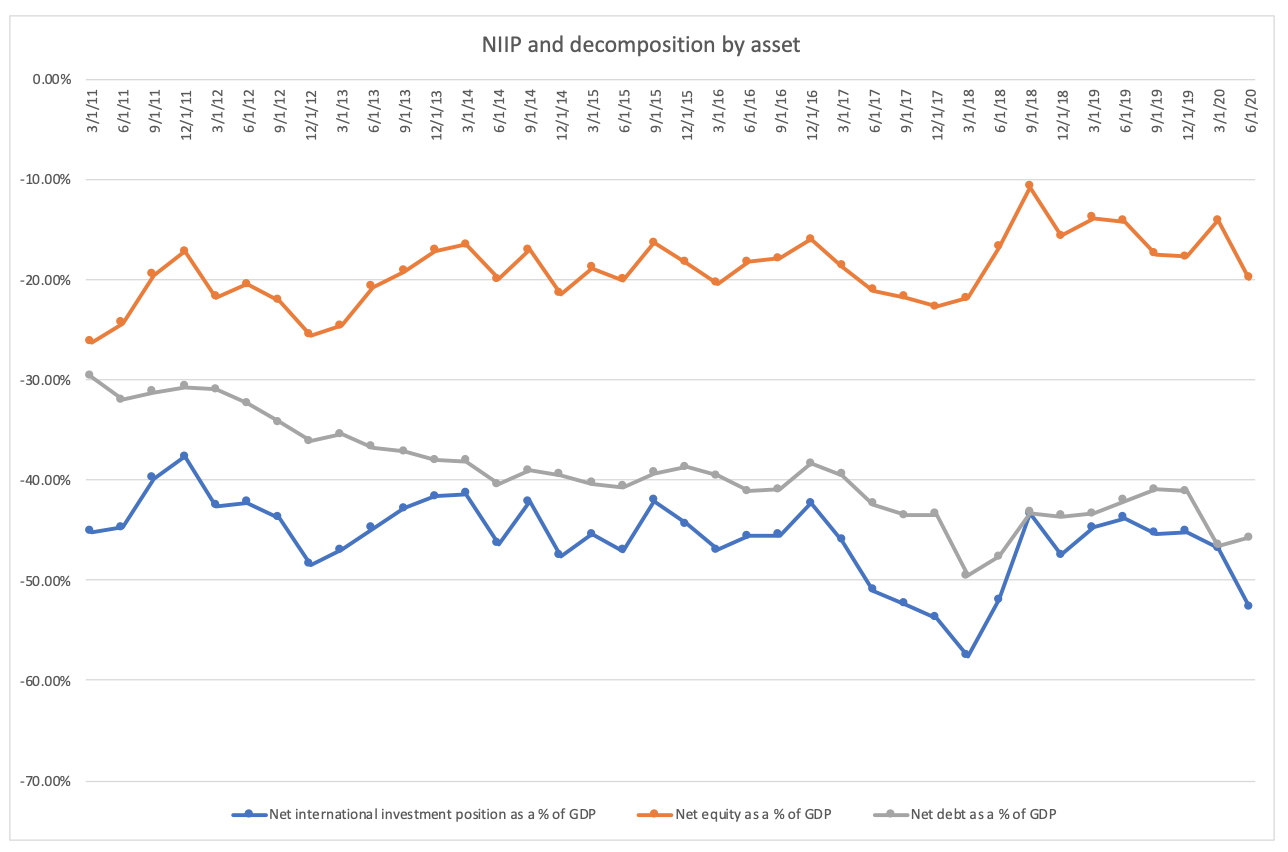

After the Great Recession, Turkey became strongly reliant on externally-founded credit growth and on demand stimulus. The consequences were large current account deficits, mainly financed with debt, a weak net international investment position, large currency mismatches in the private sector, and thus high inflation. The economy was running above potential and was thus vulnerable to changes in market sentiment. This is exactly what happened in 2018: a strong lira depreciation led to high inflation, which policymaker had to tackle with interest rates hikes.

With the help of favorable external financing conditions, Turkey recovered from this crisis using more of the old tools, but this time it was mainly state-owned banks which contributed to credit growth, as private ones had to cut back on their lending due to the losses they had incurred. In 2019 inflation fell and thus interest rates declined, the lira stabilized, the current account turned positive, growth resumed but investments declined, and they were replaced by government spending which led to a higher government deficit.

The COVID crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated economic uncertainty led to a deterioration in sentiment towards emerging markets in 2020. Turkey experienced a lira depreciation of about 20% against the US dollar, big portfolio outflows which lead to a large loss in foreign currency reserves, and its current account turned once again negative. The loss in foreign reserve was incredibly large, they declined by about 50% during the year, far more than what other emerging markets experienced. The key reason why Turkey was so vulnerable to a change in market sentiment is that it experienced a credit boom at the beginning of 2020, which made it very reliant on FX debt.

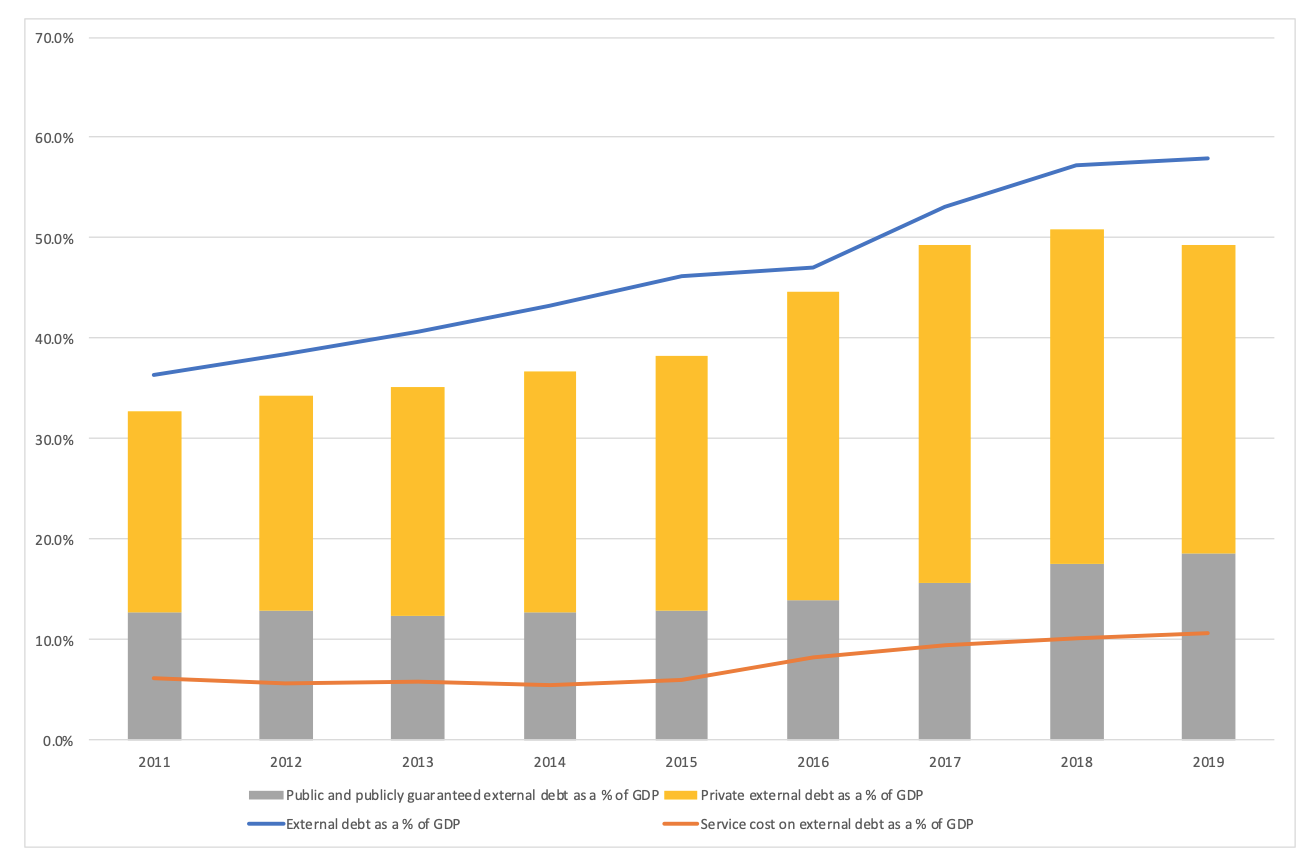

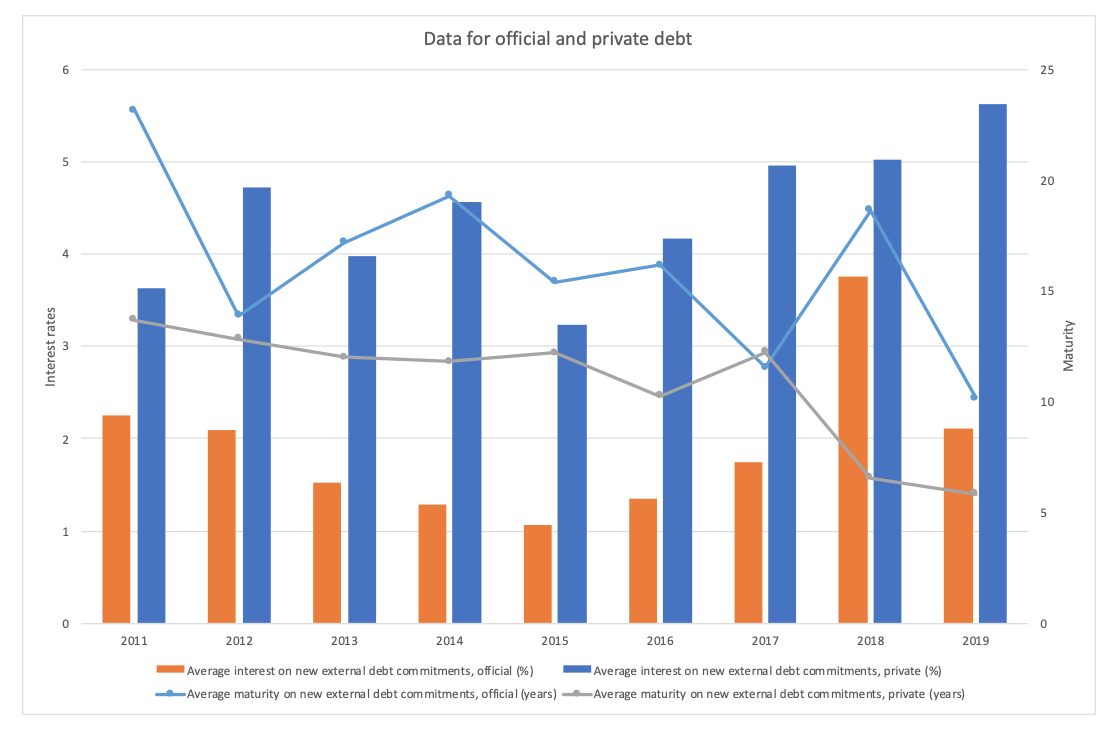

The private sector FX debt was and still is very high. The balance sheet of non-financial corporates had already been weakened a lot by the 2018 lira depreciation because they carried a negative open on balance sheet FX exposure. Thus, they were further hit by the COVID crisis. The government had been increasing its FX debt too, due to the high domestic interest rates and the increasing fiscal deficit. The following graph shows the increase in private and state-backed external debts.

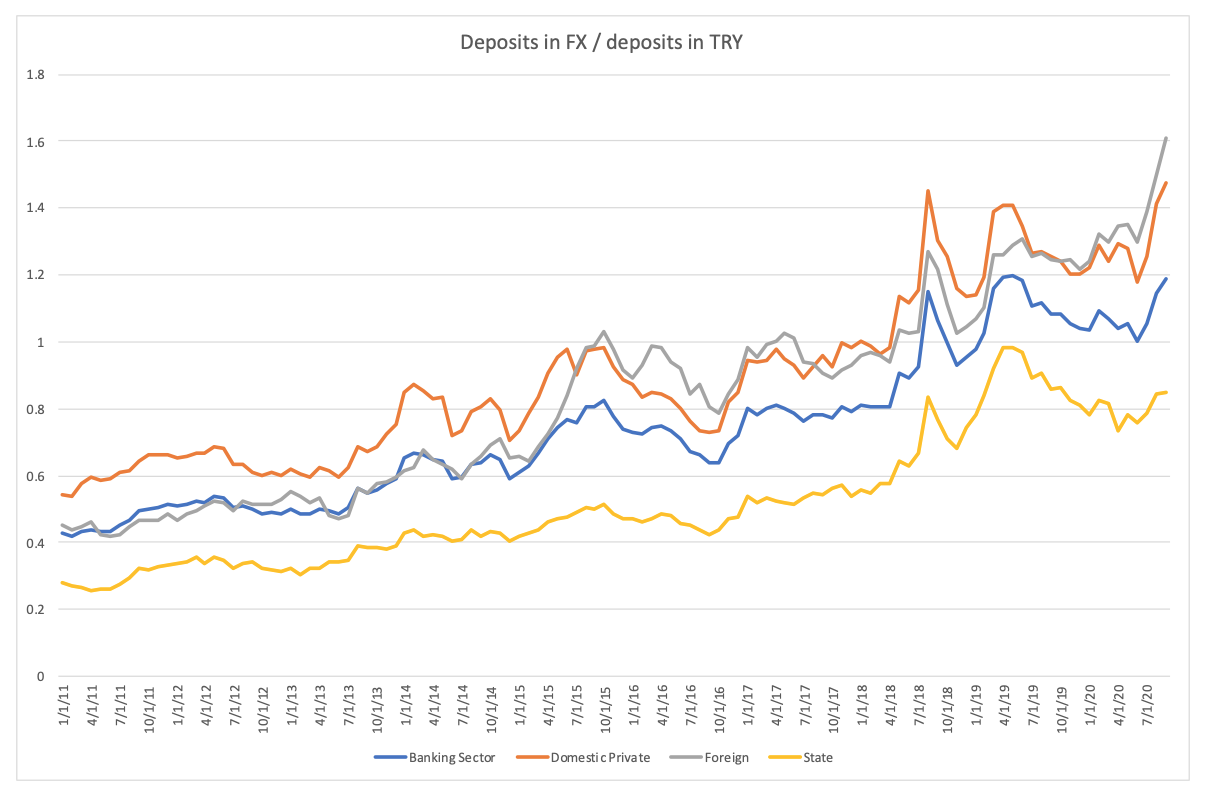

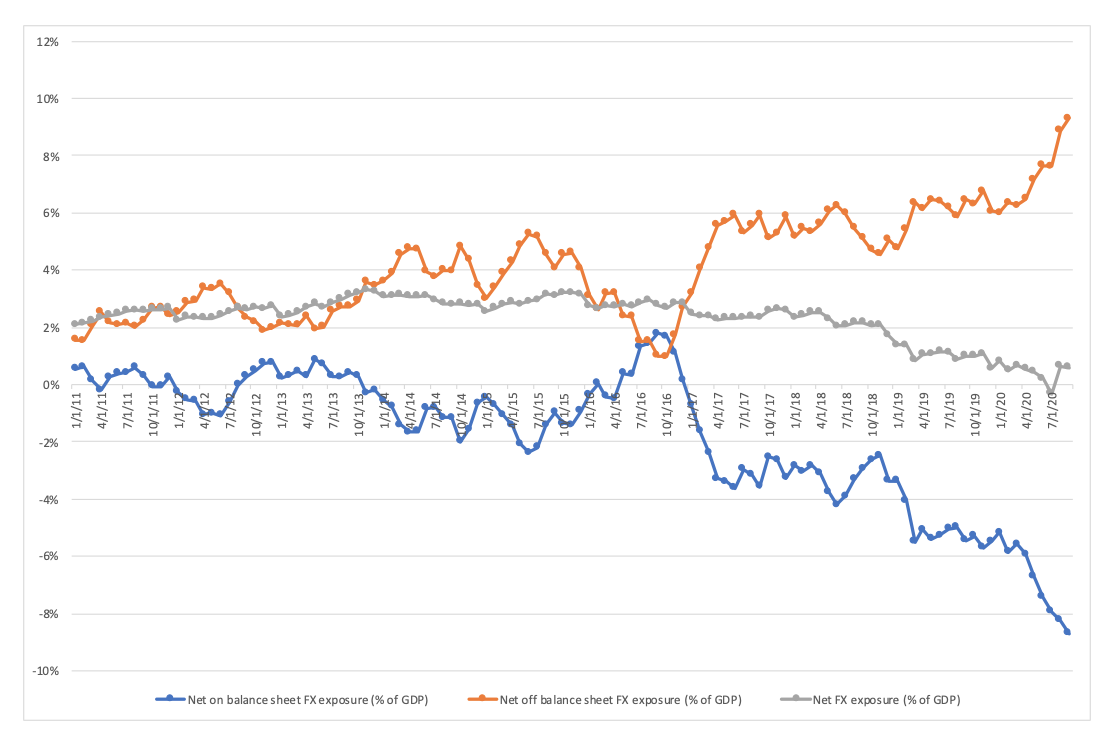

Banks had been stressed a lot by the 2018 lira depreciation, and the consequent high interest rates and low growth. As a result, private banks had cut their lending, however state-owned ones engaged in a massive credit expansion, in doing so they provided credit at rates lower than their cost of funding from the CBRT (Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey). To support their interest margin, they financed themselves mainly in FX, contributing to an increase in deposits dollarization. The following graphs, show that:

- Depository corporation have negative net foreign assets.

- State-backed banks are characterized by a higher loan to deposit ratio.

- Banks are characterized by an increasing deposits dollarization; they are in fact borrowing in FX to lower their funding costs.

- Banks have a large negative on-balance sheet FX exposure which is matched by a positive off-balance sheet FX exposure.

Overall, just before the COVID crisis, external financing needs were high: private banks reduced it, but non-financial corporates, state owned banks and the government increased it. Moreover, the quality of external financing had already worsened: interest rates were rising, and maturities were decreasing.

The policy implications

Turkey has periodically gone through credit-driven booms, which have been the primary driver of the country’s economic growth. However, as we have shown, they left it very exposed to changes in market sentiment in multiple situations. In order to overcome the current Covid crisis, policymakers should undertake structural reforms, and move their focus from credit-driven short-run growth to sustainable long-run growth. Some possible steps are:

- Tight monetary policy: inflation expectations are still high, a tight monetary policy would lower inflation and permanently lower interest rates, boosting the credibility of the CB, strengthening its foreign reserves and supporting the currency.

- Fiscal policy should be neutral to better anchor inflation expectations.

- The credit growth of state-backed banks should be reined in, and their balance sheets should be cleaned up. In this context, a third-party asset quality review and new stress tests may allow to better understand the health of the banking system. In particular, banks have a lot of flexibility in when recognizing impairments, this implies that a deterioration in their asset quality is reflected after some time.

With respect to these points, the recently appointed governor of the central bank of Turkey, Naci Agbal, has immediately strengthened the credibility of the central bank and showed its determination to tackle the increasing inflation rate, increasing the interest rates by 4.75% up to 15%. Moreover, he greatly improved the transparency of monetary policy, removing a system of multiple policy interest rates, marking a shift back to traditional policymaking.

The markets seem to believe that this is a drastic change in economic management for Turkey, the Turkish lira has in fact appreciated following the news of the announcement.

Macroeconomic projections

There is a great deal of uncertainty around how the Turkish economy will evolve in 2021 and the near future. However, we believe that few developments are quite likely to happen. We will now discuss the way we believe the economic rebound expected to take place in 2021 will affect Turkey and how the country’s institutions will take action to stabilize the Turkish economy.

Of foremost importance is the future of monetary policy. As we argued, tighter monetary policy is paramount to rein in inflation and foster price stability. It was announced by the Government in September that their target inflation rates for 2020, 2021 and 2022 are, respectively, 10.5%, 8% and 6%. We do not believe that these are achievable, especially since the country’s Central Bank expects inflation to hit 12.1% this year and 9.4% the next.

Investors are hesitant to pour money into lira-denominated bonds as they want to see a clear signal from Turkish institutions that curbing inflation is their top priority. It seems likely that the Central Bank will take part in market auctions to increase its stocks of dollar reserves, mainly because the amount of dollar reserves currently owned by the Central Bank is lower than the amount it owes to commercial banks in Turkey. That could have the effect of further devaluating the lira against the dollar, making a rate hike even more strongly needed to offset such a negative development.

Furthermore, it is interesting to observe that Mr. Erdogan has suddenly become a proponent of tighter monetary policy, possibly recognizing the cogent and pressing necessity to take action against inflation and to attract investor, thus stopping the capital outflows that have been observed in recent months. We believe that this will make further rate jumps even more likely and that investors’ expectations will factor them in, considering the widely accepted view that Mr. Erdogan’s influence on the Turkish Central Bank is all but weak.

Another important factor to look out for is the amount of fiscal stimulus that the government will continue to provide in the upcoming months. Several factors, in particular the spike in the number of impoverished citizens, make enhanced stimulus measures appear more likely well into 2021. If this has the impact of increasing domestic consumption, however, the drawbacks might include a further worsening of the credit account deficit and stronger inflationary pressures.

Finally, a significant role will be played by international investors. We project a notable capital inflow from investors in Europe and the US seeking higher yields than those they could get investing in European and American fixed income securities (which are projected to keep yielding low returns in the upcoming year, due to loose monetary policy). We therefore expect investors to move to emerging markets credit, and Turkey is well positioned to benefit from this possible development.

We will now move on to the outlook we envision for the main asset classes.

Equity markets

On the basis of our macro-projections, we expect that equity markets will deliver positive real returns over the coming decade. If monetary and fiscal authorities enact sound policies, they could manage to bring down inflation, interest rates will thus permanently decrease, and the economy will grow sustainably over the long run. Turkey would thus go through a disinflationary decade, characterized by positive real growth. Such as environment, would be similar to the 1980’s decade of the US, and just like in that case, equities could perform very well in both nominal and real terms.

Bond markets

Tight monetary policy of the Central Bank with the continuation of the current trend of hiking rates in the nearest time will increase the average funding cost for the financial system of Turkey, pushing bonds’ yields higher.

However, in the long-term, despite the fact of unlikely possibility of the Turkish government to meet the target level of inflation of 10.5% this year, as well as the following targets of 8% and 6% for the years 2021-2022, actions aimed to curb inflation in the following years will have a positive impact on the bonds’ prices, while lowering bonds’ yields. This would happen because a lower inflation will increase the purchasing power of the earnings investors gain as bonds matures.

The credit rating of Turkey, which has followed a trend of reduction since 2014 is likely to slow down and remain steady in the medium-run perspective following the change in the country’s attitude to currency support and keeping in mind the fact the Turkey is one of the strongest economies in the emerging markets field with higher chances of fast recovery after the Covid crisis. Stable credit rating would be an additional stimulus pushing the price of bonds higher.

Commodities

Monetary conditions are often considered as a key factor determining commodities prices. In turn, commodities prices have a significant impact on economic health and GDP in the emerging market economies, including Turkey, since their GDP comes mostly from commodity-related activity, the main export sectors for Turkey being gold, iron, wheat flour and citrus fruits. Being the major exporter in these markets, Turkey supplies these commodities and thus affects the overall price formation in the global markets.

Tightening monetary policy and the resulting higher funding costs will likely contribute to the increase in the prices of commodities in which Turkey has a significant market share, driving down supply in the short-term. Nevertheless, if steady and stable growth of the economy is achieved, driving investment inflow into the country, this will bring more favourable conditions in the medium term, providing stable supply and exerting downward pressure on commodity prices.

0 Comments