Introduction

The introduction of the common currency started a landmark European integration process. However, the sovereign debt crisis showed all the limits of an incomplete European integration, limited to monetary policy only, with a single central bank and 19 independent debt markets.

The sovereign debt crisis was exacerbated by a vicious relationship between peripheral Europe government and their weak banking system, known as sovereign debt diabolic loop. The loop works as follows. Whenever a negative shock affects investors’ expectations regarding sovereign risk, domestic banks suffer. Domestic banks, in fact, are overexposed to domestic debt and, as domestic bonds sell-off on the back of the negative shock, so the banks’ capital shrinks due to the reduced marked-to-market value of their bond holdings. The increased bank leverage poses serious risks to the solvency of the bank, increasing the likelihood of a government bailing-out. In fact, governments are unable to commit ex-ante not to bail-out banks due to the high political risks at stake. Moreover, banks attempt to decrease their leverage by cutting loan origination. The following credit crunch hurts the real economy and could trigger a recession. The increased likelihood of government bail-outs and the negative spillover of credit crunch on the real economy increases investors’ concern on the sovereign creditworthiness. This affects the banking sector and so on.

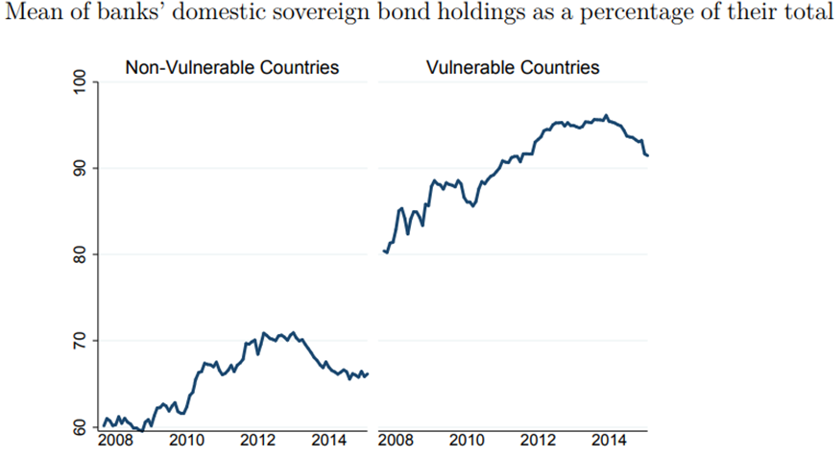

The sovereign debt diabolic loop lies on bank’s home bias. Despite the availability of many euro-denominated sovereign bonds, banks are overexposed to domestic debt. A possible explanation addresses to Basel III capital regulations, as the risk weights on exposures to domestic sovereign debt are set at zero. This approach is totally inconsistent with the evidence that different European countries carry a different credit risk. It is interesting to notice that the home bias seems to increase during crisis, thus magnifying the effect of the diabolic loop.

Chart 1: Mean of banks’ domestic sovereign bond holdings as a percentage of their total assets (Source: ESBies: Safety in the Tranches – European Systemic Risk Board)

This behaviour reflects two distorted incentives. The first is the gamble-to-resurrection stance of banks on the verge of default. These banks attempt to earn the credit spread by investing in their domestic risky sovereign bonds. The second is a moral-suasion stance adopted by domestic publicly-owned banks and recently bailed-out banks.

In order to break the diabolic loop, tighter capital requirements were introduced. Moreover, the European Stability Mechanism and the Single Supervisory Mechanism were created. Many analysts agree that these solutions are incomplete because they do not address to the fundamental problem of the home bias. Banks could overcome the home bias only if a European risk-free asset existed, as they could store value in the risk-free asset rather than in the risky sovereign bonds of the country in which they reside.

We can define a risk-free asset as an asset that stores value without being exposed to default risk. Therefore, an asset to be categorized as a risk-free asset should be liquid, maintain value in crises periods and be denominated in a currency with stable purchasing power. The world most popular risk-free assets are US Treasuries. In Europe, German Bunds are traditionally regarded as risk-free given the solidity of the German economy and the acknowledged fiscal discipline of the German government. Beyond Germany, the other euro-area triple-A countries are Luxemburg and Netherlands. One could point out that the universally accepted risk-free Treasuries are issued by a non triple-A country. In fact, Stadard and Poor’s downgraded US debt to AA+ in 2013. The euro-zone countries with AA+ debt are Austria and Finland. Even considering the enlarged group of safe euro-zone debt, we realize that the euro area does not supply a safe asset on a par with US Treasuries if we consider the size of the European and US economies. In fact, dollar-denominated risk-free assets are abundant relative to the size of the US economy: government gross debt of the United States stood at $19.7tn in 2016, equal to 106.1% of US GDP. On the other hand, the joint government gross debt of Germany, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Finland and Austria stood at $3.34tn in 2016, equal to only 28% of the euro area GDP. As we can see, in the euro area there is a pronounced asymmetry in the supply of risk-free bonds, with Germany supplying 71% of the risk-free euro-denominated sovereign debt.

Following the European sovereign debt crisis, many proposals have been raised to consolidate and mutualise the European sovereign debt, and a vast debate arose on the topic. Two main principles underlie the views of those in favour and contrary to the proposals, respectively. The first one is the principle of solidarity, according to which stronger economies should help and support weaker ones, especially in times of crisis. On the other hand, the principle of accountability demands that each country is responsible for its own debt and fiscal decisions. In the following paragraphs, we will review some of the most popular proposals, and investigate whether they could help in creating the aforementioned “European risk-free asset”, with a particular focus on European Safe Bonds.

Blue bonds

In May 2010, Jakob von Weizsäcker and Jacques Delpla published a proposal for the mutualisation of European sovereign debt. According to them, European countries should pool together up to 60% of GDP of national debt under joint liability (blue bonds), and leaving the eventual remaining debt as liabilities of the single countries (red bonds). Four beneficial effects would arise from this situation. First, the blue bonds would constitute the European risk-free asset discussed above. Second, the interest costs of blue bonds would be lower than those bore by the majority of countries. Third, the marginal cost of (subordinated) red bonds will increase, thus giving an additional incentive for fiscal adjustment to countries with high debt. Finally, smaller countries with illiquid bonds would benefit from the extra liquidity of blue bonds.

Stability bonds

In November 2011, in the middle of the sovereign debt crisis, the European Commission published a green paper “on the feasibility of introducing Stability Bonds”. The commission proposed three different options for the joint emission of debt from European countries:

Full substitution. According to this approach, the entire sovereign debts would be substituted by a common issuance, with joint guarantee. This option was however, even for the Commission, too ambitious to be put in practice. A major problem arising from this approach is the high risk of moral hazard: undisciplined countries could continue to spend more than they could afford, at the expense of more disciplined countries.

Partial substitution with joint guarantee. In this case, stability bonds would only cover a part of national debts, and the rest would be borne by the individual countries. This option is very similar to the blue bonds proposal, and would limit the moral hazard problem.

Partial substitution with no joint guarantee. In this case, no moral hazard is feared, since the default risk is not split among countries. Also, this is the only case in which no change in the European treaties would be needed as, quoting the Commission, “the instrument seems also fully compatible with the Treaty”.

This proposal of the commission was never implemented, mainly because of the opposition of low-debt countries, such as Germany, which saw no advantages in bearing the debt -and the default risk- of higher-indebted countries. However, what is uncontroversial is that it would have provided the single risk-free asset for the Euro area.

European Redemption Pact

In the same days in which the European Commission published its green paper on stability bonds, a completely different proposal was launched by the German Council of Economic Experts: the European Redemption Pact. The council acknowledged the difficulties of peripheral countries in reducing their debt due to the high cost associated with it. But instead of proposing a mutualisation of the debt up to a certain percentage of the GDP, they suggested to share the portion exceeding it.

The idea goes like this. During the roll-in phase, all debt exceeding 60% of GDP of countries is bought by a joint European Redemption Fund, which can finance itself by issuing new bonds. These bonds, however, will have interest rates sensibly lower than those bore by single member states, as they will be jointly guaranteed. Then, the member states shall redeem their obligation to the fund according to a predetermined payment schedule, which will reflect the lower borrowing costs bore by the fund. At the same time, member states must commit not to increase the individual debt above the threshold of 60% again. The took the case of Italy as an example, and they found that, if the redemption period lasts 25 years, assuming a nominal growth rate of 3% and financing costs of 4% for the fund and 5% for the remaining debt (the 60% of GPD portion), Italy would need a primary surplus of 4.2% of GDP for each year to comply with the repayments. Albeit quite high, this is quite lower than the calculated 6.8% that is needed without the ERP.

This proposal does not directly create a single risk-free asset, as the ERP is set to be limited in time, but under the assumption that at the end of the program all countries keep a debt-to-GDP not higher than 60%, we can easily assume that most, if not all, of the individual sovereign bonds could be treated as risk-free.

European Safe Bonds

An additional possible solution to the lack of financial integration would be the introduction of European Safe Bonds (ESBies) first theorized by Brunnermeier in 2011. In the ESBies framework, a supranational entity would buy a diversified portfolio of euro-area sovereign bonds and issue asset backed securities split in two tranches. European Safe Bonds (ESBies) are the senior tranche while European Junior Bonds (EJBies) are the subordinated tranche. In this scheme, losses arising from sovereign defaults would first be borne by holders of junior bonds and only when all EJBies are entirely wiped out, would ESBies begin to take any losses. Thanks to their senior status and the high level of diversification, ESBies would become the euro-denominated risk-free asset. This way ESBies would allow to break the sovereign debt diabolic loop. Moreover, ESBies are superior to the other solutions mentioned. In fact, unlike blue bonds, stability bonds and the European Redemption Pact, ESBies do not require changes to EU treaties and do not entail joint and several liabilities of debt among governments, thus avoiding moral hazard and preserving the principle of fiscal discipline.

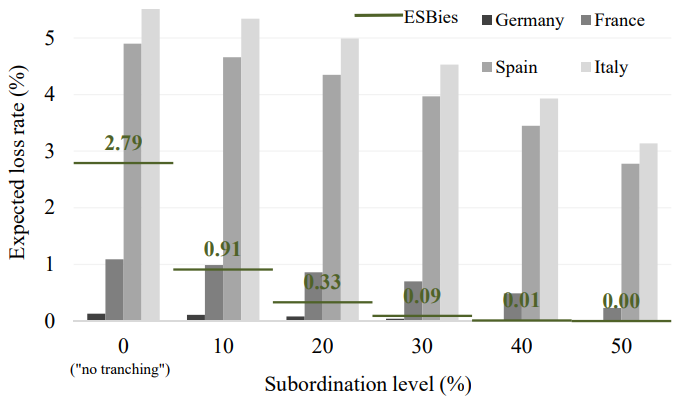

A key variable in the construction of ESBies is the subordination level, i.e. the portion of junior tranches over the total notional. When setting the subordination level, the ESB-issuer faces a trade-off. The higher the subordination level, the more creditworthy the ESBies, as a larger amount of sovereign debt has to default before losses hit the senior tranche. On the other hand, a high subordination level entails that only a small share of ABSs are ESBies, thus decreasing the supply of safe asset. This is a key point because one of the problematic aspects of the status quo we pointed out above is the relatively low supply of euro-denominated risk-free debt.

In its work, Brunnermeier uses a subordination level of 30%, meaning that out of 100 of notional, 30 is represented by EJBies and 70 by ESBies. The 30% subordination level is deemed a reasonable middle-ground between minimizing credit risk and maximizing risk-free asset supply. According to Brunnermeier, with this configuration, ESBies would supply 40% more risk-free assets than German Bunds do and entail an expected loss rate of 0.09%. This is lower than the expected loss rate of 0.20% implied by German CDS, estimated by Deutsche Bank in 2015. It is important to highlight that the two figures are not perfectly comparable. In fact, counterparty credit risk and liquidity premia inflate CDS spreads, while these two factors are not considered in Brunnermeier simulation as ESBies have no counterparty risk and they are expected to be very liquid assets, given their risk-free characteristics.

The result of Brunnermeier simulation connecting the assets’ expected loss rate and the subordination level are plotted in the chart below.

Chart 2 (Source: ESBies: Safety in the Tranches – European Systemic Risk Board)

The no tranching state refers to the limit case of a diversified portfolio of euro-area sovereign bonds with no subordinate debt. In other words, in the no tranching state EJBies do not exist and all bonds are ESBies. As the subordination level increases, the expected loss rate decreases as we expected. When the subordination level is 50%, the credit risk of ESBies is virtually null. The vertical bars in the chart show the expected loss rates of blue bonds in a blue-red bonds framework. As one would expect, the expected loss rates of blue bonds decrease as the subordination level increases. If we want to compare ESBies and blue bonds, we should recall that the subordination level in the blue-red bonds framework is not fixed but it changes from country to country. In fact, the share of red bonds is determined as the share of sovereign debt exceeding 60% of the national GDP. Therefore, the higher the national debt-to-GDP ratio, the higher the share of red bonds, the higher the subordination level. Considering 2016 debt-to-GDP ratios for the four countries listed in the chart (the euro-area countries with the largest gross sovereign debt), the subordination level would be 12% for Germany, 38% for France, 40% for Spain and 55% for Italy. The no tranching state reports the expected loss rates of the national bonds. In fact, in the no tranching state, there are not national subordinate bonds (i.e. red bonds) and so blue bonds correspond to the outstanding bonds. The chart confirms Brunnermeier conclusion according to which, at a 30% subordination level, ESBies would entail an expected loss rate slightly lower than that of today’s German Bunds. This result is accomplished thanks to diversification and the loss-absorption buffer provided by EJBies.

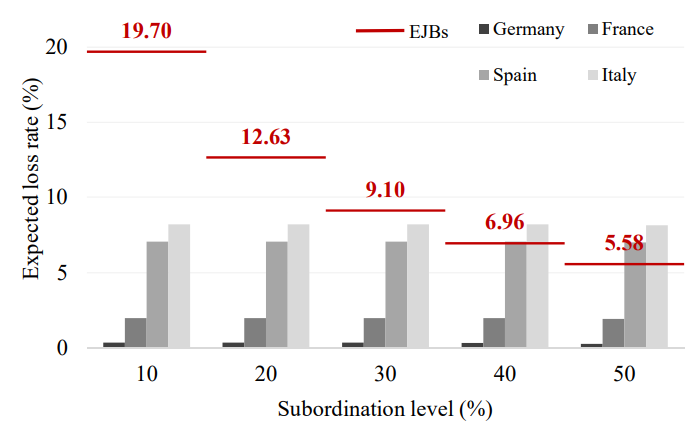

Brunnermeier replicates the analysis on the expected loss rate on EJBies too. The results are plotted in the following chart.

Chart 3 (Source: ESBies: Safety in the Tranches – European Systemic Risk Board)

As we can see, at a 30% subordination level, the expected loss rate is 9.10%. The weighted average expected loss rate of the four lowest rated euro-area countries (Italy, Portugal, Cyprus, and Greece) is 9.32%. According to this data, the concern that no investor would buy EJBies is misplaced. As investors hold Italian public debt (notional value of €2.28tn), then they would hold EJBies too. According to Brunnermeier, the forecasted notional value of EJBies at 30% subordination level is €1.82tn.

Disadvantages of ESBies

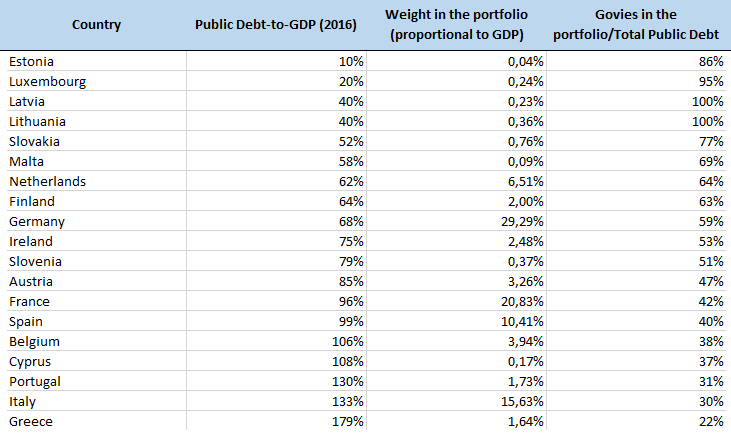

A fundamental issue regards how to compute the weight of sovereign debt in the diversified portfolio of euro-area sovereign bonds from which ESBies are created. As ESBies would be the risk-free asset of the euro area, portfolio weights should be set according to country relative contribution to euro-area GDP. This weighting system poses a serious problem, due to the differences in debt-to-GDP ratios across European countries. The implementation of ESBies would create a residuals’ issue in the euro area. As the chart below shows, the debt of countries with a low debt-to-GDP ratio (such as Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) will be bought almost entirely by the ESB-issuer, resulting in a very thin market for residual securities and huge price distortions due to low market liquidity. On the other hand, the ESB-issuer would buy only a small portion of the debt of countries with a high debt-to-GDP ratio (such as Italy, Greece and Portugal but also Belgium and France).

Table 1 (Source of Public Dept-to-GDP data: Trading Economics)

The net result is that the spread on the unsecuritised debt could increase due to the collapse of collateral demand by banks (now satisfied by the ESBies) and the consequent effect on market prices of the sovereign bonds. Peripheral governments would be forced to implement severe austerity measures to refinance maturing government debt.

Conclusion

As we showed, ESBies would represent an improvement by increasing the supply of euro-denominated risk-free assets. However, they do not solve the essential problem, which is that some countries in the euro area are vulnerable to sudden spikes in borrowing costs, while others are not due to the different fiscal policies implemented and the countries’ different debt burdens. From this perspective, we are in a puzzle as only risk-sharing schemes, such as the blue-red bonds and the stability bonds, could overcome this problem, though entailing joint liability and all the connected moral hazards.

0 Comments