Introduction

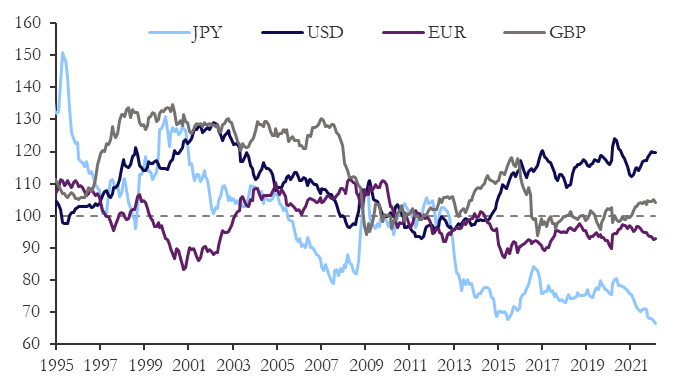

Recent data on the USD/JPY pair showed a significant strengthening of the US dollar against the Japanese currency, reaching an all-time high since 2016, marking almost a 5% decline YTD. This piece of news, however, is only the most recent episode of a significant weakening streak in the Yen’s value, not only in nominal but also in real effective exchange rate (REER) terms. The REER represents a currency’s value with respect to a weighted basket of the economy’s trading partners, adjusted by the respective price levels. The chart below shows the REER of the G4 currencies. On this metric, the Yen reached a 50-year low, the lowest level since the end of the Bretton Woods agreements. The reasons behind this trend are to be found in the last decades of the country’s economic history, as well as a significant divergence in monetary policy between the Bank of Japan and the Federal Reserve. Additionally, due to the Yen’s reputation as a “safe haven” one should expect the currency to appreciate amidst the recent economic and political uncertainties. On the contrary, over the last months, the currency has continued its depreciation against its European and American counterparts, triggering further uncertainty on forex markets.

Figure 1: Real Equilibrium Exchange Rate (Indexed at 2010) (Source: BIS)

In this article we analyse the fundamental factors that led to the Yen’s continued weakness, delving into the reasons of the Japanese crisis and try to shed light on its surprising development in the last weeks. The article concludes by providing brief guidance on the main factors that could drive the Yen’s future performance.

A Troublesome History

After the second World War, Japan started its development towards becoming an industrial and manufacturing economy. This caused a continuous appreciation of the Yen throughout the 70s and 80s, as the increase in returns of Japanese assets lead to substantial foreign capital inflows and spurred speculation. However, this boom was put to a halt with the adoption of the Plaza Accords of 1985. It set out the target of depreciating the US dollar against several international currencies (among those the Yen) and thereby initiated a severe recession in the subsequent years. The currency sharply appreciated from 250 Yen per USD up to 160 per USD, reaching a record breaking 120 Yen per USD in 1988. Such a quick and substantial increase eroded the Japanese exports, which constituted a substantial part of the country’s economy given its trade surplus. The crisis, known as “Endaka Recession”, would later cause the Bank of Japan to engage in aggressive monetary easing in an effort to prevent the currency from appreciating even further, again fuelling investments flows and, thereby, the whole economy.

But also this period of strong economic growth abruptly ended after the collapse of asset and real estate prices in the early 1990s. The complex dynamics of the crisis led to a turning point in the history of the country, as Japan would never experience sustained economic growth ever since. Indeed, following the “bubble burst” in 1991, Japan suffered from a prolonged recession, which is commonly referred to as the “lost decade(s)”. The growth rate of the economy never recovered and hovered around zero for the majority of the 1990s as well as early 2000s.

The impact of the Great Recession further aggravated the situation and caused the Japanese economy to stagnate completely. In the following years, the BOJ engaged in a prolonged monetary easing to boost the growth rate. Together with the adopted expansionary fiscal policy and structural reforms to encourage foreign investments, this set of measure is commonly labelled “Abenomics”. In the years following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), they led to a substantial weakening of the Yen against its major trading partners and are in effect until today.

Yet another important driver of the structural weakness of the Yen has to do with the sluggish Japanese productivity. Across the G7 countries, Japan reports the lowest productivity, with per-hour and per-capita figures just at 60% the level of the US and ranking 21st among the 36 OCSE nations.

Figure 2: G7 Nations per-hour Labor Productivity

This negative performance started right after the 1990s crisis, with several major manufacturing players building factories in the US and Europe or investing in Asian countries with cheaper labour. Such a fierce competition during an economic crisis drove away most of foreign investments, not only triggering a vicious cycle of recession causing deflationary pressure on the country, but also drastically reducing demand for Yen and leading to the currency depreciation.

On top of this, demographical trends did not play in favour of Japanese productivity figures, with the oldest average population among the developed countries and a shrinking working force. This negative shock on productivity has also a direct effect on nominal exchange rates of the Yen as it influences the currency value in real terms. We can explain this link in REER terms with the Balassa-Samuelson effect: according to this theory productivity differences are responsible for systematic deviations in prices and wages, as well as GDP expressed in exchange rates and Purchasing Power Parity (PPP).

In brief, since the prices of tradable goods need to be equal across countries, a higher productivity in countries with trade surpluses means that real wages will increase, and this will bring up prices of non-tradable goods and services as well. Clearly, the opposite effect, just like in Japan’s instance, is also true: a stagnating tradable sector has narrowed the previously relevant gap between the latter and the non-tradable one, with a consequent real wage decline.

Figure 3: Japanese Real Wage Index

Recent Macroeconomic Developments

The weakness of the Yen, however, cannot not be entirely attributed to historical reasons and long-run trends. As holds true for most asset classes, monetary policy has been an important factor over the last several months and years. The significant divergence between the BOJ and other major central banks, such as the Fed or the Bank of England, has to be highlighted in this regard. Indeed, as most major economies fight persistently high inflation levels, central banks have started their tightening policy by reducing asset purchases and increasing interest rates. In Japan on the other hand, inflation and growth remains sluggish partially due to the factors described above. The BOJ therefore holds on to its dovish position, which in combination with the continuing fiscal stimulus further contributes to the depreciation of the Yen.

Besides monetary policy, the substantial spike in energy prices caused by the geopolitical tension in Ukraine was a key headline in the first quarter of the year. Although Japan consistently posted an annual current account surplus during the last four decades, its economy is heavily reliant on energy imports. In January, the spike in commodity prices led to the second monthly largest current account deficit since 1985. As long as energy prices remain on an elevated level, additional downward pressure on the Yen can be expected to persistent as importers are required to sell more Yen to satisfy their needs.

Revisiting the Yen’s Safe-Haven Characteristic

Nevertheless, this one factor seems insufficient to explain the Yen’s more recent weakness its established reputation as a safe haven during market turmoil. Assets are usually labelled as safe havens if they appreciate in times of economic or political uncertainty. On the contrary, in the first week of Russia’s invasion, the Yen depreciated more than 5% against the US dollar and more than 3% against the Euro. Although the definition of safe havens seems straightforward, the channels by which the appreciations are driven are often obscure. In the following we analyse potential mechanisms that could explain the Yen’s historical strength when volatility increases to investigate whether they are still functional.

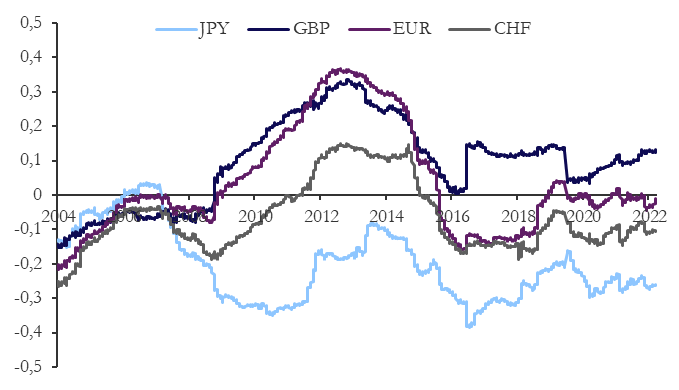

The Yen’s reputation as a reliable source of positive returns in times of crises was coined during the mid-2000s. The chart below shows the three-year rolling correlation between daily returns in the VIX and the USD exchange rate for the most liquidly traded currency pairs. All exchange rates are denoted with USD as base currency, meaning that an increase in the exchange rate is equivalent to an appreciation of the dollar. A negative correlation between VIX and exchange rate returns could therefore be interpreted as “safe haven behaviour”.

Figure 4: 3y Rolling Correlation between VIX and Exchange Rate Returns (Source: Yahoo Finance)

Since the onset of the GFC, the Yen seems to consistently benefit from market uncertainties. Up until today, the returns of the USDJPY pair are negatively correlated to movements in the VIX and this correlation is substantially below the one of all other exchange rates. It should be noted at this point that the US dollar itself is an established safe-haven currency. While it would therefore be possible that an appreciation of both currencies with regards to the rest of the world cancelled out in the bilateral exchange rate, the persistence of the negative correlation is a sign of the Yen’s strong ability to protect investors from market turmoil in the past.

As the chart above considers three years of data, it is not fully informative about more recent development in the Yen’s behaviour. To understand its more recent sluggishness, it is worthwhile to first revisit the driver’s behind the safe-haven characteristic. Two factors are commonly referenced in this regard. First, the unwinding of short Yen positions that were built-up during calmer market condition as part of carry trades. Second, Japan’s position as biggest net creditor in the world, supposedly leading to capital inflows in times of crises.

Carry Trades and their impact on the Yen

Carry trades are among the most commonly employed strategies in FX markets. They aim at generating constant positive returns by exploiting interest differentials between two currency areas. This is achieved by borrowing money in a low-interest environment and investing the raised cash in a higher yielding market. As these trades are usually highly leveraged, movements in the spot exchange rate, specifically an appreciation of the borrowing currency, can lead to substantial losses. An earlier article outlining the functioning of carry trades, including a trade idea for the USD/CHF pair can also be found here.

Especially in the run-up to the GFC, the Yen was the borrowing currency of choice due to the BOJ’s accommodative monetary policy following the burst of the asset and housing price bubble in the early 1990s. This led to a substantial interest rate differential with other developed economies. Together with a bounded volatility of exchange rates, this factor made the Yen carry trade an attractive investment strategy. The Australian dollar (AUD) and the New Zealand dollar (NZD) were commonly used as investing currencies due to their offered interest rates, while also providing high levels of liquidity, allowing traders to close their positions without incurring substantial costs. This led to the build-up of substantial short positions in the Yen that were unwound during the onset of the GFC, leading to a substantial appreciation of the Yen. The chart below shows the exchange rate of the Yen, as well as the difference of the 3-month interbank interest rates vis-à-vis these two currencies.

Figure 5: Attractiveness of the Yen Carry Trade against AUD and NZD (Source: Yahoo Finance, FRED)

The charts display the strong appreciation of the Yen against both currencies during the GFC that was triggered by the closing of sizable Yen positions. Further, the time series displays the substantial loss in attractiveness of both Yen carry trades, especially since the beginning of the Covid pandemic. As central banks of investing currencies adopted an extremely accommodative stance, interest rate differentials and thereby the expected profitability of carry trades fell. Moreover, this policy synchronisation further undermined the Yen’s exceptional position as leading borrowing currency by making short positions in USD or EUR equivalently attractive. Taken together, both factors (reduced profitability of Yen carry and rise of other borrowing currencies) can be seen as causes for the diminished impact of economic uncertainty on the Yen during the most recent months.

Investor Positioning and Market Psychology

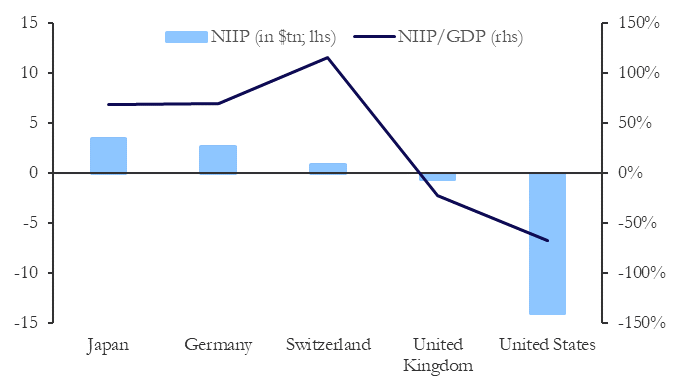

A second commonly referenced factor for the Yen’s safe-haven property is Japan’s positive net international investment position (NIIP). The NIIP is defined as the difference between a country’s foreign assets minus domestic assets controlled by foreigners. Its most relevant sub-categories are equity, debt, FDI, and derivatives. Put simply, the statistic measures whether domestic investors deployed more capital abroad than flowed into the country by foreign investors. As can be seen from the chart below, Japan is the biggest net creditor in the world in absolute terms.

Figure 6: Comparison of Net International Investment Position (Sources: IMF, FRED)

It is commonly argued that Japanese investors partially repatriate these foreign investments during times of increased volatility. These capital inflows then lead to an increase in the demand for Yen and therefore an appreciation of the currency. While this story sounds plausible, empirical evidence to support the argument is scarce. As a matter of fact, research on capital flows during the GFC provides strong evidence that Japanese investors even increased their foreign exposure. [5] This fact makes the risk-averse behaviour of Japanese investors an unlikely cause of the Yen’s safe-haven property.

Besides these factors that go back to investor positioning, one should not disregard market psychology in analysing the Yen’s behaviour during market turmoil. It appears plausible that e.g. companies with foreign subsidiaries increase their hedging activities when uncertainty rises as they expect the Yen to appreciate based on their experiences from earlier crisis episodes. Similarly, traders could ramp up their long exposure on the currency when they expect the safe-haven property to hold. The appreciation of the Yen would then realize as part of a self-fulfilling prophecy. While it is inherently difficult to prove its existence, research indicates that such a channel at least contributes to movements in the exchange rate. [6]

Given its weak performance during the onset of the Covid pandemic, the Yen’s supposedly incontestable status as safe-haven currency is substantially called into question. This fact by itself might therefore explain its more recent sluggishness amidst Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And also during future economic downturns, traders and hedgers might have to think twice before taking action, thereby further undermining the Yen’s ability to provide countercyclical returns.

Conclusion

In this article we presented fundamental and macroeconomic factors that are key to understanding the Yen’s weakness in the medium to long term. The economy’s sluggish growth, entrenched deflationary factors, and low levels of labour productivity are likely to continue to act as a downward weight on the Yen in the near future. Additionally, the arising divergence in monetary policy stance between Japan and other major economies could well reinforce this development.

Turning to the Yen’s historic ability to protect investors in times of market stress, we investigated factors that could explain its surprisingly weak performance amidst the Ukraine conflict. It is apparent that the diminished attractiveness of the Yen carry trade could play a significant role in this regard. While it could regain some of its momentum due to the described divergence in monetary policy, the initial borrowing phase of the trade is likely to put the Yen further under pressure.

References

[1] OECD, Economic Survey of Japan, 2021

[2] Takatoshi Ito, Why Is Japan So Cheap?, 2002

[3] Takako Gakuto, Takumi Tamura and Daisuke Nakamoto, No longer a safe haven, once-mighty yen slumps, 2022

[4] Anna Hirtenstein, Falling Dollar Shows Resurgence of Infamous Carry Trade, 2021

[5] Andreas Steno Larsen and Santeri Niemelä , Killing a darling: Japanese investors don’t sell foreign assets during turmoil! Is the JPY safe haven status justified?, 2020

[6] Dennis Botman, Irineu de Carvalho Filho, and W. Raphael Lam, The Curious Case of the Yen as a Safe Haven Currency: A Forensic Analysis, 2013

1 Comment

Marco Macro · 29 March 2022 at 13:37

Short non fx hedged nky at current levels?