Two days ago, during its regular policy meeting, the ECB left interest rates unchanged and Mario Draghi said the “council was comfortable acting next time.” He signaled that there was a unanimous belief that the current inflation rate of 0.7% is unacceptable. He also stated that the strength of the euro was a “serious concern” for the European economies. As he gave his speech, the euro retreated from almost $1.4 to $1.3858, a fall of 0.4%. But what has caused this strengthening of the euro, which first started in August 2012?

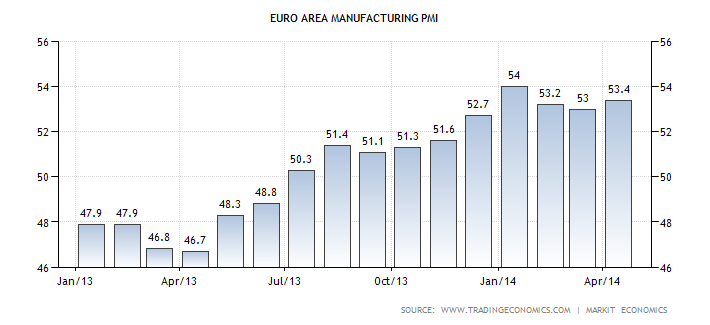

Well, we believe many different factors are at play here. One factor might be the euro area manufacturing expansion, as measured by the Euro Area Manufacturing PMI, which hit 50.3 in August 2013. Numbers above 50 signal expansion. This renewed confidence in European manufacturing might have at least partially buoyed the euro. This confidence has also helped European stocks. Another strong factor is the Euro Area current-account surplus, which now sits at about 2.5% of GDP.

Source: TradingEconomics, Markit Economics

Source: TradingEconomics, Stoxx

However, we believe monetary factors are the strongest ones until now. The weaker than expected US recovery has slowed expectations of short-term hikes in American interest rates, therefore keeping the dollar weaker. In the US, although there is a tapering going on, the Fed is still increasing liquidity in the system, currently at a rate of $45 billion per month ($20 billion in agency mortgage-backed securities and $25 billion in long-term Treasury bonds). The 10-year US treasury yield is at 2.61%, lower than the 3% level it hit in January 2014, when the markets expected a stronger US recovery. The weaker US growth prospects have reflected themselves in the TIPS markets as well. A frequent measure of US expected inflation, the difference between the yields in US Treasury bonds and TIPS, fell from 2.4% in January 2014 to 2.2% in May 2014. These lower expectations have kept the dollar weaker. An additional reason for the euro’s strength is the Ukraine-Russia conflict. According to Mario Draghi himself, the conflict has caused about €160 billion of capital outflows from Russia. Part of this capital entered European financial markets, probably buoying the euro further.

Source: TradingEconomics, OTC Interbank

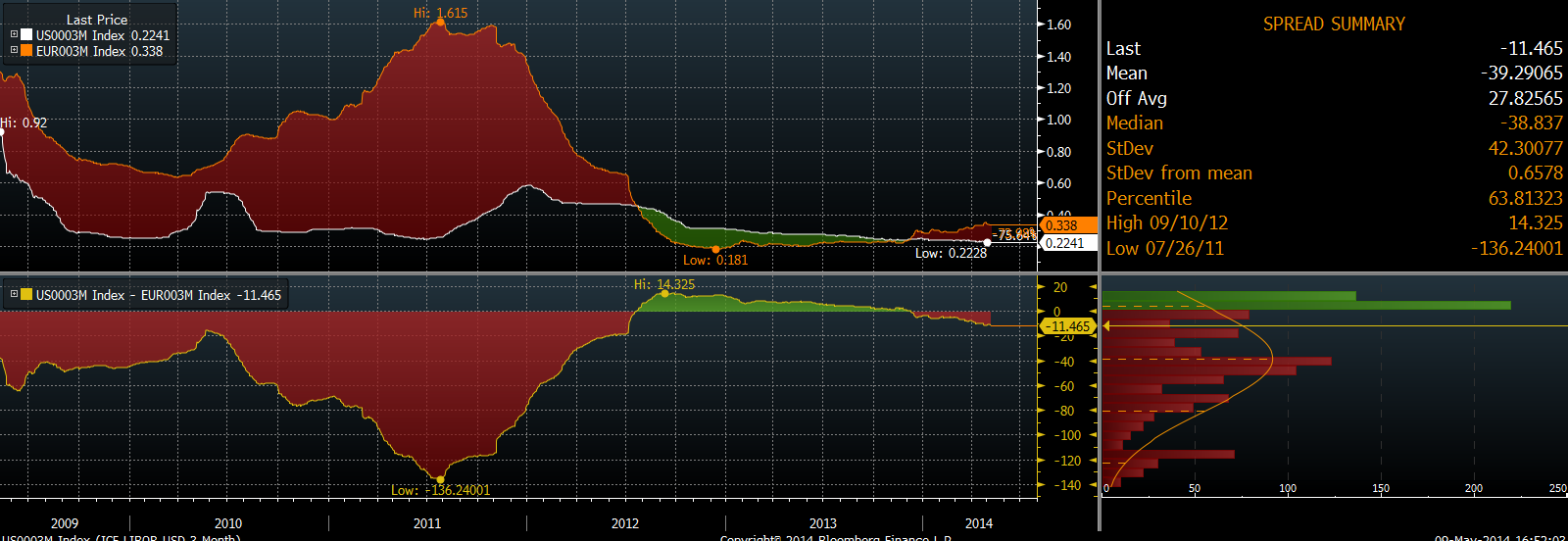

With a large number of European banks prepaying the loans they had gotten using the LTRO schemes, there has been a surge in the EURIBOR rate. The 3-month EURIBOR rate currently stands at 0.338%, whereas the LIBOR rate is currently 0.22%. These repayments have caused a credit tightening at an uncomfortable time, as shown by the higher EURIBOR rate, and have accounted for a shrinkage of the ECB balance sheet.

Source: Bloomberg

So what should the ECB do?

Well, with the inflation rate constantly falling, the ECB is faced with many difficult challenges. On one hand, it wants to avoid having to do deep Quantitative Easing and is hoping that a possible negative-deposit rate will do the job of weakening the euro and stimulating lending, and on the other hand it wants to immediately weaken the euro (which might need to involve QE), which, being as strong as it is, has lowered the price of imports and has actually caused a downward pressure on inflation (since the prices of many imports enter the price index).

Source: TradingEconomics, Eurostat

The first alternative the ECB is facing is lowering the deposit rate into negative territory, which would basically mean banks get penalized for keeping overnight funds at the ECB. There has already been a precedent, with the Swedish central bank lowering the deposit rate to -0.25% to fight the economic slowdown in 2009. However, the results in Sweden were disappointing: the reform failed to increase credit and did not seem to yield any observable benefit. Consequently, the policy was soon reversed. The same thing may happen in Europe as well. The threat of negative deposit rates could be one that market participants do not take so seriously, as shown by the continued strength of the euro despite multiple threats by Draghi to do just so.

The second alternative the ECB is facing is deep-down Quantitative Easing. This alternative was more prominent in the news a few months ago, whereas now markets seem to have priced in the possibility of no quantitative easing, as the strong euro suggests. Many economists and market participants believe full-blown QE would be the only way to save Europe. But what kind of QE? Most people believe new and more innovative lending schemes are needed. So, if the ECB finally decided to go with QE, it would have to include heavy purchases of private assets, such as asset-backed securities. But markets for these securities are very underdeveloped, especially in the peripheral economies, so the ECB’s task and priority would have to be creating new schemes for SIVs and other vehicles to start pooling private assets which could perhaps affect the economies more deeply than simple government-bond purchases. However, this takes time. The point to remember is that Draghi saved the euro by threatening to do “whatever it takes.” Perhaps, with the still-strong euro at the moment, the markets are becoming a bit impatient and Draghi’s credibility is being tested.

Purchasing power analysis suggests that the euro is too strong for the peripheral nations. Regarding Greece, Spain and Italy, for example, the exchange rate would have to be close to $1.11 per euro (€0.90 per $ in the axis below).

By PPP analysis, therefore, the euro is being priced as a Deutsche mark, effectively having the “correct” purchasing power a deutsche mark would have today in Germany. This would suggest that wage cuts and therefore price deflation are necessary in the peripheral economies for the competitiveness of these nations to be restored, whereas price inflation is needed in stronger economies such as Germany. However, this does not seem to be the goal of the governments, nor the “lobbying” task of the ECB.

Therefore, the only way to fight these asymmetries between European nations would be to have a heavy depreciation of the euro, close to the levels suggested by PPP. However, we believe that this heavy depreciation can only be achieved through a massive-scale quantitative easing program and not by empty threats aimed at shifting expectations.

Sources:

o http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20140430a.htm

o http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/450424ec-d77f-11e3-80e0-00144feabdc0.html

o http://danskeresearch.danskebank.com/abo/NegativeratesinDKNovember2013/$file/Negative_rates_in_DK_November_2013.pdf

o http://www.wiwi.uni-muenster.de/cawm/forschen/Download/Diskbeitraege/DP43_IlgmannMenner.pdf

[edmc id=1673]Download as pdf[/edmc]

0 Comments