The Emerging Markets sell-off of late January highlighted the importance of the Chinese economy in the global markets and the instability of its financial sector.

China has pulled global growth in the last decade, attracting investments, exporting goods all over the world and financing businesses and governments, especially the US. Therefore, it is straightforward to realize that a slowdown in production and investments could hamper global growth, and to understand why there has been so much talk about manufacturing PMI and real GDP growth rate since the beginning of the year.

Source: TradingEconomics, National Bureau of Statistics of China

However, the main focus of economists, and indeed of this article, is the area that has been characterizing the impressive expansion of the Chinese economy: the financial sector. The key concept in this context is definitely Shadow Banking.

Definition: Shadow Banking

According to the report released by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in November 2011, shadow banking is defined as “credit intermediation involving entities and activities outside the regular banking system”. In April 2012, former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke said: “Shadow banking, as usually defined, comprises a diverse set of institutions and markets that, collectively, carry out traditional banking functions – but do so outside, or in ways only loosely linked to, the traditional system of regulated depository institutions”.

Practically speaking, it refers to all nonbank financial institutions that are engaged in activities of maturity transformation. However, banks themselves have created vehicles to which they can transfer the same kind of activity, performing it off-balance-sheet.

Shadow banking is not a concept related to China only, but in the world’s second largest economy it acquires unique and remarkable characteristics. We can have a quick snapshot of these by analysing Wealth Management Products (WMPs). WMPs are managed by trust companies and have a huge importance in the Chinese system, since they are the main investment vehicle for both individuals and corporations. We will see:

1. how they work;

2. why they have become so predominant;

3. what are the risks for the system;

4. what is the current situation.

Nonetheless, it is important to stress that WMPs do not account for the whole spectrum of investment vehicles in shadow banking in China (in particular, see LGFVs – Local Governments Financing Vehicles).

1. WMPs: what are they?

Trust companies collect funds in the WMPs both directly and indirectly (from banks) and they then lend them to companies through the following scheme:

Source: Quartz | Ritchie King

Hence, WMPs constitute an alternative lending vehicle, which is progressively not only integrating the traditional lending scheme, but also substituting it for small-medium enterprises (SMEs) and borrowers that have no access to traditional bank financing.

In fact, they decentralize the banking system and enhance growth for SMEs and local governments. However, we must separate beneficial growth from negative one, in which Return on Capital is not sufficient to justify the riskiness of the investment (i.e: is lower that the Cost of Capital). This issue is particurly evident for local governments, which have often started projects with the sole purpose of creating jobs. The result is that WMPs ended up financing many projects of dubious quality, which are actually too risky to qualify for loans. Legit and straightforward question: what would happen if they defaulted? Stay tuned…

2. Demand and success

As previously mentioned, both investors and banks began demanding WMPs massively. Let’s see why.

WMPs allow companies and individuals to invest in products with a return higher than money market funds or certificate of deposits, at short-term maturities (usually lower than one year). It is not difficult to figure out why they immediately became popular: high yield with low (perceived) risk is an obviously attracting perspective, especially in conjunction with rates on bank deposits capped to a meagre 3% by the government. In addition, thanks to these products, investors can easily avoid restrictions on investments in home properties and the real estate markets.

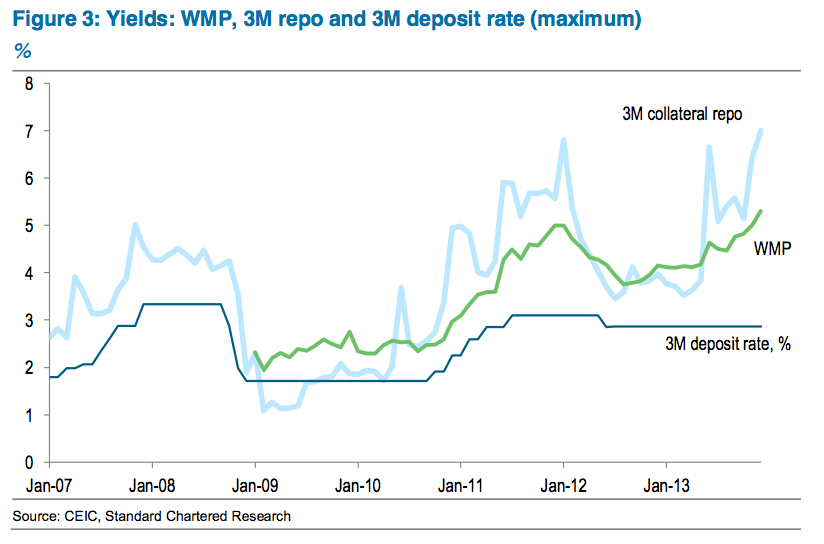

In the following picture, it is possible to appreciate how 3-month WMP yields are correlated with collateral repo yields and constantly higher than the corresponding deposit rates since 2009:

Source: CEIC, Standard Chartered Research

Banks prefer to choose WMPs instead of traditional lending due to banking regulation and credit risk. In fact, the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) for banks in China is 20%, definitely an impressive level considering that in the US is max 10% and it is not even present in the UK. Its purpose is clear: regulators wanted to avoid liquidity problems and, thus, instability of the system. However, banks started increasing their demand for the loosely regulated WMPs, which are off-balance-sheet items and do not count towards the RRR. As a consequence, banks can simply profit from these products, without having to satisfy any liquidity requirement that could hamper their profitability. Furthermore, although they control the process as a whole (origination and distribution of WMPs), neither banks nor trust companies are responsible for credit risk! In fact, with this originate-to-distribute kind of process, credit risk is directly trasfered to the investor (1). Don’t tell me that “moral hazard” came to your mind… Indeed: big incentives to disintermediation.

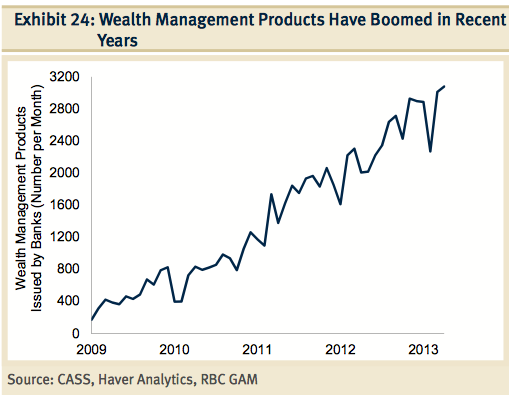

Given the heavy demand, the final outcome is striking:

Source: Quartz (qz.com), BofA/Merril Lynch

Source: CASS, Haver Analytics, RBC GAM

3. Risks and instability

What are the consequences of the extensive diffusion of WMPs?

First of all, the system is heavily exposed to default risk. As previously stated, WMPs often finance projects of poor quality (i.e: whose returns do not adequately compensate risks), which do not deserve a line of credit. We would indeed expect frequent defaults and, thus, many investors losing the capital invested. However, this has not been the case so far: until late 2013, WMPs were considered very low risk securities and no default had ever occured.

Something smells fishy here, but the vicious circle is eventually easy to figure out: given the almost non-existent regulation on WMPs, trust companies create more credit than desired by regulators, and provide liquidity to companies regardless of their credit standing. They are even used to roll over credit lines to companies in financial distress, allowing them to pay off earlier losses (and everyone is happy…or not?). At the same time, with no default taking place, depositors started to believe that these products were guaranteed by the authorities, although no statement conferming this view has ever been released by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). Therefore, looking almost default-free and returning higher yields than similar low-risk instruments (as we saw in the previous paragraph), WMPs have become the most used investment vehicles for individuals, companies and banks. This is not very far from CDOs and what happened in the financial crisis.

Other significant issues must also be considered:

• Opaqueness: the ultimate investment destination of WMPs is often untrackable!

• Real estate market: WMPs has allowed investors to go far beyond the limits imposed in real estate and private properties. Therefore, not only housing demand is strictly correlated to demand for WMPs, but many economists have alerted for a possible housing bubble taking place in China.

• Duration mismatch: this is, in our view, the most serious issue. WMPs have an average duration inferior to 1 year. Therefore, companies are constantly financing their long-term assets with short-term liabilities. The financial literature has always been wary about the consequences of maturity mismatch. The most relevant and straightforward consequence is that companies have to constantly roll-over their borrowings and, thus, are massively exposed to reinvestment risk. What would happen in case of an increase in interest rates or changes in regulation? Ask Lehman Brothers…

In this scenario, even small defaults may have a ripple effect and cause a chain of subsequent defaults, quickly undermining the whole financial system.

Quick-and-dirty summary:

Source: RBC GAM

4. China in 2014

In June and December 2013, the 7-day interbank repo rate spiked due to uncertainties in the global markets and lack of liquidity from the PBoC.

Differently from many other countries, the central bank does not employ refinancing operations for banks, but only fine tuning operations In fact, PBoC has been reluctant to provide them additional liquidity, given the excess of credit in the economy. As a consequence, uncertainties in the economy directly impacted the interbank rate, which, in both cases, was stabilized by temporary liquidity injections from PBoC.

Why is this dangerous? A rise in the interbank rate immediately made WMPs yields increase. Due to duration mismatch, companies relying on trusts were in the tough (and unexpected) situation of refinancing their debt at a prohibitive cost (in June they almost tripled!). Luckily, authorities stepped in before serious damage could be made, and WMPs yields were driven back to reasonable levels.

The situation became radically worse in January. On Friday 17th, China Credit Trust said it may not repay in full 3bn yuan (almost $500m) of a WMP maturing on January 30th and issued through the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the world’s largest bank by assets. On January 20th, the interbank rate spiked and ICBC stated that they would not take full responsibility for the default. Te government ended up bailing out investors and, with them, the shadow banking system. However, woes and fear ushered in more than two weeks of negative returns in stock indexes around the world, with investors buying safe heavens such as Yen, German bund and US Treasury.

The big surprise came in early March: the first bond default from a Chinese corporation. On the 7th, Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy Science & Technology Co. paid just 4 million of an 89.8 million yuan coupon payment. Many expected turmoil in the whole financial sector, but, actually, there was nearly no reaction on WMP markets. Instead, government stated defaults may be positive for the markets as they would allow investors to assess the risks embedded in their investments and improve the pricing of these products. A side, but not negligible effect is the increase in demand for local governments financing vehicles (LGFVs), which are now perceived as more likely to spark a government bail-out and consequently safer than WMPs.

Finally, the bank run started on Monday 24th, although relative to a small, rural bank, highlights the uncertainties faced by depositors and investors, casting doubts on the stability of WMPs’ demand.

Conclusions

Shadow banking is inseparable from the Chinese financial system, with the government constantly trying to keep it under control through political reforms, fiscal and monetary policy. Nevertheless, credit, real estate markets and LGFVs keep on booming, as well as total debt in the economy. Allowing for defaults would improve securities pricing and convince investors that shadow investment vehicles can be expected to default.

However, we believe that moral hazard is real and unavoidable: defaults cannot be controlled forever and structural problems in the financial system will eventualy emerge from their shadows. The Bear Sterns moment has not come yet, but let us brace ourselves.

(1) In the US, securitized products were partially backed by banks: they used to inject subordinated capital into the vehicle, in order to protect investors from small losses. This does not happen in China!

Sources:

• http://www.bbvaresearch.com/KETD/fbin/mult/111123_ChinaBankingWatch_En_tcm348-280630.pdf?ts=1822013

• http://qz.com/175590/five-charts-to-explain-chinas-shadow-banking-system-and-how-it-could-make-a-slowdown-even-uglier/

• https://us.rbcgam.com/resources/docs/pdf/whitepapers/RBC_GAM-Economic_Compass-China_Credit.pdf

• http://www.peri.umass.edu/fileadmin/pdf/working_papers/working_papers_301-350/WP334.pdf

• http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2013/06/basics.htm

[edmc id=1620]Download as pdf[/edmc]

1 Comment

MARKET RECAP 29|03|14 : BSIC | Bocconi Students Investment Club · 29 March 2014 at 12:51

[…] are bearing much more risk than they actually show. (Don’t forget to read our special report on Shadow Banking in China, which comprehensively addresses this issue!) Jiangsu Sheyang Rural Commercial Bank was the most […]